A4.3.1 - A4.3.10

A4.3.1 Workshop or circle of Frans Hals, possibly Pieter Soutman, Portrait of a woman, c. 1625

Oil on canvas, 116 x 87 cm

England, private collection

This portrait displays an overall slightly smoother manner than Hals’s typical portrait type. Nevertheless, the way of lighting the hands and face is close to Hals, as well as the highlighted edges on the folds of the dress and the diagonal brushstrokes laid over the lit areas of the hands. There is, however, nothing of his typical loose brushwork visible in the sitter’s unmoving facial features. The portrait lacks the characteristic presence of Hals’s faces, and the spontaneity of actively turning towards the viewer, which can even be observed in the early portraits. The present painting is relatively close to the Portrait of a woman holding a glove by Pieter Soutman (c.1593/1601-1657) [1].

A4.3.1

1

Pieter Soutman

Portrait of a woman holding a glove, c. 1625-1630

The Hague, Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis, inv./cat.nr. 755

A4.3.2 Workshop of Frans Hals, Portrait of a man with a book, 1633

Oil on canvas, 102.9 x 88.9 cm, inscribed and dated upper right: ÆTAT SVÆ 73 / AN° 1633

Tokyo, Fuji Art Museum, inv. no. 1235

This portrait’s sitter is either a priest or a scholar. His stiff posture and rigid hands, especially the one resting on the book, differ from Hals’s usually foreshortened hand and arm positions which are usually captured in motion. There is also no coherent planar composition that establishes a visual connection between the areas of hand and arm, and the contours of the face. The restless rendering of the facial features, hair, and beard, which disintegrates into many short brushstrokes, was certainly not done by the Hals himself, but by an assistant. The latter imitated Hals’s brushwork without achieving the master’s concentration on a few significant elements.

A4.3.2

A4.3.3 Workshop or circle of Frans Hals, Portrait of a 26-year old man, 1632

Oil on canvas, 62.5 x 52.0 cm, inscribed and dated upper right: ÆTATIS SVÆ 26 / AN° 1632

Bordeaux, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux, inv.no. Bx E 310

Several specialists agree that the inscription has been reworked; previously, the words FRANZ HAALS / PINXIT had been visible underneath the age of the sitter and the date of the painting. These were probably added by a later hand, and may cover a previous, different signature.1

The painterly style does not correspond to Hals’s typical manner of painting. The jaunty facial expression and the dynamic posture of the sitter may have been due to the model, but could equally be a pictorial invention by a, probably Flemish, painter. The position of the hands, of which the fine gradient in the modelling was recently revealed during restoration, is not a typical portrait gesture, but would rather match the visual rhetorics of history painting.

A4.3.3

© Mairie de Bordeaux, Musée des Beaux-Arts, photo: F.Deval

A4.3.4 Workshop or circle of Frans Hals, Portrait of a man with a hat, c. 1632

Oil on canvas, 64 x 52 cm

Gotha, Schlossmuseum Schloss Friedenstein, inv. no. SG 690

This is a picture which is more ‘Halsian’ than actually carried out by Hals. It combines the verve of Hals’s compositions – with a figure arranged in the composition diagonally, in arrested movement – with an expression of the sitter’s cheerful disposition. The face is very close to Hals’s own portraits; it is confidently captured in the modelling of light and shade. However, this observation is based only on the eyes, the corners of the nose and the mouth; the surrounding small swellings and creases are ignored. The smooth execution of the surface conveys a formal expression. In contrast to Hals’s autograph works, the upper body and arms appear slightly reduced in size. This leads to a lack of three-dimensional volume which would be uncharacteristic in a work by Hals. The composition overemphasizes the highlights on the sleeve, which is atypical as well.

