1.5 An understanding of craftmanship

Being able to closely observe every detail of a work of art has changed the mental presence of the entire history of painting. While the concept of a painter’s style had previously been determined by a selection of black-and-white photographs and greatly scaled down reproductions in books, we can now dispose of an unlimited amount of large-scale color reproductions available to any number of interested viewers – on any screen in the world. A wealth of new impressions has opened up to us, which can be reconfigured through cross-comparison with the other pieces of the puzzle that are spread all over the world.

35

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a man, c. 1643

Greifswald, Pommersches Landesmuseum, inv./cat.nr. A 228/17 411

© Pommersches Landesmuseum

cat.no. A1.108

36

Frans Hals (I) and workshop

Portrait of a woman, 1643

canvas, oil paint, 78 x 65 cm

lower left: AETATIS/46/SVAE/1643/FH

Greifswald, Pommersches Landesmuseum

© Pommersches Landesmuseum

cat.no. A3.43

One example where such a reassessment is overdue, concerns the Portrait of a woman of 1643 [36]. It has been repeatedly doubted in the literature and is listed accordingly in Slive’s 1974 catalogue under the ‘doubtful and wrongly attributed paintings’.1 Together with the Portrait of a man [35], the painting was donated to the municipal museum in Stettin (today Szczecin, Poland) in 1863. By then, the portraits were regarded as companion pieces, and the monogram on the male portrait had not yet been discovered. However, cleaning of the female pendant around 1937 raised doubts about the two portraits belonging together. And indeed, they did not originally form a pair. The female portrait had been matched to the size of the male portrait by enlarging the canvas. Also, the sitters can be disconnected because of their different postures. The man was captured whilst standing, observed by the artist from a lower point of view, probably seated. In contrast, the woman must have been seated opposite the painter at eye-level. The sideways turn of her body does suggest the presence of a male counterpart which has not been identified up to now. Unlike the male portrait associated with it, the female representation is not in good condition. The painted surface is abraded and was flattened through reworking. The contours of the cheeks and the chin are blurred, as are the hairline and the contour of the bonnet, which was strengthened later by another hand [37]. Nevertheless, accents typical for Hals are still present in the modelling of the eyes, nose, and mouth. The shyly amused gaze and a hint of a smile enliven the face. In contrast, from the ruff down the handling is stiff and smooth throughout. The longstanding rejection of this painting was most likely based on the deficiencies of this area. Judging from what we can perceive today, the hands, cuffs, and glove have been strongly reworked [38]. Even still, Hals’s brushwork is not clearly indicated anywhere in the shapes showing through from underneath.

37

Detail of fig. 36

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a woman, 1643

Greifswald, Pommersches Landesmuseum

© Pommersches Landesmuseum

38

Detail of fig. 36

Frans Hals (I) and workshop

Portrait of a woman, 1643

Greifswald, Pommersches Landesmuseum

© Pommersches Landesmuseum

Here and in many other cases we are faced with the phenomenon of the collaborative creation of paintings, not just in portraits and not just in paintings, but in every type of artistic creation. Through the awareness of artist’s training processes, workshop customs, and the practical execution of commissions, we know that the painters of the past were craftsmen with workshops and a collaborative production as a matter of course, which especially includes those most highly regarded today. Collaboration began with the preparation of supports and pigments, and continued with the application of ground layers and various paint layers up to the application of the signature and the final varnish.2 Critical and close-up observation now also confirm differences in the creative execution. Consequently, even works that are unequivocally attributed to Frans Hals contain mechanical and clumsy elements next to areas that are executed confidently and brilliantly. The idea of an uncompromisingly ‘artistic’ (in the modern sense) production of old master paintings is no longer tenable, neither here nor elsewhere. It stems from the modern concept of artistic genius and stands in the way of a pragmatic assessment of factual circumstances.

