C21 - C30

C21 Wallerant Vaillant, Two laughing boys

Mezzotint, 240 x 184 mm, signed lower left: W. Vaillant Fecit et Exc.

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. RP-P-OB-17.451

This mezzotint was most probably based on the monogrammed painting that was formerly in the Gould collection [1], and which can be considered to be an independent original by an assistant of Hals, instead of a copy.

C21

1

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Two laughing boys

canvas on panel, oil paint, 62 x 51 cm

center left: FH

formerly Washington, private collection Kingdon Gould

cat.no. A4.2.14

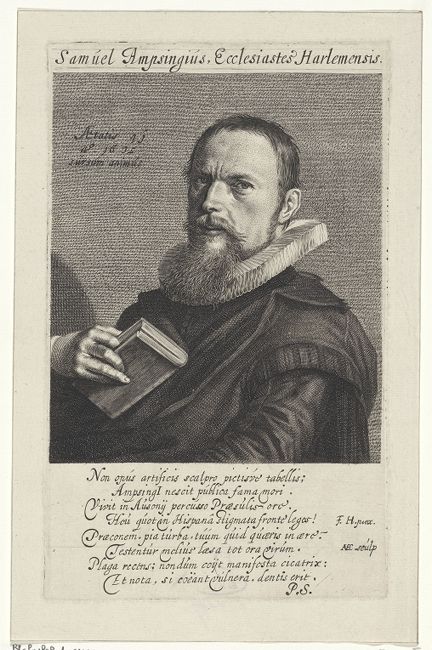

C22 Jan van de Velde, Portrait of Samuel Ampzing, 1632

Copper engraving, 200 x 123 mm, signed lower right: IANVLDE. Sculp. Dated upper left: ao 1632.

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. RP-P-1898-A-20197

The date on this engraving is 1632, the year when the sitter died at age 41. The eulogy verses under the portrait refer to his life achievements, as do those in the later, undated engraving by Jonas Suyderhoef (1614-1686) (C23). The text, which is signed P.S. (almost certainly referring to Petrus Scriverius (1576-1660)) reads as follows:

‘No need is there for sculptor’s chisel or painted canvasses;

Ampzing’s fame, known to all, cannot die.

It lives on in the stricken face of the Ausonian bishop.

Ah! How many scars will you read on the Spaniard’s brow!

Why, devoted congregation, do you seek to have your Herald pictured on copper?

The wounded faces of so many men will bear witness to him.

The blow is fresh; the open scar has not yet healed;

And, if the wounds do close, the toothmark will remain’.1

After a lost modello by Frans Hals, on which also the portrait of Samuel Ampzing (1590-1632), painted on copper, was based [2]. Overall, the representation is quite typical of Frans Hals, especially the suggested movement in the area of the eyes and eyebrows. Accordingly, there should have existed an accurate modello which was more lively than the somewhat hesitantly dashed execution of the painted portrait suggests.

C22

2

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Samuel Ampzing

copper, oil paint, 16.4 x 12.4 cm

New York, The Leiden Collection, inv.no. FH-100

cat.no. A4.1.9

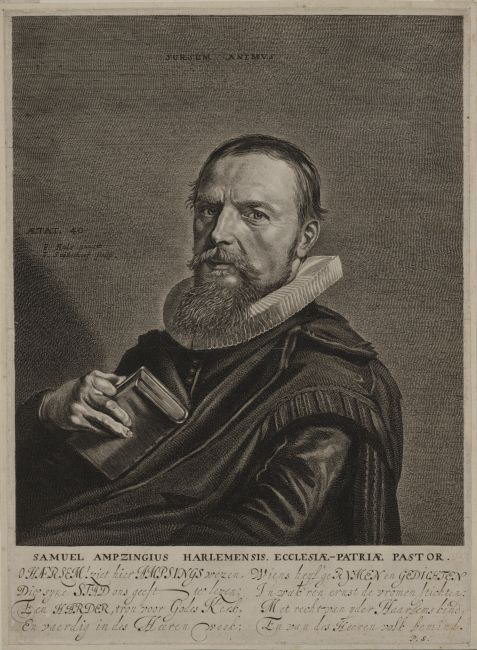

C23 Jonas Suyderhoef, Portrait of Samuel Ampzing

Copper engraving, 325 x 237 mm, signed centre left: I. Suijderhoef sculp.

