1.11 Representing movement

A few years after the Merrymakers at Shrovetide, Frans Hals created another large scale painting with a rich iconographical program – also for an unknown patron and also kept at the Metropolitan Museum of Art today: Young man and woman in an inn [123]. The subject is the Parable of the Prodigal Son, a cautionary tale about man’s seducible nature, ubiquitous at the time through sermons, and disseminated widely by engravings and paintings. The New York painting marks the intersection of several pictorial traditions and stylistic approaches. Wilhelm Valentiner (1880-1958) noted that it could be identical with the large picture of the Prodigal Son listed in 1646 as owned by Cornelia van Lemens, and in 1647 as owned by Martin van der Broeck in Amsterdam, valued at 48 guilders.1 This was a substantial price in Hals’s lifetime. After all, the commission in 1634 for the life-size and full-length portraits of the Amsterdam guardsmen of the Meagre Company (A2.11) stipulated a payment of 60 guilders per sitter.

Hals’s painting depicts a fashionably dressed young man and a young woman in an equally expensive outfit, and captures the gaiety of these individuals as a beacon of vitality. Still, the details within the scene convey a moral message that goes beyond the representation of just a merry moment. The motif goes back to a 1597 engraving by Gillis van Breen († c. 1602/1612) after a design by Karel van Mander (1548-1606), depicting a tavern setting with the prodigal son, seated between two flirting women and with two dogs jumping up to him [124]. The inscription reads: ‘The nuzzle of dogs, the love of whores, the hospitality of inn-keepers: enjoying these does not come without a cost’.2 Since Hals trained with Van Mander, he must have known the engraving. Yet more importantly, the painting’s patron knew the print and its associated moral message, and wished to have these represented.

123

Frans Hals (I) and workshop

Young man and woman in an inn, 1623

canvas, oil paint, 105.4 x 79.4 cm

upper right: FHALS 1623

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv.no. 14.40.602

cat.no. A3.3

124

Gillis van Breen (I) after design of Karel van Mander (I)

Rich man with two prostitutes, dated 1597

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1887-A-11999

125

Detail of fig. 123

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Young man and woman in an inn, 1623

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

126

Detail of: Dirck Hals

Elegant company drinking in an interior, 1627

Berlin, Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Extracting an impression of the nature of an individual’s soul and state of mind from the observation of liveliness and typical movements in a face, body emerges as Frans Hals’s personal pictorial philosophy and skill of representation. Many of his depictions – the figures in the genre-scenes in particular – seem to trace the impulses which become visible first of all in the face, before activating arms and hands. A composition like Young man and woman in an inn displays a virtual explosion of temperament, starting as a burst of laughter in the young man’s face and then striking his limbs. The infectious laughter caught by his lover is emphasized in the composition in the glide of her arm and the direction of her extended hand, which continue the diagonal movement of the man’s arm. Such an interplay is expressed in the medical knowledge of the time, for example in the idea of ‘[…] the animal spirits, which are like […] a very pure and vivid flame which, continually ascending in great abundance from the heart to the brain, thence penetrates through the nerves into the muscles, and gives motion to all the members […]’.3 Therefore, ‘one has to conceive (…) that the motive force, or the nerves themselves, derive their origin from the brain, in which the fantasy is located, by which fantasy the nerves are moved in different ways […]. This example also shows how the fantasy can be the cause of many movements in the nerves […]’.4 These passages express a similar conviction as from the perspective of Hals, that the essence of a human being cannot be found in a recording of the individual’s frozen appearance, or one or the other aspect of his facial features, but rather in moving tension and spontaneous body movement. Man’s soul as the steering mechanism provided by God finds its expression in the emotions which have an impact on the movement of the body. The exuberant young beau raising a wine-glass and sharing his joy with an affectionate girl demonstrates a devotion to the senses: sight, touch, smell, and taste – the food brought by the innkeeper, the wine, the proximity of the girl – just like the dog’s sniffing and snuggling up. The spirited movement and exuberant sensual joy in the two protagonists are vividly observed and brought up-close in a suggestive way. Such a feast for the eyes was certainly not agreed to be the message of the painting. Rather, it was intended as a warning against the basic nature of the senses. The candlestick on the mantelpiece holds a burnt down candle, alluding to the fading of emotions, and indeed of all earthly existence. Beneath, a board is attached holding an ink pot with a quill – or is it a piece of chalk which the innkeeper needs to keep tab of drinks? [125] It is surprising that these less than original motifs were later faithfully quoted in paintings by Dirck Hals (1591-1656), in which also the foreground is merry and the background devout [126].5

