1.13 Prints made after the master’s design

Hals’s oeuvre is generally appreciated as an achievement in two genres: the creation of formal and informal portraits, that is, representative depictions of persons from the time’s upper class, and portrait-like observations of human figure types from everyday life – the genre scenes. The first were mostly created as private commissions, as painted busts, half-lengths, three-quarter or full-length portraits, of individuals, married couples and families. In addition, there were the large-scale group portraits of officers and sergeants of the civic guards, five from Haarlem and one from Amsterdam. Finally, there are the three group portraits of the regents of the St Elisabeth’s Hospital, and the regents and regentesses of the Old Men’s Almshouse in Haarlem. In contrast, the moralizing and entertaining genre paintings were restricted to small to medium sizes and intended for the open market. A small part of these are creations by Hals alone – like the sketchy and quick momentary observations of children, singers, actors, musicians, or quirky characters such as Verdonck (A1.34), Peeckelhaeringh (A1.50), and Malle Babbe (A1.103). The workshop, however, soon began to create replicas or variants of many of these. In addition, pictures were created by assistants with greater or lesser involvement of the master, in a large number of surprisingly free variants. Many of them bear FH monograms as part of the original paint layer and therefore are undoubtedly original workshop products. There is, however, a third category of output from the Hals workshop that was particularly relevant for public perception: portrait engravings for which Hals created the modelli. With up to 200 prints per copperplate this type of representation reached a broad public – unlike painted portraits which mostly disappeared behind the doors of private residences.

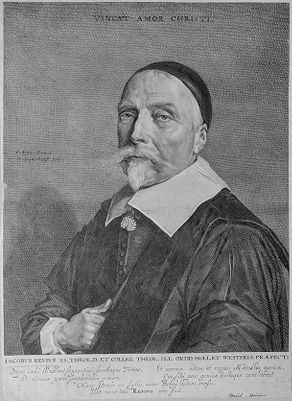

So far, portrait engravings were only regarded as a marginal type of art production, functioning as a sort of placeholder for lost paintings and as testimony of the contemporary appreciation for Hals in the form of reproductions of his paintings. However, that is a modern way of thinking. In the past, it was simply not considered that the production of portrait engravings formed a completely independent artistic activity. The almost overwhelming quality of many engravings was not taken into consideration, and neither were the inscriptions which often ranked the abilities of the engraver higher than the skill of the painter. For example, the inscription beneath the portrait of Conradus Viëtor (1588-1657) from 1657 (C40) reads: ‘The engraver gives us this image of him whom God gave his character / Viëtor, great spirit: not sufficiently praised on earth’.1 Based on today’s concept of Modernism, we attribute greater praise to the painter as the intense observer and original creator, even though our appreciation is limited to values of psychology and aesthetics. Yet Frans Hals could clearly live with the limited appreciation of his talent, as can be seen in the example of his portrait of Jacobus Revius (1586-1658) [187]. This engraving – based on Hals’s design – was distributed widely, and was initially not even signed with his name. In the first state, the inscription reads A. V. Dyk. Pinsit, suggesting that the prolific Flemish artist Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641) had painted the modello.2 In the second state this was corrected to F. Hals Pinsit. This error shows that for Hals’s contemporaries, interest in the sitter was paramount, and the identity of the portrait’s creator was only secondary. In turn, the engraver and publisher of a print were at least as important as the portraitist who delivered the design. This explains the fact that the portrait of the prominent theologian Johannes Hoornbeeck (1617-1666) (C45) is only inscribed I. Suijderhoef sculps. and Pieter Goos excudit, whilst no reference to Frans Hals can be found. The later copy by Jan Brouwer (c. 1626-after 1688) neither bears any reference to Frans Hals.3

Jacobus Revius, eternalized in the engraving by Jonas Suyderhoef (1614-1686), after Hals’s design, was a combative Calvinist theologian, preacher, poet, and historian. Through his poems he reached a wide public, in some church hymns even up to the present. It is tempting to draw a connection between the mirthless, slightly pinched expression of the sitter and the eulogy underneath the portrait which was written by the important Leiden scholar Daniel Heinsius (1580-1655):

