1.15 A presumably more expensive commission

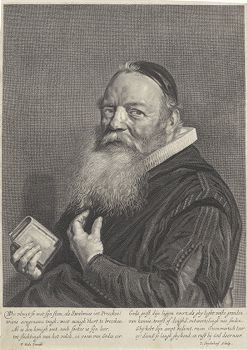

At the same time as the small portraits of the Scriverius couple (A4.1.4, A4.1.5), in 1626, Frans Hals painted half-length representations of the preacher Michiel Jansz. van Middelhoven (1562-1638) [208] and his wife Sara Andriesdr. Hessix [209]. The most likely occasion would be the couple’s 40th wedding anniversary. In both cases it was Jan van de Velde (1593-1641) who made an engraving after the male portrait [210]. The social positions of the clergyman from Voorschoten and the independent scholar from Haarlem were comparable. However, Petrus Scriverius (1576-1660) was a wealthy man and Middelhoven probably was not, if we believe the Latin text in the engraving under his portrait. In translation, it reads:

‘Bringing Christ closer to his people over 33 years

And a happy father to 7 pairs of children

With this august pleiade of muses,

you cannot live on your stipend,

but through your learned descendants’.1

The latter phrase refers to the seven sons from the Middelhoven-Hessix marriage, who all became preachers a well. Apart from this difference in wealth, there seems to have been a major contradictory difference in the portrait commissions of both couples, since Scriverius and Van der Aar only received the abovementioned small workshop-paintings, whereas the couple Middelhoven-Hessix received two life-size half-length portraits, fully executed by the master himself.2 Though we do not know any financial details of the contract in this case, as in most others, it stands to reason to assume the amount of remuneration was decisive for the level of Hals’s involvement.

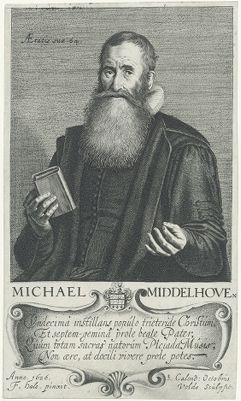

210

Jan van de Velde (II)

Portrait of Michiel Jansz. van Middelhoven (1562-1638), dated 3 October 1626

Paris, Fondation Custodia - Collection Frits Lugt, inv./cat.nr. 3260

cat.no. C10

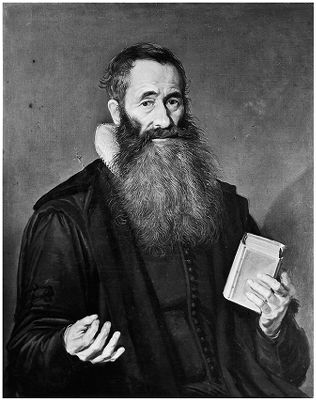

208

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Michiel Jansz. van Middelhoven (1562-1638), 1626

Paris, private collection Adolphe Schloss

cat.no. A1.27

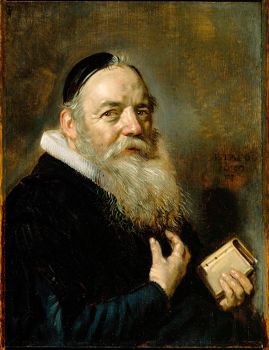

209

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Sara Andriesdr. Hessix, 1626

Lisbon, Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, inv./cat.nr. 214

Photo: Catarina Gomes Ferreira

cat.no. A1.28

The abovementioned comparisons between the execution of engravings and paintings can be applied to many other examples. If we review these cases, we become familiar with typical features of a workshop execution after a template. They are most clearly visible in the details which are hard to capture. Giovanni Morelli (1816-1891), the father of methodical connoisseurship, referred to revealing ears and hands, which also proves true here.3 But the issue in the inspection of the small-scale portraits with the monogram FH is not whether these are genuine or false, originals or copies. Instead, it concerns the historical production of pictures under the master’s supervision, which are therefore always genuine. Just how far the historical concept of genuine accomplishments went – signed as such at the time with the monogram FH, with payment made to the master – can be demonstrated in the following example, the portrait of Hendrik Swalmius (1577-1649) in a painting and an engraving [211] [212]. Both have the same size, with the painting being cut at the top and both sides at a later date. Since a pendant of the present picture survives – the Portrait of Judith van Breda [213] – its original size can be deducted. The text below the engraving identifies the sitter as the reformed clergyman Hendrick Swalmius and mentions his 46 years of service. Since he was ordained in Haarlem in 1600, the print could only have been created by 1646 at the earliest, seven years after Hals’s painted portrait, which is dated 1639. If we assume that painted and engraved portraits of clergymen were typically commissioned by their parish or by charitable foundations they worked for, this particular commission would have anticipated the memorial purpose by quite some time. Was the portrait perhaps commissioned due to an illness and out of concern for an impending death, or with view to Swalmius’s 40 years of service in 1640? The answer can only be found in a comparison between painting and engraving. Could Jonas Suyderhoef (1614-1686) have created the surviving copper engraving on the basis of the picture from 1639 – or would he have needed another modello created by Hals?

