A4.3.41 - A4.3.50

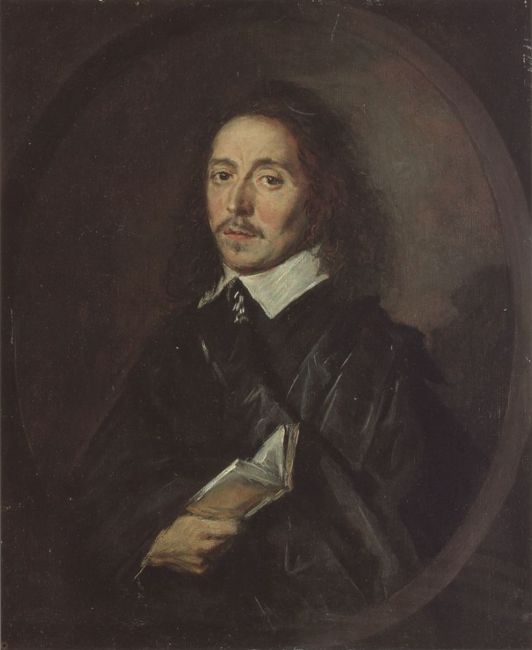

A4.3.41 Workshop of Frans Hals, possibly Frans Hals (II), Portrait of a seated man, c. 1650-1652

Oil on canvas, 91.2 x 71.6 cm

Amiens, Musée de Picardie, inv. no. M.P.Lav. 1894-94

This painting imitates the pose of the sitter in the Portrait of a seated man of c. 1645 (A4.3.16), with the arm over the back of the chair, yet it is executed in a softer and more colorful style. Cleaning of the surface revealed a lively tonality in the shades of the face. My earlier identification of the painter as Jan Hals (c. 1620 - c. 1654) was incorrect.1 If an attribution is at all possible, it would be to the group of works by an imitator, who might be identical with Frans Hals (II) (1618-1669).

A4.3.41

© Collection du Musée de Picardie, Amiens photographies Marc Jeanneteau/Musée de Picardie

A4.3.42 Workshop of Frans Hals, possibly Frans Hals (II), Portrait of an unknown man, c. 1652-1655

Oil on canvas, 108 x 80 cm

Vienna, Liechtenstein - The Princely Collections, inv. no. GE 235

In the literature, the present painting was associated with the Portrait of a woman (A4.3.23) as a companion piece.2 This assessment was probably influenced by the fact that both pictures had hung together since 1873. The catalogue entry for the above-mentioned female portrait explains the reasons for a separate attribution. In addition, the execution of the male portrait also differs stylistically. The brushwork is more stripy, with a pronounced dissolution into separate layers of brushstrokes – especially in the areas of the face and hands, as well as in the demarcation between the silhouette and the background. The composition and the almost frontal angle of the face are close to the Portrait of a man in Washington (A3.57).

Yet, while the present painting is dominated by hard contours, the Washington portrait displays a repeated creamy blurring of the paint layers in a soft application of the shades in the face and hands – resulting in a sequence of attractive visual transitions. In the present painting, the lines around the eyes, the edge of the cheek, the mouth, and the fingers are drawn much too harshly and indicate a clutching to the depiction of ‘objective’ elements – in contrast to Hals’s consistently ‘optical’ representation. The human psychology of visual observation tends to record objects in their characteristic expansion and limitation. Conversely, Hals's reduction of his perceptions into subjective visual impressions of islands of light, shade, and color creates an unusual act of abstraction. Such a radical transformation of visual observations was incomprehensible for Hals's assistants. They only imitated their master’s spontaneous technique, which is evidenced in the present painting by the unnecessary cross-hatching in the sections of the hand and glove. While the master never lost the connection with the anatomical structure, the assistant did not have this ability, as the cut-off shoulder and the general flatness of the figure here demonstrate. It is possible that Hals designed the composition and the facial contours, but the painted surface which is visible today does not show his brushwork [1]. The contrast with Hals's own modelling can also be seen in comparison with his Portrait of a man in Rochester (A3.55), which displays a facial area with subtle transitions of brightness [2].