The bold structure and the composition consisting of numerous parallel diagonals of the New York painting are typical inventions by Hals. The laughing faces and the gestures seem to be connected by a spontaneous impulse of movement. Even though this is an ambitious commissioned work, the execution of many details in Young man and woman in an inn is less careful than in the Lute player in the Louvre (A1.15) [127] [128]. That piece was painted soon after the New York painting and depicts the same model as its protagonist. However, its clear style of painting is lacking in Young man and woman in an inn. If we begin by inspecting the composition’s various areas, starting from the right hand edge, it becomes obvious that the background with the mantlepiece does not conform to Hals’s accentuating approach, and neither does the figure of the innkeeper with the somewhat clumsily modelled bowl [129]. These parts were executed by the workshop and left unrefined. The head of the dog in the lower right corner is also carried out in a heavy-handed manner.6 Also lacking in inspiration is the execution of the long thin fingers under the dog’s head, which match the equally smooth fingers of the young woman on the shoulder of her beau [130] [131]. Continuing to her other hand and her laughing face, we can observe a design that is certainly by Frans Hals, even though the hard painterly execution is not and rather imitates his paint application. In this passage, the artist has modelled the face using ‘floating reflections’ and hard shadow edges, which results in coarse facial features [132]. These differences in painterly style can be observed well when compared to a female face that is fully painted by Hals himself during the same time, and bearing a similar message about restraining sensual pleasures [133] (A1.14). Neither the blue feather from the man’s hat nor the woman’s hair, her collar, or her cuffs display Hals’s brushwork. The only explanation for their visual appearance and the different lighting directions in the two faces would be the existence of individual preparatory studies by Hals which were transferred onto the painting in a slightly coarse manner. The ‘Halsian’ character of the motif is present, but as it were second-hand. A similar study, made directly in front of the sitter, must have existed for the face of the young man. The observation of a burst of laughter requires special concentration. While Hals’s artistic skill lay in capturing such brief moments, the sitter would have needed to maintain the same head posture while stimulated to laugh repeatedly until all involved facial features had been captured. For this purpose, the wit of the painter would not have been sufficient. A talented jester could conceivably have been consulted for producing such a short and pronounced emotion. For the less extravagant smile of the lute player in the Louvre picture, the process of observation and decisive recording would have been more straightforward.

127

Detail of fig. 123

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Young man and woman in an inn, 1623

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

128

Detail of cat.no. A1.15

Frans Hals (I)

Lute player, c. 1624

Paris, Musée du Louvre

© 2018 RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Mathieu Rabeau

129

Detail of fig. 123

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Young man and woman in an inn, 1623

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

130

Detail of fig. 123

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Young man and woman in an inn, 1623

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

131

Detail of fig. 123

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Young man and woman in an inn, 1623

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

132

Detail of fig. 123

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Young man and woman in an inn, 1623

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

133

Detail of cat.no. A1.14

Frans Hals (I)

Young woman holding a glass and a flagon, c. 1623

Zürich, David Koetser

In the present painting, Hals’s model is perceptible, but the individual accents of the brush are hard and not integrated into the underlying paint layers. Certainly, some later interventions are noticeable, such as the brush swipes on the forehead towards the hair, and of strands of hair above the ears, as well as the lines scratched into the hair with the handle of the brush. All in all, nearly the entire painted surface of Young man and woman in an inn is created in a painting style adapted to Hals, yet still distinctive. This somewhat coarse handling can be found in the clothing, the collar and cuffs; but there is one striking exception: the area of the left hand with the wine glass, which is disproportionately large in comparison to the head [134]. The hand and glass are rendered with loose brushwork, even though the hand with the spread fingers is anatomically complex and challenging to model in the lateral lighting. Only the master painted so elegantly. But why did he reserve this area for himself? The reason cannot be that he attached general importance to the protagonist’s hand and its expression. If we juxtapose the hands of the main figures in Merrymakers at Shrovetide (A3.1) [135] and Young man and woman in an inn (A3.3) [134], a stark difference becomes apparent at one glance. The former is modelled in uniform creamily applied strokes, without a sense of the anatomy of the fingers or clear gradations of light, resulting in the appearance of a boneless rubber hand. There is only one explanation for the special treatment of the hand in the New York painting, which is a particular interest by Hals in the hand as a means of expression. He must have regarded the finger movements in their respective positions and turns toward the light as an authentic object for the observation of genuine spontaneous action.