A4.3.4

A4.3.5 Workshop of Frans Hals, Portrait of a man, c. 1633-1635

Oil on panel, 24.7 x 19.5 cm

United States, private collection

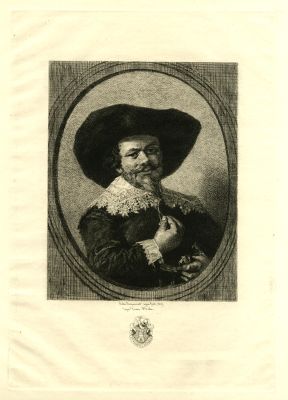

This small picture was once highly prized. In 1881, it achieved the enormous sum of 30.000 francs at auction in Paris.2 For reasons unknown, it was associated with the name of Willem van Heythuysen (c. 1585-1650) in the catalogues by Bode, Moes, Bode & Binder and Valentiner.3 However, there is no resemblance to this person when compared to his certain portraits (A2.6, A3.24). It is possible that this identification derived from the title that is included in a state of Jules Jacquemart's (1837-1880) 1867 etching, made after the painting [2].

The smooth and sluggish rendering of the figure and the hard brushstrokes in the facial area rule out that this painting was created by Hals himself. Nevertheless, the portrait is a typical work that is executed in his style, perhaps even on the basis of a sketch by him and created in his immediate surroundings. In addition, the angularity of the brushwork suggests a certain proximity to Harmen Hals (1611-1669).

A4.3.5

© Sotheby’s 2023

2

Jules Jacquemart

Portrait of a man identified as Willem van Heythuysen, dated 1867

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1871,0610.816

A4.3.6 Workshop of Frans Hals, Portrait of a man in a painted oval, c. 1635

Oil on canvas, 94 x 72.4 cm

Woburn Abbey, The Duke of Bedford

While the composition, subject matter, and modelling of the light in this painting are indisputably attributable to Frans Hals, the painterly execution is not. The surface modelling demonstrates an uncharacteristic smoothness. The light reflections and the highlighted edges on the cuffs, collar, and in the face are drawn in fine straight lines. The same applies to the beard, as well as to the area of the glove. The result is a more rigid facial expression than we see in Hals’s own fluidly applied and repeatedly blurring style of painting. In this instance, we may either assume the painting is a repetition that was executed in the workshop, or that there is a preparatory sketch by Hals underneath the finishing paint layer. The posture of the gentleman resembles that in the 1635 Portrait of a man (A1.72), yet the size of the visible composition in the painted oval frame detail differs from that of the other oval portraits. Therefore, an association with a female pendant, as suggested by several authors, is not convincing. The combination of the small copy and its pendant, published by Valentiner in 1921 and in the catalogue of the 1937 Hals exhibition (A4.3.6a), suggest that the present portrait can be associated with the Portrait of Marie Larp (A1.79) in the National Gallery, London [3].4 However, that painting is 10 cm shorter in height. Because of this significant difference in size, and the lack of stylistic parallels between the portraits, such a connection cannot be established.

A4.3.6

© Woburn Abbey and Gardens

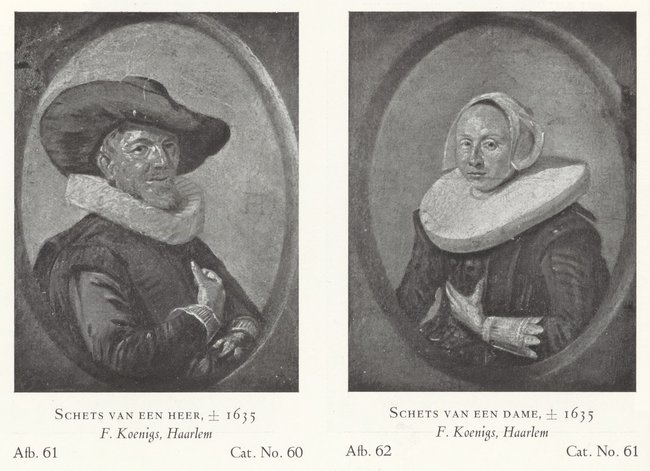

A4.3.6a Anonymous, Portrait of a man in a painted oval

Oil on paper, mounted on panel, 18.7 x 13.7 cm

Formerly Haarlem, private collection F. Koenigs

This small copy was published by Valentiner in 1921 and in the catalogue of the Hals exhibition in 1937.5 It was put forward as the pendant of a copy of the Portrait of Marie Larp (A1.79) [3].