‘Whom heavenly wisdom and holy virtue grace,

And the pure love of simplicity,

And the splendor of morals like the command of prudent behavior,

And to whom talent was given as well as scholarly endeavor to express himself,

Be it in Greek, be it in Latin and now in Netherlandish verses,

This was my Revius’.4

This enthusiastic eulogy may sound unreal to us, but together with the time-consuming and expensive effort of engraving and printing and the expense for the painter, it does convey something of the aspiration of the medium of portrait engraving, which reached an unsurpassed level especially in Haarlem in the 16th and 17th centuries. This was a qualified form of image transmission over great distances and with considerable reach. To find suitable modelli, engravers did not require portraits on canvas or panel. Rather, oil sketches on paper were sufficient, as they were cheaper to make and dried more quickly. These designs could be traced from the front or back and used as models both for the transfer to a copperplate as well as for painted portraits. The models did not need to be finished into every detail, or created by one single hand. For the present engraving, the too short left arm appears as an afterthought, with an atypical execution. This means that the face and shoulder areas were executed by Hals himself [188], while the arm and hand were created by assistants – either based on a general sketch by the master or even without it. But it is also conceivable that such an area was added by the engraver on request of the patron. Most of the modelli have not survived, because they were fragile, and got damaged and worn through use. In Hals’s case, a single execution on paper still exists which was probably such a modello: the portrait of the preacher Theodor Wickenburg († 1655) (A4.1.17). However, this portrait and the engraving created on the basis of it belong to a group of artworks that cannot be attributed to Frans Hals himself, but rather to his main assistant of the later period, most likely his son Frans Hals II (1618-1669).

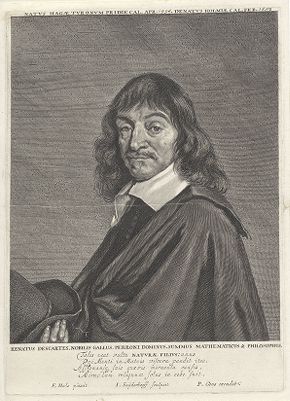

Whether an engraving merely reproduced an already existing painting or whether it was an original creation for which suitable modelli first had to be produced, is difficult to determine in retrospect. One can only try to determine this if both a painted and engraved version of the same scene exits, and if one is artistically superior to the other. A case in point is the portrait of René Descartes (1596-1650). Its painted variant exists in many versions and sizes, with the most frequently reproduced ones being the small panel in Copenhagen [189] and the much larger canvas in the Louvre in Paris [190]. Jonas Suyderhoef’s engraving of Descartes [191], with the thoughtful and even scrutinizing expression and wearily raised eyebrows captured in subtle transitions, conveys an observation focused on the area of the eyes. At the same time, delicate details, such as the hair above the left jawline are meticulously depicted. Based on this sensitive creation, it is understandable that Hals’s design was preferred over other known portraits of Descartes, was much copied, and was also reproduced in the medal commemorating the philosopher’s death, created c. 1685.5 Out of all painted versions, the one in the Louvre is closest to the engraving. It depicts the face of the sitter in consistent proportions and includes incidental details like the wart on the illuminated cheek. The mouth is somewhat broader in the painting, and all facial features appear flatter. Additionally, the eyes stare slightly upwards, whereas in the print, the sitter has directed his piercing gaze towards the sitter [192] [193]. Even though of the numerous variants the Louvre painting may be closest to Hals’s initial design, it features narrowly drawn lines instead of the master’s subtle brushstrokes. The fact that previous literature refers to the Copenhagen version as being an original by Hals is not borne out by close observation. This portrait only represents part of what is depicted in the other ones, and its execution differs from Hals’s autograph technique. It is technically impossible to derive a facial expression that is so subtle in every detail as in Suyderhoef’s engraving from the coarse model of the small Copenhagen picture [194].6