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History

Similar to the print by Jan van de Velde (1593-1641) (C22), Samuel Ampzing (1590-1632) is presented with a poem below his portrait, signed with the initials P.S. that almost certainly can be interpreted as the signature of Petrus Scriverius (1576-1660). The eulogy reads as follows:

‘O Haarlem, look upon Ampzing’s appearance,

Which his city gives us that we may know him:

A shepherd true to the church of God,

And proficient in the Lord’s work,

Whose edifying verses and poetry uplift the pious with their deep gravity;

Rightly is he beloved of all Haarlem’s children and of the Lord’s people’.2

The different comments in the accompanying poems of both prints are remarkable, as they emphasize the sitter as the shepherd of the Church of God on the one hand, and as a fighter against the pope and the Spaniards on the other. Van Thiel pointed out that this can be explained by taking a look at who commissioned the prints. The Reformed Congregation had ordered the print with Ampzing’s likeness from Jan van de Velde, whereas the city of Haarlem commissioned a version from Jonas Suyderhoef (1614-1686).3

Liedtke concluded from the conciliatory wording on the present engraving that Suyderhoef’s representation must have been a much later version of the portrait, probably only made around 1640.4 He assumed this date on the basis of Suyderhoef’s earliest documented engraving, which is dated 1638.5 However, while Suyderhoef’s engraving matches the present painting on copper in terms of subject, its height and width are almost double and the perspective is wider. Thus, it must be based on a detailed modello with the same appearance, which would also have been the example for the earlier engraving by Van de Velde (C22).

Close reading of the details in both engravings and the painted version suggests that the modello has not been preserved. The form of the ear, the creases around the eyes and the design of the hand, but also the folds of the coat cannot be derived in every aspect from the respective parts of the preserved painting [2].

C23

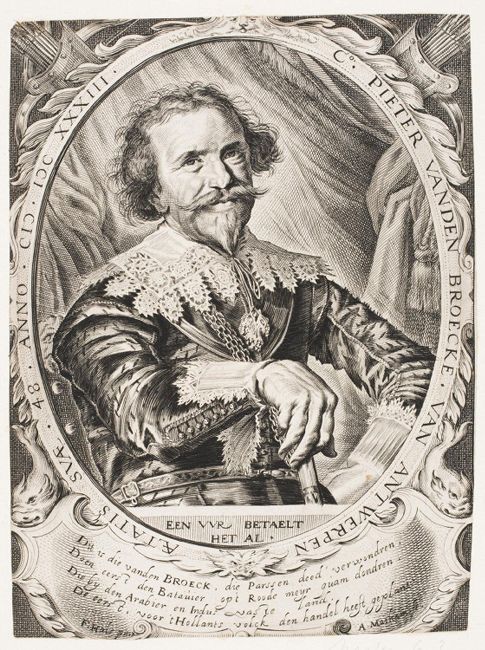

C24 Adriaen Matham, Portrait of Pieter van den Broecke, 1633

Copper engraving, 161 x 120 mm, signed lower right: A. Matham fe. Dated upper left: ANNO · CIƆ · IƆC XXXIII.

Philadelphia, Philadelphia Museum of Art, inv.no. 1985-52-34432

After the Portrait of Pieter van den Broecke (1585-1640) at Kenwood House (A1.58) [3]. The sitter’s motto is written down on the balustrade: ‘Een vvr betaelt het al’ (an hour repays it all). On the cartouche underneath the oval frame that surrounds the portrait, the text reads as follows:

‘Here the van den Broecke, the astounder of the Persians,

When the Batavian first came roaring across the Red Sea,

Who, on the continents of Arabia and Indus,

First fostered trade for the Dutch nation’.6

C24

3

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Pieter van den Broecke (1585-1640), 1633

Hampstead (Greater London), Kenwood The Iveagh Bequest, inv./cat.nr. 51 (88028830)

© Historic England Archive. Reuse not permitted

cat.no. A1.58

C25 Isaack Ledeboer, Portrait of Pieter van den Broecke

Copper engraving, 285 x 182 mm, signed lower right: J. Ledeboer del. et fecit.

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. RP-P-OB-46.467

This is a representation of Pieter van den Broecke (1585-1640) in a slightly elongated format when compared to the painted portrait (A1.58) and the 1633 print by Adriaen Matham (c. 1599-1660) (C24). Scientific analysis of the painting showed that the painting was cut along the lower edge. However, as Slive noted on the basis of the 1633 engraving, the loss was probably fairly small.7

It seems probable that Matham’s engraving was the model for Isaack Ledeboer (1692-1749), and not the painting. The strongest indication for this is the drapery in the background which does not appear in the painting, but is present highly similarly in the print. In Ledeboer’s engraving, the back of the chair is missing, giving the impression that Van den Broecke is standing. This elongated composition results in his right arm looking unnaturally twisted and emphasised, which was not intended in the painting.