If we put enlarged details from the engraving and the painting side by side, the facial features and hands in the engraving show such a closely related manner of execution that several conclusions come to mind [214] [215] [216][217]. If the modello for the engraving was executed by an assistant, Hals must have prepared the templates for face and hands. As in the portrait of Jacobus Revius (1586-1658) (C47), a relatively large head seems to have been attached to a narrower body. This montage error can probably be attributed to the workshop. Yet neither Hals nor Suyderhoef intervened. Looking at the decoration and the folds of the dress of Judith van Breda [218], we find the somewhat mechanical work of an assistant – note the flatly applied pattern – which is still rich in detail. The same probably applies to the surface of the dark clothing of Swalmius. In any case, the engraving does show such a detailed execution [219]. In contrast, there are no matching visible traces left in the painting today [220]. The close similarity in other aspects leads to the inevitable conclusion that the delicate grey highlights have lost their opacity and that the thin, fine, brushstrokes on the surface were simply abraded or cleaned off. The same effect can be observed in the curls of the white beard which were actually also rubbed and shortened because of this.

211

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Hendrik Swalmius, 1639

panel, oil paint, 27 x 20 cm

center right: AETAT 60/1639/FH

Detroit Institute of Arts, inv.no. 49.347

cat.no. A4.1.13

212

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of Hendrick Swalmius, after 1639

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-60.768

cat.no. C34

213

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a woman, possibly Judith van Breda, 1639

panel, oil paint, 29.5 x 21 cm

lower left: AETAT 57/1639

Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, inv.no. 2498

cat.no. A4.1.14

214

Detail of fig. 211

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Hendrik Swalmius, 1639

Detroit Institute of Arts

215

Detail of fig. 212

Amsterdam, Rijkmuseum

The print – here cropped and reversed – even reproduces the smallest detail of the painting, such as the facial hair that is rendered in soft, short brushstrokes

216

Detail of fig. 211

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Hendrik Swalmius, 1639

Detroit Institute of Arts

217

Detail of fig. 212, reversed

Amsterdam, Rijkmuseum

218

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a woman, possibly Judith van Breda, 1639

Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen

219

Detail of fig. 212, reversed

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of Hendrick Swalmius, after 1639

Amsterdam, Rijkmuseum

220

Detail of fig. 211

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Hendrik Swalmius, 1639

Detroit Institute of Arts

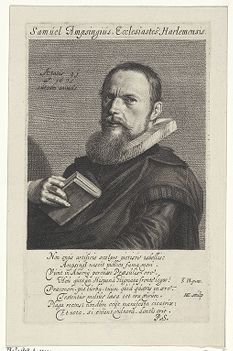

Similarly to the Swalmius print, the 1632 copper engraving by Jan van de Velde [221], depicting Samuel Ampzing (1590-1632) can be compared to the painted portrait from the Hals studio [222], that was traditionally considered its modello. As in the case of Swalmius, both representations of Ampzing are of the exact same size [223], and in the Ampzing painting there are also several areas where a hesitant slashing brushwork leads to question Hals’s involvement on the one hand, and the relation to the engraving on the other. The comparison of the two artworks first results in the conclusion that the painted version must be a cursory imitation after a lost model, and that the 1632 engraving of the same size is a more precise one. This assessment is confirmed by a glance at the facial features as well as other details. If we juxtapose random sections of the painting and the print, we find that the engraving always shows a clearer reflection of the model and is also closer to the stylistics of Frans Hals. The zone of the shoulder and upper arm is executed cursorily in the painting [224] [225]. It provides less information about the details of the represented clothing than the much more coherently executed engraving. Indeed, it is possible to create the painting on the basis of the engraving, but not vice versa. Moreover, the transformation of the clothing into an abstract pattern of fields in varying shades of grey, as can be seen in the Portrait of Jean de la Chambre (A1.87), is entirely absent. Nothing can be seen of Hals’s dynamic brushwork in Ampzing’s facial area either [226]. Details like the anatomy of the ear and hand are rendered awkwardly. The manner of painting with its many short strokes differs fundamentally from the style in portraits that are securely attributed to Hals. It lacks the clarity of a characterization laid out in economical brushstrokes as can be seen in the Portrait of Jean de la Chambre [227]. The simplicity and precision of the shape of the eyes, nose, mouth, and ear of the latter differ in their essence from the hesitant descriptive brushwork in the Ampzing portrait. This tentative manner of execution is typical for the work of an assistant or copyist, working from a no longer extant model by Hals. Hals’s painterly approach is entirely different, as is obvious in the De la Chambre portrait. In the master’s prime depiction of Ampzing, the eyes, nose, and ear must have been modelled and drawn with similar precision. Both the extant engraving and painting could thus have been based on this no longer known model.