A4.3.42

© LIECHTENSTEIN. The Princely Collections, Vaduz–Vienna

1

Detail of cat.no. A4.3.42

2

Detail of cat.no. A3.55

Frans Hals (I) and workshop

Portrait of a man, c. 1650-1652

Rochester, Memorial Art Gallery

A4.3.43 Workshop of Frans Hals, Portrait of an unknown man, c. 1655

Oil on panel, 36.5 x 29.9 cm

Sale London (Christie’s), 18 December 1998, lot 266

The face in this portrait is related to other workshop executions from Hals's late phase, and close to the manner we associate with Frans Hals (II) (1618-1669). While the contours of the hand with the book, and the diagonal folds of the clothing superficially refer back to Hals's creative model, they are unconnected to the shape and position of the body. The anatomical comprehension, the psychology of movement, and the facial expression that are typical for Hals's portraits are largely absent in this instance.

A4.3.43

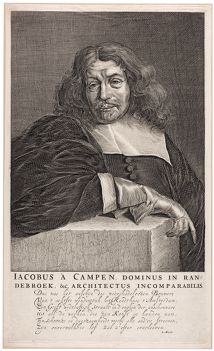

A4.3.44 Workshop or follower of Frans Hals, Portrait of Jacob van Campen

Oil on panel, 58 x 45 cm

Amiens, Musée de Picardie

Jacob van Campen (1596-1657) was a highly respected painter and architect of famous buildings, above all the Amsterdam town hall and the Mauritshuis in The Hague. He was also involved in the construction of the castle Huis ten Bosch near The Hague. He came from a distinguished Haarlem family and his relationship with Frans Hals probably grew out of his local connections with family and friends.

Hofstede de Groot identified the sitter on the basis of the resemblance with a reverse engraving by Abraham Lutma (1628-1692), which served as the frontispiece for a book on the Amsterdam town hall [3].3 It is remarkable that such a cultivated and socially well-connected connoisseur should have chosen a portraitist like Hals, with a comparatively provincial background and an unconventional style. Furthermore, the commission happened at a time when Hals himself produced very little, apparently having delegated part of the execution of his commissions to assistants in his workshop. Van Campen himself had painted excellent portraits, and historical and mythological subjects in a smooth, classicist style. Strangely enough, Hals’s stiff portrait is the only pictorial commemoration that captures this important personality.

When looking at the angular style and the gloomy expression of the sitter, this portrait is most closely related to the Portrait of an unknown man in the Liechtenstein collection (A4.3.42) and the Portrait of Theodor Wickenburg (A4.1.17). Today, the difference with Hals’s autograph manner has become more apparent to me than ever before, even though I cannot identify the assistant whose hand was involved in Hals’s later period. The difficulty of identifying unsigned and undocumented participation is an intrinsic element in the research of historical workshop production.

In this instance, Hals was probably tasked with creating a portrait study which would serve as the model for the illustration of the architectural publication. If we take the tense and suffering facial expression seriously, the sitter might have already been ill at the time the portrait was made, and he may have been looking for a solution to present his likeness as an introduction to his printed oeuvre. Naturally, the elderly Hals could deliver a painted portrait sketch – on paper? – for this purpose. In turn, an ambitious engraver could develop the portrait further into a half-length figure. What may have been a labored posture of a model during a portrait session, possibly the reason for the peculiarly skewed position in the painting, was reinterpreted as an elegant pose in the print, leaning against a stone balustrade. The hand with the glove was added and the dark hat removed.

Interestingly, there is a drawing in the Amsterdam Print Room which shows the sitter in the same position as in the engraving, but with the hat from the painting [4]. It is signed with the monogram IL for Jan Lievens (1607-1674), which is not credible, but does not necessarily discredit the representation as such. Hofstede de Groot suspected that it is an 18th-century forgery, while Slive assumed it to be a pasticcio by an unknown copyist.4 In any case, this composition illustrates the different elements which were combined in Lutma’s engraving.

Once the painted modello for the engraving was ready, it could also be developed into a portrait painting – work that Hals could delegate to an assistant. Possibly, the result was the present painting, even though it was cut slightly on all sides in the meantime; the drawing by Warnaar Horstink (1756-1815) dated 1798 records the original format [5]. The inscription on the back of this drawing notes that it was made ‘after the painting by Frans Hals which is located in the country estate of Randenbroek near Amersfoort that Van Campen had created’.