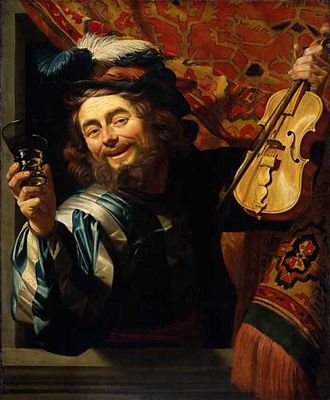

The potential for psychological and aesthetic experience in such a motif would have been demonstrated by the Utrecht painters who were captivated by the dramatic scenes created by Caravaggio (1571-1610) and his followers, which they imitated and emulated. The play with luminosity and color nuances in the hand in Young man and woman in an inn, but also the modelling gradations in individual depictions of finger movement, bring Hals’s work on this hand close to the representations of hands and fingers by Gerard van Honthorst (1592-1656), who had returned to Utrecht from Italy in 1620 and ran his workshop there ever since. There are two paintings by Honthorst which could have been direct models for Hals, both dated 1623: The concert and the Merry fiddler [136] [137]. Both offer spontaneous snapshots of unusual aspects of body movement and facial expression. Probably, the Merry fiddler, with its diagonal structuring and the arm stretched out far into the top right corner of the picture plane, was the essential source of inspiration for Hals’s Young man and woman in an inn. As with Hals, Honthorst’s figure is a laughing reveler in an actor’s costume and a feathered hat. The hand so prominently displayed would thus have been a particularly plausible everyday element of the pictorial motif [138] [139].

134

Detail of fig. 123

Frans Hals (I)

Young man and woman in an inn, 1623

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

135

Detail of cat.no. A3.1

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Merrymakers at Shrovetide, c. 1616-1617

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

136

Gerard van Honthorst

The Concert, dated 1623

Washington (D.C.), National Gallery of Art (Washington), inv./cat.nr. 2013.38.1

137

Gerard van Honthorst

The merry fiddler, dated 1623

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. SK-A- 180

138

Detail of fig. 136

Gerard van Honthorst

The concert, 1623

Washington, National Gallery of Art

139

Detail of fig. 137

Gerard van Honthorst

The merry fiddler, 1623

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

Traveling from Haarlem to Utrecht was nothing unusual in the time of Hals, yet the effort of covering more than 60 kilometers on the road, or indeed spending two days on traveling, would have required substantial reasons. For mere curiosity about the work of fellow painters, Hals could have been satisfied by staying in Haarlem or visiting Amsterdam. Traveling to studios further afield was either prompted by patrons or by practical motives such as sourcing painting materials which were unobtainable elsewhere, or the recruitment of assistants. In Haarlem there were several links to the Catholic-influenced episcopal city of Utrecht and to the group of artists that were trained in Rome and influenced by the work of Caravaggio. The closest connection was the engraver and publisher Jacob Matham (1571-1631), who had made several engravings after inventions by Abraham Bloemaert (1566-1651), the important Utrecht painter and teacher of Honthorst. By 1622, there was already an example of a Caravaggist painting in Haarlem: The supper at Emmaus, painted by Abraham Bloemaert for the secret Catholic station St. Bernardus in Den Hoek.7 Additionally, a genre painting by Honthorst, dated 1624, was engraved by Theodor Matham (c. 1605/1606-1676) some years later, and between 1618 and c. 1640 Jacob and his sons Adriaen and Theodor would create a whole series of engravings after models by Hals (C3, C24, C26, C27, C36).8 Furthermore, Adriaen Matham (c. 1599-1660) would become godfather for Hals’s daughter Susanna in 1634.

Just how much Hals was able to learn in 1623 from the highly successful Gerard van Honthorst becomes clear in a juxtaposition of the two merry drinkers from Young man and woman in an inn and The merry fiddler [140] [141]. The similarities go as far as the blue and white color scheme, the blue feather on the hat and the laughing face with an open mouth. Honthorst has precisely observed the effect of lighting on the changing luminosity of the surfaces and in the gradation of skin tones and fabric shades. In Hals’s painting the gradation of color and light transition has not yet been fully developed and this comparison illustrates why Honthorst was so admired and which elements of his style made such an impression on Hals. Nonetheless, Hals avoided the impression of metallic rigidity which is conveyed in the perfectly captured figures of the Utrecht painters – as must have been observed over a length of time by the artists. He was aware of the contradiction between an ever more convincing representation of typical spontaneous movement and the experience of transitoriness in such impressions. Therefore, he implemented the narrow, close-up view from the Utrecht half-length figure paintings, as well as the dynamic movements in foreshortened perspective which correspond to a momentary perception. He also adopted the emphasis on the light and shadow tones that stand out from the mere pictorial recording of the figure in lateral lighting, and which contrasts attractively with the objective perception of the object. Still, he characterized the arbitrariness and fleetingness of such impressions. Hals emphasized cast shadows and other merely optical appearances of the visual image with his brushwork, which applied one area of color after the next while always ending in soft transitions.