221

Jan van de Velde (II)

Portrait of Samuel Ampzing, dated 1632

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1898-A-20197

cat.no. C22

222

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Samuel Ampzing, c. 1630-1631

copper, oil paint, 16.4 x 12.4 cm

center right: AETAT 40/AV⁰ 163..

New York, The Leiden Collection, inv.no. FH-100

cat.no. A4.1.9

223

Detail of fig. 221, reversed

Jan van de Velde (II)

Portrait of Samuel Ampzing, 1632

Amsterdam, Rijkmuseum

224

Detail of fig. 222

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Samuel Ampzing, c. 1630-1631

New York, The Leiden Collection

225

Detail of fig. 221, reversed

Jan van de Velde (II)

Portrait of Samuel Ampzing, 1632

Amsterdam, Rijkmuseum

226

Detail of fig. 222

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Samuel Ampzing, c. 1630-1631

New York, The Leiden Collection

227

Detail of cat.no. A1.87

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Jean de la Chambre, 1638

London, National Gallery

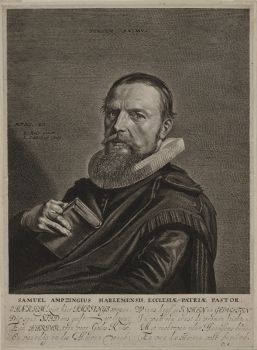

This being said, there exists a second engraving from c. 1640 [228], which is less spirited, but probably closer to Hals’s initial modello, which seems to have still existed when the highly sensitive engraver Jonas Suyderhoef set to work. His engraving matches the extant painted portrait in the motifs, but it measures nearly double in height and width and shows a wider space around the sitter. Suyderhoef must have worked from a detailed design ‘from life’ which was also the basis for the earlier engraving and the painted variant. The differences between the painting and both prints are significant, and as noted above, the former can be excluded as a modello – also for Suyderhoef’s engraving. Nor the shape of the ear, the creases around the eye, the design of the hand, and neither the folds of the coat could have been derived from the respective areas in the painting. While the painting shows an unfocused gaze and a generally more serene facial expression, Suyderhoef’s portrait conveys a questioning-scrutinizing expression through the dominating eyes, which correspond coherently to the vertical creases in the forehead [226] [229] [230]. The painted repetition lacks this psychological clarity and immediacy. It is not possible to derive such a coherent facial expression as depicted in Suyderhoef’s print from the small painted variant, nor could it have been based on an enlargement of Van de Velde’s engraving. The same applies to the hand in Suyderhoef’s print, which is so ‘Halsian’ in the modelling of the fingers [231] [232][233]. In that passage, Suyderhoef proves to be a precise observer of the painted modello, having captured the subtle delicacies in tonality and the characteristic brushwork. Van de Velde’s print testifies of the engraver’s trained sensibility for depicting the anatomy of a hand, even though it is a slightly simplified representation, with a clear emphasis on the three-dimensional volume of the hand and book. The hand holding a book in the painted variant conveys an impression of the original colors of Hals’s design, yet does not feature the master’s clear brushwork. When comparing this with the same section in Van de Velde’s and Suyderhoef’s engravings, it becomes clear that this painting cannot have functioned as the example. Indeed, both artists were excellent engravers, but they were hardly the artistic virtuosos who would have taken it into their own hands to reformulate the extant painted version into a more spirited and coherent representation.