A4.3.44

© Collection du Musée de Picardie, Amiens; photographies Marc Jeanneteau/Musée de Picardie

3

Abraham Lutma

Portrait of Jacob van Campen (1596-1657), c. 1655-1661

The Hague, RKD – Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis (Collectie Iconografisch Bureau)

cat.no. C51

4

Anonymous c. 1661-1700

Portrait of Jacob van Campen, c. 1661-1700

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-T-1885-A-481

cat.no. D76

5

Warnaar Horstink

Portrait of Jacob van Campen, dated 1798

Haarlem, Noord-Hollands Archief, inv./cat.nr. NL-HlmNHA_53013654_K

cat.no. D75

A4.3.45 Workshop of Frans Hals, possibly Frans Hals (II), Portrait of a young woman, c. 1655-1658

Oil on canvas, 60 x 55.6 cm

Hull, Ferens Art Gallery, inv. no. 526 KINCM:2005.5003

This painting was first published in 1952.5 Stylistically, it is related to several female portraits from c. 1645-1650 (A4.3.20, A4.3.21, A4.3.23, A4.3.30, A4.3.33, A4.3.35). An overemphasis of the object-defining contours – in the sense of ‘consciously aware’ – is a common feature in all of these, for example along the shadow of the nose, the line of the mouth, and the contour of the right cheek [6]. This contrasts with the visually captured dark zones in the facial areas that are executed by Hals himself. Such a visual recognition can be observed in the difference between the shadows cast under the nose of Dorothea Berck (A1.112) [7] and under the nose and chin of Isabella Coymans (A1.120) [8], compared to the lighter modelling shades in the same areas. Accordingly, the present picture captures not so much the gentle roundness of the facial muscles, than the demarcating lines along the nose and mouth as well as the crease in the cheek. These edges are unmistakably strengthened, especially the line of the mouth. This leads to a frozen smile as the only indication of facial expression. The bonnet, collar and bow are represented in a drawn manner which is associated with the execution of a number of areas in the Regentesses of the Old Men's' Almshouse (A3.63).

A4.3.45

© Ferens Art Gallery / Bridgeman Images

6

Detail of cat.no. A4.3.45

7

Detail of cat.no. A1.112

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Dorothea Berck, 1644

Baltimore Museum of Art

photograph by Mitro Hood

8

Detail of cat.no. A1.120

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Isabella Coymans, c. 1646-1648

private collection

A4.3.46 Workshop of Frans Hals, possibly Frans Hals (II), Portrait of a man, c. 1655-1658

Oil on canvas, 104 x 84.5 cm, monogrammed lower right: FH

Copenhagen, SMK – National Gallery of Denmark, inv. no. KMS3847

In 1929, this picture came to Copenhagen from the substantial Hals collection of the Berlin museums, as an exchange with a Rubens landscape. The face, accentuated in broad brushstrokes, and the broad, large hands demonstrate the ponderous quality of the painting. The portrait indicates the involvement of the late Hals workshop, which was dominated by the assistant who created the figures in the two family portraits in London (A4.3.19) and Madrid (A4.3.24).

A4.3.46

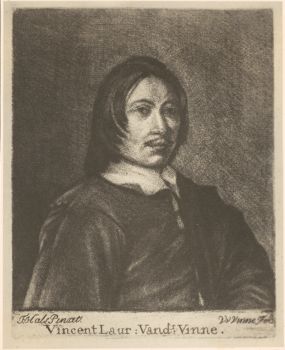

A4.3.47 Workshop of Frans Hals, possibly Frans Hals (II), Portrait of Vincent Laurensz. van der Vinne, c. 1658-1660

Oil on canvas, 64.7 x 48.9 cm

Toronto, The Art Gallery of Ontario, inv. no. 54/32

Vincent Laurensz. van der Vinne (1628-1702), who was Frans Hals’s pupil for nine months in 1646-1647, was a versatile and accomplished figure from Hals’s circle. On 21 August 1652 he set out on a journey to Germany, Switzerland and France, from which his illustrated travel diary survives.6 After his return to Haarlem, he was active as a poet and a painter of landscapes, still lifes, history- and genre paintings, and portraits. According to Arnold Houbraken (1660-1719), he accepted all manner of commissions, even those for shop signs, so that the painter Job Berckheyde (1630-1693) is said to have given him the derisive nickname ‘Raphael of Sign Boards’.7 However, Houbraken emphasized Van de Vinne’s abilities as a portrait painter, with forceful brushwork in the style of his master Frans Hals. He is, therefore, as Slive noted, a possible candidate for the authorship of various paintings from the 1640s and 1650s that are painted in the manner of Hals.8