C25

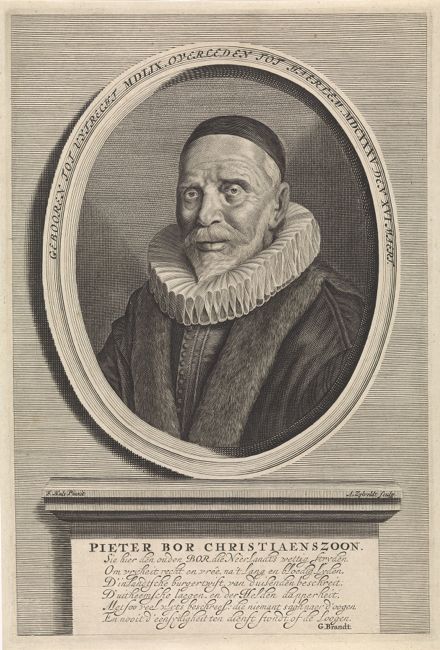

C26 Adriaen Matham, Pieter Christiaansz Bor, after 1637

Copper engraving, 315 x 195 mm, signed lower right: A. Matham. schulpsit.

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History

The comment inserted underneath the picture reads as follows:

‘Here you see Pieter Bor true to life.

After he worked with his pen:

and now listens to what you wish to praise or scrutinise.

When you write truth, it cannot suit everyone’.8

Pieter Christiaansz Bor (1559-1635) was the son of an apothecary from Utrecht. He settled in Haarlem in 1578 and worked there as a notary. By 1591 he continued his work in Leiden, and then in Rijswijk and Beverwijk before returning to Haarlem around 1602, where he died in 1635. In the final years of his life Bor received an annuity from the States General for his historical work, which he had undertaken for a long time in parallel to his profession as a notary. His work had already been published over many years. Bor’s grand historical work was his comprehensive account of the secession of the Netherlands: Oorsprongk, Begin, en Vervolgh der Nederlantsche Oorlogen (Origin, Beginning, and Continuation of the Dutch Wars), which was printed from 1595 to 1601 in 37 individual volumes. His portrait was intended for a complete print edition of his book, which Adriaen Matham (1599-1660) engraved after Bor’s death in 1637.

This superb engraving gives an impression of the original painting, which may have been identical to the portrait that was lost in the fire at the Museum Boijmans – housed at the Rotterdam Schielandshuis – on 10 February 1864.9 However, it is equally possible that Hals created a model of the sitter’s features on paper which was then used as the basis for the engraving and other painted copies. Matham’s engraving demonstrates both his own accomplished lucidity of representation and Hals’s skill for vivid portraiture. There are two earlier engravings after portraits of Bor which allow for comparison, as well as an engraving in reverse that was created a generation later by Anthony van Zijlvelt (c. 1640-in/after 1695), which again reproduces the image from Matham’s engraving in a reduced size (C26a).10 The latter was probably created in connection with the publication in Amsterdam in 1679 of a new edition of Bor’s magnum opus, comprising nine volumes. It is not clear why the image was reversed once more, after it had so convincingly captured the painted model with its natural light from the left.

C26

C26a Anthony van Zijlvelt, Portrait of Pieter Christiaansz Bor

Copper engraving and etching, 264 x 178 mm, signed lower right: A. Zylveldt Sculp.

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. RP-P-OB-24.763

C26a

C27 Adriaen Matham, Portrait of Isaac Abrahamsz. Massa

Copper engraving, 442 x 275 mm, signed lower centre: A. Matham. Sculpsit. C:M:

Haarlem, Noord-Hollands Archief, inv.no. NL-HlmNHA_53009764_M

After a lost modello by Frans Hals, dated 1635, on which also the painted portrait in San Diego [4] must have been based. Over the portrait, Isaac Massa’s (1586-1643) somewhat whimsical motto ‘In Coelis Massa’ (Massa in Heaven) is inscribed. The verses under the picture read as follows:

‘Pursued by hatred and envy, he obtained honour from the Tsar and the Swedish king.

And sought their favour, while fulfilling the commissions entrusted to him by the States.

When envy brought accusations upon him, he continued on his way, relying on God,

And obtained greater honours from the commander of the Goths, while laughing at envy.