Samuel Ampzing was an important sitter for Frans Hals. He was influential as a combative Calvinist clergyman and also formative beyond his time as a historian and poet. His historical accounts of the siege and Spanish occupation of the brave city of Haarlem remained reference works until the 18th century.4 In his 1621 praise of the city of Haarlem - Het lof der stadt Haerlem in Hollandt – as in the expanded account from 1628 - Beschryvinge ende lof der stadt Haerlem in Hollandt – he was the first author to mention the painter brothers Frans and Dirck Hals (1591-1656). In the first publication, their names are included in a list providing an overview of artists active in Haarlem at the time, of which there were more than fifteen. As Slive noted, Ampzing’s praise in the 1628 version is slightly more emphatic:

‘Forth Halses, come forth,

Take here a seat, yours it is by right.

How dashingly Frans paints people from life!

How neat the little figures Dirck gives us!

Brothers in art, brothers in blood.

Nurtured by the same love of art, by the same mother’.5

Yet these noncommittal words of praise fall well behind when we read the similar and sometimes more outspoken words Ampzing wrote about Hals’s fellow painters, for instance on the comparatively modest achievements of the portrait- and genre-painter Hendrick Pot (1580-1657):

‘And Hendrick Pot must also justly bear his crown.

It is a miracle, what he achieves in these times

With his fine hand’.6

Ampzing died on 29 July 1632. Jan van de Velde’s engraving was probably made on the occasion of his passing. The close chronological connection between the present small-scale painted portrait and the 1632 print, as well as the subsequent creation of another, much larger engraving of Ampzing’s portrait suggest great public interest representations of Samuel Ampzing. The message which his portrait was supposed to convey, is expressed in the eulogies added to the engravings by Van de Velde and Suyderhoef, which were both – following the monogram P.S. below the lines of verse – composed by Petrus Scriverius, who had also been involved in Ampzing’s books on Haarlem. It is of interest that the inscription of the first, small-size engraving was written in Latin, which means that it was delivered to recipients with the necessary education. It includes the phrases ‘Ampzing’s fame (…) cannot die. It lives on in the stricken face of the Ausonian bishop’. and ‘Why, devoted congregation, do you seek to have your Herald pictured on copper? The wounded faces of so many men will bear witness to him’.7 These lines refer to the polemics of the combative Calvinist Ampzing, which were expressed particularly in his controversial theological pamphlets.

Ampzing was a preacher at Haarlem’s main church of St Bavo. Its parish councilors were responsible for the commission of the engraving, an intention they had probably already pursued when ordering a portrait modello from Frans Hals. It is hard to understand why almost a decade later an engraving of nearly twice the size was commissioned from Jonas Suyderhoef. The inscription under this print is written in Dutch and suggest that the city council of Haarlem probably arranged for this ambitious second edition:

‘O Haarlem, look upon Ampzing’s appearance,

Which his city gives us that we may know him:

A shepherd true to the church of God,

And proficient in the Lord’s work,

Whose edifying verses and poetry uplift the pious with their deep gravity;

Rightly is he beloved of all Haarlem’s children and of the Lord’s people’.8

The painted likeness of Ampzing was painted on copper and therefore forms a durable repetition of the several preparatory drawings and colored sketches on paper that must have been created by Frans Hals. This way of portrait-making was obviously cheaper, as assistants could execute a painting on the same occasion as the engraving was being made, painting a sort of ricordo of the already existing modelli on paper. Copper plates were available time and again in print workshops, after they had been used for printing several times and finally flattened down. While the printed engraving was distributed far and wide, patrons could retain the painted picture as a keepsake. And since the main objective was the representation of the sitter, and the executing painter was secondary, a painting executed by an assistant from the workshop was no sacrilege. Compared to the sketchy designs on cheap material or a portrait on oil-soaked paper covered in pinpoint holes and worn through use, such a portrait was a worthy representation.