140

Detail of fig. 137

Gerard van Honthorst

The merry fiddler, 1623

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

141

Detail of fig. 123

Frans Hals (I) and workshop

Young man and woman in an inn, 1623

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

142

Dirck van Baburen

Violin player with a wine glass, dated 1623

Cleveland (Ohio), The Cleveland Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 2018.25

143

Gerard van Honthorst

Merry violinist with a glass of wine, c. 1624

Madrid (city, Spain), Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, inv./cat.nr. 194 (1986.21)

© Fundación Collección Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

144

Frans Hals (I)

The merry lute player, c. 1625-1626

London (England), Guildhall Art Gallery, inv./cat.nr. 3725

cat.no. A1.26

145

Gerard van Honthorst

Singing flute player, dated 1623

Schwerin, Staatliches Museum Schwerin, inv./cat.nr. G 25

All hand gestures in Hals’s genre paintings from 1623 onwards can be traced back to the work of the Utrecht painters [142] [143][144]. This does not mean that Hals must have made sketches in front of precisely the pictures we know now, but that he probably copied after some of them and after similar details in contemporary works that are no longer extant. Another work by Honthorst from 1623 can be considered as a possible model for Hals: Singing flute player in Schwerin [145]. Just as the Merry violinist with a glass of wine of c. 1624, this painting is characterized by the psychological observation of expressive moments, with the hand movement in strongly emphasized contrast supporting the facial expression [146] [147][148]. A mental dimension becomes apparent in emotional movement. This Utrecht-based pictorial arrangement can be found again in the genre paintings in which Hals experimented with new possibilities. Indirectly, the refined observation of light can also be observed in his portraits, especially in the group portraits of 1626-1627 [149] (A2.8A). Additionally, the hand of Honthorst’s Merry violinist with a glass of wine, turned clockwise 45 degrees, is depicted again by Hals as the hand of captain Michiel de Wael (1596-1659) pouring out his glass to the final drop in the Banquet of the officers of the St George civic guard. Close comparison of both details clearly shows how Hals was able to transfer a momentary observation onto the canvas by means of his characteristic sketchy brushwork [150] [151].

146

Detail of fig. 145

Gerard van Honthorst

Singing flute player, 1623

Schwerin, Staatliches Museum Schwerin

147

Detail of fig. 143

Gerard van Honthorst

Merry violinist with a glass of wine, c. 1624

Madrid, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza

148

Detail of fig. 144

Frans Hals (I)

The merry lute player, c. 1625-1626

London, Harold Samuel Collection

149

Frans Hals (I)

Banquet of the officers of the Saint George civic guard, c. 1626-1627

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv./cat.nr. OS I-110

cat.no. A1.30

150

Detail of fig. 143, rotated

Gerard van Honthorst

Merry violinist with a glass of wine, c. 1624

Madrid, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza

151

Detail of fig. 149

Frans Hals (I)

Banquet of the officers of the St George civic guard, c. 1626-1627

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

Notes

1 Valentiner 1923, p. 307. For the archival records of the 1646 list of goods of Cornelia Lemens and the 1647 sale of goods from Van den Broeck to Andries Ackersloot, see inv.no. 549 and 566 in The Montias Database of 17th Century Dutch Art Inventories.

2 ‘Honden gonst hoeren lieft weerden gastvrien / Sonder cost gheniett ghy niet een van drien’.

3 Descartes 1850, p. 96 (English translation of Descartes 1637).

4 Descartes/Hefferman 1998, p. 145.

5 See also: Dirck Hals, Elegant company smoking and drinking in an interior, oil on panel, 34 x 65 cm, Schwerte, private collection.

6 Slive noted the origin of this motif in an engraving from c. 1595: Jan Saenredam, Man and woman with flowers: Smell, engraving, 173 x 123 mm, London, British Museum, inv. no. 1874,0711.1862. Slive 1970-1974, vol. 2, p. 73, 78.

7 Abraham Bloemaert, The supper at Emmaus, 1622, oil on panel, 145 x 215.5 cm, Brussels, Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten van België, inv. no. 3705.

8 Theodor Matham, Laughing violinist holding a flute glass, 1627, engraving, 210 x 159 mm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, inv. no. RP-P-BI-551X.