Promoted now to the nobility, and having become rich, he now calmly awaits his eternal bliss’.11

Interestingly, the present copy of this print – which Slive noted as an especially good impression – bears Massa’s motto and signature in his own handwriting.12

C27

4

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Isaac Abrahamsz. Massa

panel, oil paint, 21.3 x 19.7 cm

center right: FH

San Diego Museum of Art, inv.no. 1946.74

© The San Diego Museum of Art: gift of Anne R. and Amy Putnam. www.SDMART.org

cat.no. A4.1.11

C28 Pieter de Mare, Portrait of an officer, possibly Jan Hendricksz. Soop

Etching and copper engraving, 332 x 276 mm

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. RP-P-OB-22.879

After the Portrait of a man in São Paulo [5]. The engraving shows the state of the painting prior to its later damages and retouches.

C28

5

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a man, possibly Jan Hendricksz. Soop (1578-1638), dated 1637

São Paulo, Museu de Arte de São Paulo, inv./cat.nr. MASP.00187

Photo: Google

cat.no. A1.83

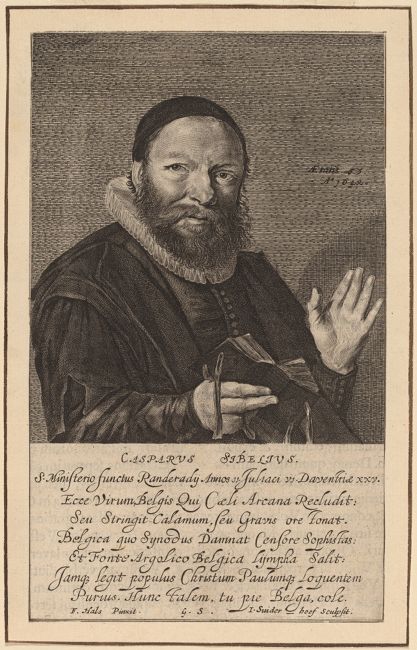

C29 Jonas Suyderhoef, Caspar Sibelius

Copper engraving, 315 x 245 mm, signed lower right: I. Suÿderhoef sculpsit

The Hague, RKD –- Netherlands Institute For Art History

After a lost modello by Frans Hals, on which probably also the painted Portrait of Caspar Sibelius (1590-1658) was based [6]. The text in calligraphic script under the image reads as follows:

‘See the man who reveals heaven’s secrets to the Belgians, be it in writing with his quill, be it speaking as an important orator, whose guiding principle leads the Belgian synod to condemn deceptive theologians and the Belgian wave [the doctrine of faith] springs from the (quickly dwindling) source of Argolis. And we read Christ and Paul in his succession in an unadulterated way. This great Belgian thou, faithful Belgian, must honour’.13

Caspar Sibelius came from the German town of Elberfeld. He finished his studies in theology in Leiden by 1609 and subsequently became a Reformed preacher for various German and Netherlandish communities. Some ten years later, he was sent to the Overijssel synod, where he was chosen to represent the province of Overijssel at the national synod in Dordrecht. In 1634/1635 he took part in the revision of the Dutch translation of the New Testament. His hand-written autobiography is preserved in the municipal library of Deventer.

C29

6

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Caspar Sibelius, 1637

panel, oil paint, 26.5 x 22.5 cm

center right: ÆTAT SVÆ 47 / AN° 1637 / FH<br>formerly New York, private collection

cat.no. A4.1.12

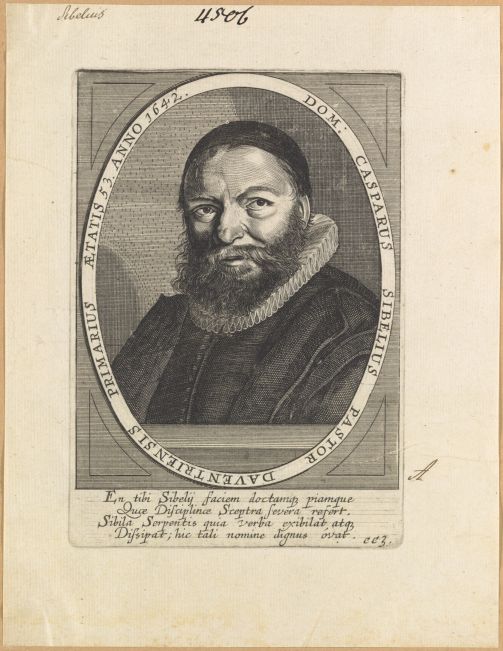

C30 Jonas Suyderhoef, Portrait of Caspar Sibelius, 1642

Copper engraving, dimensions unknown, signed lower right: I. Suyder-hoef Sculpsit. Dated upper right: A⁰ 1642

Washington D.C., National Gallery of Art, inv.no. 1943.3.8085

After a lost modello by Frans Hals, probably via Jonas Suyderhoef’s (1614-1686) earlier engraving of the same sitter (C29). The inscription beneath the portrait carries the same meaning as the text under the earlier print, yet is phrased slightly differently.