228

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of Samuel Ampzing (1590-1632)

The Hague, RKD – Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis (Collectie Iconografisch Bureau)

cat.no. C23

229

Detail of fig. 221, reversed

Jan van de Velde (II)

Portrait of Samuel Ampzing, 1632

Amsterdam, Rijkmuseum

230

Detail of fig. 228, reversed

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of Samuel Ampzing

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History

231

Detail of fig. 228, reversed

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of Samuel Ampzing

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History

232

Detail of fig. 222

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Samuel Ampzing, c. 1630-1631

New York, The Leiden Collection

233

Detail of fig. 221, reversed

Jan van de Velde (II)

Portrait of Samuel Ampzing, 1632

Amsterdam, Rijkmuseum

The meticulous observation of details can also be helpful in explaining the peculiarities appearing in the painted and engraved portraits of Theodorus Schrevelius (1572-1649) [234] [235]. This intellectual, who was important for Hals, had himself portrayed twice, in 1617 by Frans Hals [236] and in 1625 by Pieter de Grebber (c. 1595/1605-1652/1653) [237].9 Since the painting from the Hals workshop has been fragmentarily preserved and Hals’s original modello is only documented through two engravings, the family portrait by De Grebber forms an important source and can assist in better assessing Hals’s representation of Schrevelius. Comparison of the facial features in the extant artworks follows two lines of enquiry: what did Schrevelius look like? And: what was Frans Hals’s share in the documented representations? The likeness of Schrevelius in the 1625 family portrait by De Grebber forms a trustworthy documentation of his appearance. The frontal lighting, the subtle modelling of the face and the rendering of individual details like the auricle confirm the reliability of the portrait. The differences in comparison to the painted portrait of 1617 [238] are substantial: the latter shows a distinctly different ear shape and nose length, as well as an overemphasized nasolabial fold, which is strongly highlighted in by lateral lighting.

As many other examples demonstrate, both Hals and De Grebber were masters of rendering facial proportions, which excludes an explanation of the visible differences in these two portraits as random errors. The excellent engravers Jacob Matham (1571-1631) and Jonas Suyderhoef were equally reliable craftsmen. We must therefore include their engravings of Schrevelius in the comparison. This reveals that the painting from the Hals workshop is closest to the Suyderhoef prints [239]: the facial proportions match precisely, yet essential elements of Suyderhoef’s representation are missing in the painting. If we look at Suyderhoef’s engraving in reverse, we see the composition in the way as he himself had drawn it into the copperplate with his burin. Doing so, he copied a drawn, painted, or printed modello – in fact being one of the most reliable reproduction-engravers of his time. The contours of his engraving match those of the similar-sized painting, but many details were rubbed off or reworked in the latter. The subtle wink of the left eye and the complacent expression formed by the mouth, the slightly raised eyebrows, and part of the creases on the forehead are not identifiable in the painting, as is the small wart next to the left eye. The subtly modelled facial expression in the engraving has disappeared in the painting under later overpainting.

So far, the predominant view was that Hals had created the small-scale painted portrait, on which Matham and Suyderhoef based their engravings. After all, Hals is referenced in both as the painter. Yet Wilhelm Valentiner had already been of the opinion that Matham’s engraving had not been based on the painting.10 Based on the difference between the two engravings, he assumed that there had been a modello by Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617) for the engraving by the latter’s son-in-law Matham. There are indeed many other examples for this collaboration, but in the present case the Mannerist character of Matham’s engraving can be explained sufficiently through its typical tracing of lines – not even taking into account the unequivocal information on the print itself: Fra. Hals pinxit. Nevertheless, the difference between the two engravings is so explicit that the existence of multiple drawn modelli may certainly be assumed. This can be seen in the elongated facial proportions in Matham’s representation, as well as in the shape of the ear, the longer nose, the distance between nose and mouth, and in the modelling of the forehead, the eyes and the cheeks [240]. However, Matham’s representation is not random, but rather closely related to De Grebber’s painting and as such confirms the accuracy of the features. Schrevelius is likely to have looked like this. Moreover, this conclusion gives special relevance to Matham’s print, turning out to be the only surviving document of a lost modello by Frans Hals. The fact that this must have been a finely detailed artwork can be seen in the detail-illustrations of the chest and arm. This area is the best preserved part of the oil painting today – being precisely observed in its three-dimensional appearance – but it must have been even more accurately developed in the original modello. At the same time, the textures of the fabrics and the fur trim are rendered brilliantly, particularly bearing in mind the small format of the picture. A comparison between the engravings and the execution in oil paint results in an unequivocal sequence: it is possible to create the painted version [241] as a simplified and imprecise variant on the basis of Matham’s engraving [242]. But vice versa, it is impossible to generate a coherent presentation of shapes, their surfaces, and lighting. The outcome of making an engraving after the extant painted modello can be seen in Suyderhoef’s engraving [243].