It is not known who commissioned the portrait of Descartes. Slive noted that a source from 1691 mentions that the Haarlem clergyman Augustinus Bloemaert (1585-1659) had expressed a desire for a portrait of Descartes – most portraits of scholars at the time were engravings. But Slive’s further reference to the Leiden publisher Jan Maire (c. 1575-1666) may also be correct, as the latter had published Descartes‘ Discours de la Méthode in 1637.7 There were many links between Leiden and Haarlem, and in the case of a print commission, the engraver would have been the main point of contact, since he had to allow for most of the time needed. In any case, demand for such an engraving would have been great enough for a profitable engagement of engravers and painters. Steven Nadler recently summarized the sources on the date of the meeting between Hals and Descartes: ‘The painting was made sometime that summer [of 1649, ed.], perhaps as late as September, when Descartes finally embarked for Sweden. It must have been done before Descartes went to Amsterdam to settle some affairs and board the ship to Stockholm (…). So if the painting is from life and Descartes did pose for Hals, in all likelihood it was done in Haarlem when Descartes’s final departure from Egmont was imminent’.8 Descartes’ forthcoming departure from the Low Countries in September 1649 certainly allowed only a brief period of time for sittings, which also suggests a medium on paper as the most practical and versatile. The fact that the engraving was only ready to be printed in the course of 1650 does not rule out a project aimed at an engraving and several painted copies.9

The example of the Descartes portraits commands the greatest respect for the abilities of the engraver, who undertook a representation of a sitter into a different medium and who achieved a highly expressive rendering on the basis of the now lost modello by Frans Hals. The same applies to the head in the portrait of Jacobus Revius (C47). In both prints, the black and white rendering reveals such a confident prior execution that the engraver must have seen it directly. Yet like the Revius print, the Descartes engraving displays a weak spot which was certainly not part of the master’s precisely executed design: the hand in the lower left corner. What may have been sketched in Hals’s modello with two or three brushstrokes has become a meticulously detailed area in the engravings and the painted variants of the Descartes portrait [195] [196]. The Copenhagen version copy also displays these intently marked fingertips.

187

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of Jacobus Revius (1586-1658), c. 1650

The Hague, RKD – Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis (Collectie Iconografisch Bureau)

cat.no. C47

188

Detail of fig. 187, reversed

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of Jacbous Revius, c. 1650

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History

189

workshop of Frans Hals (I) or after Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes, c. 1649

panel, oil paint, 19 x 14 cm

Copenhagen, SMK – National Gallery of Denmark, inv.no. DEP7

cat.no. A4.1.15a

190

workshop of Frans Hals (I) or after Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes, c. 1649

canvas, oil paint, 76 x 68 cm

Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv.no. 1317

©2016 RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/ Tony Querrec

cat.no. A4.1.15

191

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of René Descartes (1596-1650), after February 1650

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-60.718

cat.no. C46

192

Detail of fig. 191, reversed

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of René Descartes, after February 1650

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

193

Detail of fig. 190

workshop of Frans Hals (I) or after Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes, c. 1649

Paris, Musée du Louvre

©2016 RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/ Tony Querrec

194

Detail of fig. 189

workshop of Frans Hals (I) or after Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes, c. 1649

Copenhagen, SMK – National Gallery of Denmark

195

Detail of fig. 191, reversed

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of René Descartes, after February 1650

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

196

Detail of fig. 190

workshop of Frans Hals (I) or after Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes, c. 1649

Paris, Musée du Louvre

©2016 RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/ Tony Querrec

Notes

1 ‘Den prenter geeft dit beelt, van die dien God gaf t’wesen/ VIETOR groote Geest: op aerden noijt vol presen:’. See the catalogue entry on cat.no. C40 for the full inscription and translation.

2 Jonas Suyderhoef, Portrait of Jacobus Revius, engraving, c. 325 x 230 mm, Vienna, Graphische Sammlung Albertina, inv.no. H/I/61/26.

3 Jan Brouwer, Portrait of Johannes Hoornbeeck, engraving, 320 x 255 mm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-P-1907-3000.

4 ‘Quem coeli illustrat sapientia, sanctaque Virtus,/ Et niveus purae simplicitatis amor, / Et morum nitor, et regina Modestia morum, / Cui sibi par. genius doctaque cura dedit / Nunc Graio ac Latio, nunc Belga ludere versu./ Ille meus tali REVIUS ore fuit’.

5 Jan Smeltzing, Medal commemorating the decease of René Descartes, silver, ø 4.8 cm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. NG-VG-1-836.

6 Tracing dots can be discerned in the contours of the upper eyelid, the nostril and the chin. It would be worthwhile to investigate these through infrared photography.

7 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 314. For the possible commission by Bloemaert, see also: Nadler 2013, p. 181-195.

8 See: Nadler 2013, p. 181, 186, 189-190, 191. The quote is from p. 189-190.

9 Descartes died in Stockholm on 11 February 1650; the upper edge of the engraving notes the sitter’s life dates.