Unfortunately though, the extant portraits that can be attributed to Van der Vinne, do not provide any guidance in this matter. A secure attribution to him would be the 1651 Self-portrait in the Frans Hals Museum, which only slightly resembles the present portrait [9].9 A large-scale vanitas still-life in the same museum, which includes a drawn portrait of the artist – copied after a drawing by Leendert van der Cooghen (1632-1681) – is also a secure work by his hand.10 The portrait drawing by Van der Cooghen depicts the sitter with a more slender face and a long narrow nose [10]. A comparison with the present picture makes the difference in quality apparent. Here, the expression in the eyes is lackluster, without the direct, active gaze which dominates the energetic faces of Hals’s sitters. Overall, the facial features are indistinct, even though a focus on the eyes and precise characterization of the features are central elements of portraiture. In this respect, the drawing by Van der Cooghen is more expressive. The only characteristic the present portrait has in common with the other likenesses of Van der Vinne, are the heavy upper eyelids. Lastly, though not unimportantly, the identification of the present portrait is based on a mezzotint that reproduces it in a cursory way [11]. It is marked Vincent Laur: Vandr.Vinne and inscribed on the lower left F.Hals Pinxit. After it had long been regarded as a work by the sitter’s own hand, it is attributed more convincingly today to his grandson Vincent Laurensz. van der Vinne (II) (1686-1742).

To be fair, the current condition of the Portrait of Vincent Laurensz. van der Vinne should not be taken at face value, since some of the modelling shadows and facial lines – such as the creases around the eyelids – were probably lost through cleaning. Several copies of the pictures show a concurrent original appearance, such as the drawing by Louis de Moni (1698-1771) (D81), and several watercolor copies (D80, D82, D83). Overall, the face in the present picture appears with unmoved features in a predominantly linear design. The patchy application of paint is detached from the three-dimensional modelling typical of Hals's autograph works. While Hals himself cannot be considered for an attribution in this case, an assistant certainly can, whom I assume to have been Frans Hals (II) (1618-1669). This would certainly match the inscription on the mezzotint, which refers to either the older or the younger Frans Hals.

A4.3.47

Photo: © AGO

9

Vincent Laurensz. van der Vinne (I)

Self-portrait of Vincent Laurensz. van der Vinne (1628-1702), dated 1651

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv./cat.nr. OS I-243

10

Leendert van der Cooghen

Portrait of Vincent Laurensz. van der Vinne (1628-1702), early 1660s

Berlin (city, Germany), Kupferstichkabinett der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, inv./cat.nr. 4378

cat.no. D93

11

Vincent Laurensz. van der Vinne (II)

Portrait of Vincent Laurensz. van der Vinne I (1628-1702)

Haarlem, Noord-Hollands Archief, inv./cat.nr. NL-HlmNHA_53014201_K

cat.no. C53

A4.3.47a Anonymous, Portrait of Vincent Laurensz van der Vinne

Oil on panel, 63.0 x 47.5 cm

Dresden, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Gemäldegalerie, inv.no. 1362

Copy after the portrait in Toronto.

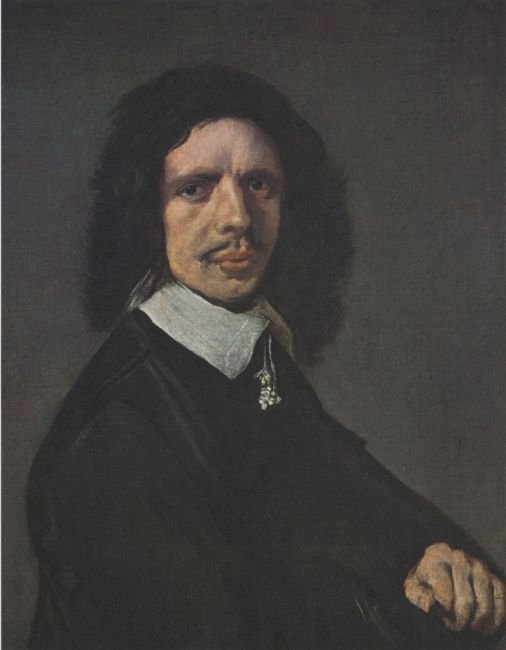

A4.3.48 Workshop of Frans Hals, possibly Frans Hals (II), Portrait of an unknown man, c. 1658-1660