The conclusion we can draw upon these observations, is that Frans Hals created a painted portrait-modello for Jacob Matham’s engraving, whose coloring was probably close to the painting by Pieter de Grebber. When Schrevelius or friends of his were planning another edition of engravings with his portrait by the 1640s, Hals’s original modello was no longer available. It may have been executed on paper or consisted of several individual studies which were not meant to be preserved. However, a same size version in oil had been executed on copper – the majority of small pictures from the Hals workshop was on this support – as a ricordo. This workshop product was less precise than the print by Matham. Once he passed away in 1631 and Jonas Suyderhoef had successfully created some portrait engravings for Hals from 1637 onwards, the latter was also tasked with producing the second run of Schrevelius-engravings. As a modello, there seems to have existed only the small painting on copper, but with freshly reworked details such as the highlights on the nose – identified by restorer Martin Bijl as squashed, not yet dry paint.11 These reworkings were applied to the mischievous-mocking facial expression with the gaze turned towards the viewer, which do not appear in Matham’s 1618. It is impossible to say who executed them, but in any case, Hals’s brushstroke is not apparent. These original additions are unfortunately not preserved and fell victim to later cleanings and reworkings. Nevertheless, Suyderhoef’s engraving has captured them.

234

Detail of cat.no. C3

Jacob Matham

Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius, 1618

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

235

Detail of cat.no. C4

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius, c. 1642-1648

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

236

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius, 1617

copper, oil paint, 15.5 x 12 cm

center right: AET.44 /1617

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. OS-2003-18

cat.no. A4.1.1A

237

Detail of: Pieter de Grebber

Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius and his family, 1625

Amsterdam Museum (on loan from the Stedelijk Museum Alkmaar)

238

Detail of fig. 236

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius, 1617

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

239

Detail of fig. 235, reversed

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius, c. 1642-1648

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

240

Detail of fig. 234, reversed

Detail of cat.no. C3

Jacob Matham

Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius, 1618

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

241

Detail of fig. 236

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius, 1617

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

242

Detail of fig. 234, reversed

Detail of cat.no. C3

Jacob Matham

Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius, 1618

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

243

Detail of fig. 235, reversed

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius, c. 1642-1648

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

Notes

1 ‘MICHAEL MIDDELHOVEn/ Vndecima instillans populo trieteride Christum,/ Et septem-gemina prole beate Pater,/ Quum totam sacras natorum Pleiada Musis,/ Non aere, at docili vivere prole potes.’

2 The whereabouts of male portrait, which was confiscated in 1940 during the German occupation of Paris, remains unknown. Yet, judging from the surviving photographs its quality is similar to that of its pendant.

3 Morelli 1890-1893, vol. 1, p. 97-99

4 Ampzing 1621, p. D3; Ampzing 1628, p. 166-188.

5 ‘Komt Halsen, komt dan voord,/ Beslaet hier mee een plaetz, die u met recht behoord./ Hoe wacker schilderd Franz de luyden naer het leven!/ Wat suy’vre beeldekens weet Dirk ons niet te geven!/ Gebroeders in de konst, gebroeders in het bloed,/ Van eener konsten-min en moeder opgevoed’. Ampzing 1628, p. 371. See also: Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, doc. 41.

6 ‘En dan moet Heyndrick Pot sijn kroon ook billijk dragen./ ‘Tis wonder wat hy doet in dese onse dagen/ Met sijn suy’vre hand’. Ampzing 1628, p. 371.

7 ‘AmpsingI nescit publica fama mori./ Vivit in Ausonij percusso Praesulis oro’. And ‘Draconem. pia turba. tuum quid quaeris in aere.-/ Testentur melius laesa tot ora virum’. See the catalogue entry on C22 for the full inscription and translation.

8 ‘O Haerlem! Ziet hier AMPSINGS wezen,/ Die syne STAD ons geeft to lezen;/ Een HARDER, trou voor Godes Kerk,/ En vaerdig in des Heeren werk;/ Wiens heyl’ge RYMEN en GEDICHTEN/ In wak’ren ernst de vromen frichten:/ Met recht van yder Haarlems kind,/ En van des Heeren volk bemind’.

9 Pieter de Grebber, Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius and his family, 1625, oil on canvas, 130.0 x 171.6 cm, Alkmaar, Stedelijk Museum Alkmaar, inv. no 20982, on loan to the Amsterdam Museum.

10 Valentiner 1923, p. 306.

11 Bijl 2005, p. 53-54.