3

Page from Haarlem 1937, cat.no. A4.36a depicted on the left

A4.3.7 Workshop of Frans Hals, The lute player, c. 1634-1640

Oil on canvas, 83 x 75 cm, monogrammed lower right: FH

Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland, inv.no. NGI.4532

This painting was reproduced in a mezzotint by John Faber (1694-1756) in 1754, with an inscription identifying it as a work by Frans Hals [4]. It is consistent with other works by Hals and his workshop in what concerns the rendition of the sitter, who turns toward the viewer. Moreover, the lighting and modelling of the hands, and most importantly, the diagonal structure of the composition suggest such an origin.

Art historians that have previously rejected the attribution to Hals based their argument on the assumption of authorship by a different, independent painter, rather than basing their judgement on the concept of a workshop production. This explains why Hofstede de Groot, Plietzsch and Slive suggested an attribution to Judith Leyster (1609-1660), who for a long time was the first choice for problematic ‘Hals’ works.6 Slive pointed to the close relationship between the modelling of the lute player’s right hand and the same hand in The violin player in Virginia (A4.2.8b). Yet, both these well-modelled hands match less convincing with the hands we see in Leyster’s work, than with those by Hals. Separate templates for specific motifs such as these could have only been available in the stock of the Hals workshop.

Hofrichter included the present painting in her monograph on Leyster as Portrait of a Lute Player, thus emphasizing that this is not a typical genre painting representing the performance of an anonymous actor in a stage costume, or that of a fool, but rather a portrait comparable to that the Portrait of Daniel van Aken (A4.3.9) and hence a commission. As such, Hofrichter suggested that the painting needs to be understood as a representation of an elegantly dressed gentleman playing the lute – a portrait in action – with an unusually emphasized attribute. I agree with Hofrichter’s interpretation, but I think that this special painting was created within the Hals workshop, aided by separate preparatory studies by Hals himself, if only for the face and hands alone. The manner of execution imitates Hals’s brushwork, albeit unrhythmically and without achieving Hals’s ease. Stylistically, it can be placed in the middle of the 1630s, when Leyster had long been working independently. We could ask why she would once again abandon her established personal style I visible in for instance the Boy playing the flute of c. 1635 – in order to take over a work that was meant to bear the signature of Hals?7

In 2017, Dudok van Heel proposed a new identification of the sitter as Floris Soop (1604-1657), on the basis of archival documentation. Floris Soop, the second son of Jan Hendricksz. Soop (1578-1638) (A1.83), was one of the Regents of the Amsterdam theatre and clearly musically gifted. In 1709, a painting described as a depiction of ‘the celebrated lute player Soop by Hals’ was offered for auction in Amsterdam – quite possibly the present Dublin lute player.8 The inventory of Floris Soop’s possessions that was drawn up after his death in 1657, lists about 140 paintings, yet without any artist’s name. There is also a listed item referred to as ‘musyckcamertje’ – or music room – containing a lute, three violas da gamba, and a portrait of Floris Soop.9 Evidently, the portrait of Floris Soop by Frans Hals that was mentioned in the 1709 sale, must have derived from the estate of the family. And unquestionably, the description matches the portrait of the lute-playing noble young gentleman in Dublin quite well.

In Floris Soop’s estate inventory of 1657, the following portraits were listed in the ‘Voorhuis’ – the reception room at the front of the Amsterdam Glashuys: ‘The portrait of the old captain Jan Soop, ditto of Jan Soop, ditto of Floris Soop, ditto of Pieter Soop, ditto Floris Soop lifesize’.10

In 1661, when the next succession took place in the Schrijver-Soop family, the pictures were then listed with the names of their painters: ‘a likeness of the old captain Soop done by Hals, a ditto of the younger Jan done by Hals, a ditto of Floris Soop, a ditto of Peiter Soop done by Hals, a small ditto of the younger Jan Soop’.11 In addition, there hung ‘a likeness of captain Soop with a dog’ and a ‘ditto of Floris Soop lifesize’.12 Dudok van Heel interpreted the ‘ditto’ not merely as a reference to the sitter: ‘The mention of the painting of Floris Soop in the inventory does not state that it was painted by Frans Hals, but this is entirely within the realm of possibility’.13