Oil on canvas, 63.5 x 48.9 cm, monogrammed lower right: FH

Sale New York (Christie's), 11 January 1991, lot 83

Pendant to A4.3.49

A4.3.48

A4.3.49

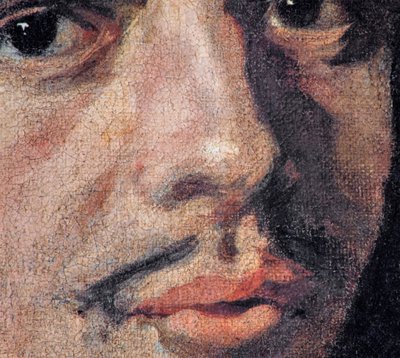

The surface of this painting is strongly abraded. The overall execution is coarse and lacks the plasticity and virtuoso ease of modelling we encounter in autograph works by the master. Nevertheless, the face and the hand are drawn accurately – with pointed shadows of the mouth and under the lower eyelids that may have been executed by Frans Hals himself [12]. The intense and emphasized gaze with the suggested creases in the forehead is quite dominant and could well be based on a design by Hals himself. The underlying melancholic disposition of the sitter – often a result of the tedious sitting-sessions for a portrait – connects this painting to other works from the group of paintings that is tentatively attributed to Frans Hals (II) (1618-1669). According to clothing, hairstyle, and manner of execution, it can be dated to ca. 1658-1660.

12

Detail of cat. no. A4.3.48

Photograph taken by C. Grimm in the 1970s

Thin underdrawing is visible beneath the lower lip

A4.3.49 Workshop of Frans Hals, possibly Frans Hals (II), Portrait of an unknown woman, c. 1658-1660

Oil on canvas, 64 x 49 cm, monogrammed lower left: FH

Sale New York (Christie's), 11 January 1991, lot 83

This painting suffers from the same condition issues as its abovementioned pendant: the surface of the bonnet, the collar and the cuff is much abraded. The detailing has mostly disappeared in these areas. The modelling of the hand and face has also become very thin. The picture stands out among the late female portraits because of the emphasis on the area of the eyes, and the melancholic expression. An initial design by Frans Hals may have formed the basis for this portrait.

A4.3.50 Workshop of Frans Hals, possibly Frans Hals (II), Portrait of an unknown woman, c.1658-1660

Oil on panel, 44.5 x 34.3 cm, monogrammed lower right: FH

Oxford, Christ Church Picture Gallery, inv. no. P0589

The best executed section in this painting is the face; possibly its initial design was by Hals himself. However, light reflections and shadows have been applied in a harsh manner, similar to the handling in other paintings which we attribute to Frans Hals (II) (1618-1669).

The small panel is beveled along three edges; the fourth edge was already very thin due to the wedge-shaped cut of the board. The tapering edges were created to protect the panel against the effects of humidity. While its front is covered with paint and the reverse impregnated with oil or another agent, moisture can enter from the edges, which were therefore reduced, possibly also to fit more easily into a frame. Groen and Hendriks found traces of an underdrawing to the right of the head.11 This may indicate that other paintings from the Hals workshop may also turn out to bear underdrawings, when inspected with infrared reflectography. Such examinations may reveal clues about the nature of cooperation between Hals and his assistants.

A4.3.50

© Christ Church, University of Oxford

Notes

1 Grimm 1971, p. 155.

2 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 96.

3 Hofstede de Groot 1915, p. 16-18. Afbeelding van ’t Stadt Huys van Amsterdam, in dartigh coopere plaaten […], Amsterdam 1661.

4 Hofstede de Groot 1915, p. 18; Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 126.

5 Martin 1952.

6 See Sliggers 1979.

7 Houbraken 1718-1721, vol. 2, p. 210-211.

8 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 1, p. 187.

9 Vincent Laurensz. van der Vinne (I), Self-portrait, 1651, oil on panel, 25 x 20 cm, Haarlem, Frans Hals museum, inv. no. OSI-243.

10 Vincent Laurensz. van der Vinne (I), Still life with a portrait of the artist by Leendert van der Cooghen (1632-1681), c. 1643-1672, oil on canvas, 107.8 x 91.9 cm, Haarlem, Frans Hals museum, inv. no. OSI-342.

11 Washington/London/Haarlem, p. 127, plate VIII j.