C30

Photo courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

C30a Clemens Ammon, Portrait of Caspar Sibelius, c. 165014

Engraving, 143 x 99 mm

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History

Clemens Ammon (*1627) probably used the second print by Jonas Suyderhoef (1614-1686) as the point of departure for this print, since both bear the same date and age of the sitter. In turn, the engraving functioned as the example for a drawing by Jan Stolker (1724-1785) (D47).

C30a

Notes

1 ‘Non opus artificis scalpro pictisve tabellis;/ AmpsingI nescit publica fama mori./ Vivit in Ausonij percusso Praesulis oro./ Ho’u quot in Hispana stigmata fronte leges!/ Draconem. pia turba. tuum quid quaeris in aere.-/ Testentur melius laesa tot ora virum./ Plaga recons: non dum coijt manifesta cicatrix:/ Et nota, si coëant vulnera. dentis erit’.

2 ‘O Haerlem! Ziet hier AMPSINGS wezen,/ Die syne STAD ons geeft to lezen;/ Een HARDER, trou voor Godes Kerk,/ En vaerdig in des Heeren werk;/ Wiens heyl’ge RYMEN en GEDICHTEN/ In wak’ren ernst de vromen frichten:/ Met recht van yder Haarlems kind,/ En van des Heeren volk bemind’.

3 Van Thiel 1996, p. 199.

4 New York 2011, p. 40.

5 Hollstein 1949-2010, vol. 28 (1984), no. 96, p. 242.

6 ‘Dit is die vanden BROECK, die Parssen deed‘ verwondren,/ Doen eerst den Batauier op’t Roode meyr quam dondren/ Die by den Arabier en Indus vaste land./ De eerst voor ‘t Hollants volck den handel heeft geplant’.

7 Conran/Rees Jones 1958, p 239. Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 260.

8 ‘Hier siet ghij PIETER BOR naer t’leven wtgebeelt./ Nae dat hij met sijn pen heeft Scriftelyck gespeelt:/ En nu Aenhoort wat dat gij prijsen wilt of laecken,/ Die waerheijt scrijft: die cant elck een van pas niet maecken’.

9 Oil on panel, 24 x 20.5 cm, monogrammed on the right and inscribed on the oval frame Aeta. 75 Ano 1634 (Rotterdam 1849, p. 17, no. 93, as measuring 22 x 18 cm; Slive 1970-174, vol. 3, p. 120-121, no. L11-3).

10 Jacob Matham, Portrait of Pieter Christiaansz. Bor, 1625, engraving, 256 x 169 mm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. RP-P-OB-27.282X; Jan van de Velde, Portrait of Pieter Christiaansz. Bor, 1631, engraving, 242 x 158 mm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. RP-P-1898-A-2020.

11 ‘Veruolcht van Haet en nijt, vooruluchte hij tot d’eer bij Keijser, koning, Heer. / En won haer gonst met dienst, Slants Staaten hem betrouden, wiens liefd‘ eens weer verkoude,/ Als hem de nijt belaagd, om stutten synen loop gesterct van Godt in Hoop. / Erlangd hy meerder gonst, by ’t grootste Hooft der Gotten, dies hij de nijt bespotten./ Geadelt en verrijct, vernoucht nu sijn gemoet en wacht na d‘ eeuwich goet’. With ‘commander of the Goths’ is referred to the Swedish King Gustav II Adolf (1594-1632), who had ennobled Massa in 1625.

12 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 58.

13 ‘S.S. Ministerio functus Randeradii Annos ii Juliaci vi. Daventriæ xx./ Ecce Virum Belgis qui cæli arcana Recludit: / Seu stringit calamum, Seu gravis ore tonat. // Belgica quo Synodus damnat Censore Sophistas: / Belgicaque Argolicis fontibus unda salit: / Et pure Legimus Christum Paulumque Loquentes. / Hunc talem Belgam, tu pie Belga, cole’.

14 Used as an illustration in J.J. Boissard, Bibliotheca chalcographica, 1650-1654, Frankfurt/Heidelberg, vol. 7 (1650).