Overall, Van Eeghen had already noted that there must have been three portraits of Floris Soop: one in a row with the portraits of the father and brothers, another making music, and a third in life size. This third picture was connected by Van Eeghen to a painting which also appeared in the 1709 Amsterdam auction, where lot 34 describes ‘a flag bearer by Rembrandt’. This most probably referred to Rembrandt’s Portrait of Floris Soop of 1654 [5]. Even though the name of Rembrandt did not appear in the inventories of paintings owned by Floris Soop, nor of his heir Willem Schrijver (1608-1661), Van Eeghen noted that Floris Soop had been one of the few long-term flag bearers in one of Amsterdam’s civic guards, which would match the representation of a relatively old sitter by Rembrandt.14

Two identifications of Floris Soop then exist in parallel: that of the lute layer and that of the flag bearer. Even considering that Floris Soop must have been about 20 years younger in the painting by Hals, there are still differences in the two faces. The outline of the eyes, the ridge of the nose, the shape of the eyelid, the eye sockets and eyebrows differ. Last, not least the eye color is dark brown in Rembrandt and green-grey in Hals. In addition, the shape of the chin and position of the ears are incompatible: high in Hals, low in Rembrandt. Thus, we are faced with two competing lines of reasoning, which are mutually exclusive. Both contain arguments of some probability but are not fully compelling. Both paintings appeared in the 1709 Amsterdam auction, 52 years after the death of the presumed sitter. Both match particular abilities and characteristics of the sitter, which, however, could also match one or another contemporary individual. Finally, the connection between the Dublin painting and a portrait of the famous lute player Floris Soop by Hals is more consistently documented. In addition, Norbert Middelkoop recently suggested an alternative identification for Rembrandt’s Flag bearer.15

A4.3.7

Photo © National Gallery of Ireland

4

John Faber (II)

The Lute Player, dated 1754

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-17.758

cat.no. C37

5

attributed to Rembrandt

Portrait of Floris Soop, dated 1654

New York City, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 49.7.35

A4.3.7a Anonymous, The lute player

Oil on canvas, 82.5 x 74.9 cm

Sale London (Sotheby’s), 25 June 1947, lot 65

This is a rather faithful copy after The lute player in Dublin (A4.3.7). Possibly, John Faber (1694-1756) based his mezzotint of 1754 [4] on this copy instead of on the Dublin original.16

A4.3.7a

© National Gallery, London

A4.3.8 Workshop of Frans Hals, possibly Frans Hals (II), Portrait of a woman holding a fan, c. 1640-1642

Oil on canvas, 79.8 x 59 cm

London, National Gallery, inv. no. NG2529

This portrait of an elaborately dressed woman can be dated to the beginning of the 1640s, based on the style of her dress, and especially of her lace-trimmed cap with the downward points.

The canvas was cut along the sides and the lower edge, which is demonstrated by the hand in the lower left corner, which is abruptly cut off. The lighting and the face that are turned in the opposite direction of the body, with the gaze turning even further towards the viewer, are in keeping with Hals’s approach. Yet, the somewhat constrained-looking body position and the stiff arm and hand movements lack the typical vibrancy of his figures. The light parts of the face and hands are characterized by a focus on contours created by abrupt shadows, resulting in a two-dimensional appearance. The hard contours of the eyes and the uniformly drawn line of the mouth immobilizes the facial expression. These features are typical for a strictly illustrative, less visual, and not spontaneous approach to the observation of facial features and gestures.

A4.3.8

A4.3.9 Workshop of Frans Hals, possibly Frans Hals (II), Portrait of Daniel van Aken playing the violin, c. 1640-1645

Oil on canvas, 67 x 57 cm

Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, inv. no. NM 1567

This painting is inadequately preserved, and the format was probably reduced on all four sides. The original composition is documented in a drawing by Matthias van den Bergh (1615-1687), which also provides the sitter’s name [6]. The suggested curtain behind the sitter on the left in the drawing is worth noting, as it creates a similar stage-like setting as in the engraving after the Portrait of Isaac Abrahamsz. Massa (C27, A4.1.11). Similar to the Lute player in Dublin(A4.3.7), it may be assumed that Hals created the present painting on commission, depicting the sitter with attributes referring to his profession. It is worth asking to what extent such a portrayal of a gentleman making can be read allegorically. Was the representation of the sitter, rendered in the act of playing an instrument, qualified as a demonstration of the transience of sensual experiences relating to the concept of vanitas, comparable to the motif of a skull? If this was indeed perceived as a self-evident concept, this also says something about the reception of other portraits. Unfortunately, nothing is known about Daniel van Aken, or why he wanted his likeness immortalized in this way.

The portrait’s two-dimensional appearance is due to the fact that it has been more drawn than painterly modelled with graduated tones. The areas of the collar, face, and hands are characterized by an emphasis on the contours, and a flat style rendering, lacking Hals’s important halftones. This manner of execution can be attributed to the hand of an assistant, possibly the same painter whose hand appears in many later portraits, and who might be identical to Frans Hals (II).

A4.3.9

Photo: Anna Danielsson / Nationalmuseum

6

Matthias van den Bergh

Portrait of Daniel van Aken, dated 1655

Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, inv./cat.nr. MJvdB 1 (PK)

cat.no. D58

A4.3.10 Workshop of Frans Hals, possibly Frans Hals (II), Portrait of an unknown man, 1643

Oil on panel, 31.8 x 27.9 cm, monogrammed and dated lower right: FH / 1643

Sale Vienna (Wiener Kunst Auktionen), 2003-10-28, lot 7

This painting was offered for sale at Sotheby’s New York in 1999, catalogued as merely ‘in the manner of Frans Hals’, and created in the mid-19th century.17 The subsequent years, it underwent chemical analysis in Munich and London, in order to establish its age. The examination confirmed that the pigments used in this painting correspond to those that were in use during the 17th century.

The thin-lined execution of the face, with the beard hairs going in all directions, and the too small hand which appears like an appendage, differentiate this portrait from the convincing three-dimensional quality and the life-like compositions of Hals’s autograph portraits, which in addition display a facial movement which corresponds to the body posture.

A4.3.10

© Wiener Kunst Auktionen

Notes

1 See Le Bihan 1990, no. 34.

2 Sale Paris, 30 May – 6 June 1881, lot 11 (Lugt 41161).

3 Bode 1883, p. 43; Moes 1909, no. 47 ; Bode/Binder 1914, no. 226; Valentiner 1923, p. 165.

4 Valentiner 1921, p. 139; Haarlem 1937, no. 60, 61.

5 Valentiner 1921, p. 139; Haarlem 1937, no. 60, 61.

6 Hofstede de Groot 1893, p. 198; Plietzsch 1956, p. 187; Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, no. D 25.

7 Judith Leyster, Boy playing the flute, oil on canvas, 73 x 62 cm, Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, inv.no. 1120.

8 Sale Amsterdam, 19 April 1709, lot 30 (Lugt 220).

9 Van Eeghen 1971, p. 180; Dudok van Heel 2017, p. 33-34.

10 ‘t conterfeytsel van den ouden capitein Jan Soop, Idem van Jan Soop, Idem van Floris Soop, Idem van Pieter Soop, Idem Floris Soop soo groot as het leven’. Dudok van Heel 2017, p. 31.

11 ‘Een conterfeytsel van de oude capitein Soop door Hals gedaen / Een dito van de jonge Jan Soop door Hals gedaen / Een dito van Floris Soop / Een dito van Pieter Soop door Hals gedaen / Een kleyn dito van de jonge Jan Soop’. Dudok van Heel 2017, p. 31.

12 ‘een conterfeytsel van capitein Soop met een hondt’ / ‘Idem noch van Floris Soop soo groot als het leven’. Van Eeghen 1971, p. 180-181.

13 Dudok van Heel 2017, p. 31.

14 Van Eeghen 1971, p. 181.

15 Middelkoop 2020, p. 92-98.

16 Hofrichter 1989, p. 63.

17 Sale New York (Sotheby’s), 14 October 1999, lot 104.