For such a pragmatic approach, we need to take guidance from the responsibilities of the time’s master painters, which were the composition of artworks and their execution. Both needed to be of a quality that matched the patrons’ or buyers’ expectations. But wielding the brush with one’s own hand was not necessarily part of the arrangement. In her dissertation The fingerprint of an old master, Anna Tummers (* 1974) quotes from the assessment of Giulio Romano’s (c. 1492/1499-1546) works in Giorgio Vasari’s (1511-1574) Lives of 1550 and concludes that ‘a work could count as being by a master if it was done under his supervision and after his design, and it was common for masters to collaborate with their assistants not only on large-scale commissions but also on modestly sized paintings. [...] It was also common in the Netherlands of the early 17th century for masters to attach their names to paintings that were in part or largely executed by their pupils and assistants’.3 Consequently, in our search for authentic evidence of an artist's personality we need to on the one hand go beyond the traditional selection of attributions, and on the other we need to take into account a varying proportion of contributions by the master and workshop assistants. The artworks by Hals that were signed at their time of origin, the artworks that are known through historical documents, and the artworks that can be identified via engravings, and drawn or painted copies, as well as the creations that have been attributed to him on a stylistic basis, are not merely testimonies of the towering ability of the master, but rather for the most part they are probably workshop achievements with a varying degree of contributions by Hals himself. Stylistic ambiguity and a relative inconsistency in the body of work we encounter in the monographs of this and many other painters, also supports such an approach. Similar to the assessment of the oeuvre of Rembrandt (c. 1606/1607-1669), there is no general consensus about the oeuvre of Frans Hals today – not even for the works owned by major museums and collections. Yet the starting point for profound analysis today has changed. Hals’s imagery and his idiosyncratic brushwork can now be observed on any computer screen in ever more examples of incomparable clarity. The resulting refined understanding of his individual characteristics allows a restructuring of visual impressions. It becomes apparent that Hals’s personal brushstrokes appear in varying forms across different groups of works, be it for an entire painting or limited to certain areas and motifs in a composition. What we observe in Hals’s paintings is no exception from the standard practice that applied to the time’s most successful artists – a group to which Hals did not belong. Especially court painters, who were of high social ranking, worked with assistants who enabled them to produce large-scale history paintings and portraits in numerous repetitions. Accordingly, we need to accept that in old master painting – that is European picture production up to the late 18th century – many famous masterpieces were not made by a single hand.

We can put this statement to the test with a portrait which I excluded from my earlier catalogues because the awkward execution of the hand could by no means be by Hals, who was a fiercely precise anatomist of hands. However, Hals’s authorship is supported by the no doubt original signature and date, as well as by the inscription F. Hals pinxit on a copper engraving of the same composition, which also identifies the sitter [40]. It concerns the portrait of the Lutheran preacher Conradus Viëtor (1588-1657) painted in 1644 [39], and engraved after Viëtor’s death by Jonas Suyderhoef (1614-1686). A representation of a theologian with a book, usually a bible, was a traditional model adopted in many other portraits of clergymen. But in contrast to the powerful grip used by, for example, Johannes Hoornbeeck (1617-1666) (A1.116) [41] to hold his book, the hands in the present portrait are lacking in expression and appear anatomically incorrect, crammed into the composition at the picture’s lower edge [42]. Comparison with the same area in the print by Suyderhoef conforms that the hands as they are visible in the painting today, looked like this back in 1657 and have not been restored or overpainted since [43].

39

Frans Hals (I) and workshop

Portrait of Conradus Vietor, 1644

canvas, oil paint, 82.6 x 66 cm

upper right: FH.M. CONRADVS VIETOR/AETATIS 56/A⁰ 1644

New York, The Leiden Collection, inv.no. FH-101

cat.no. A3.48

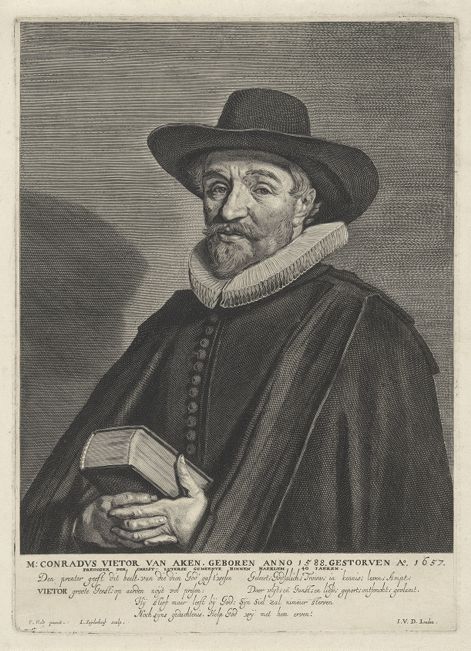

40

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of Conradus Viëtor, after 1657

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-60.773

cat.no. C40

41

Detail of cat.no. A1.116

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Johannes Hoornbeeck, 1645

Brussels, Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten van België

Photo: J. Geleyns

42

Detail of fig. 39

workshop of Frans Hals

Portrait of Conradus Vietor, 1644

New York, The Leiden Collection

43

Detail of fig. 40

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of Conradus Viëtor, after 1657

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

The hands and the two-dimensional treatment of the ruff and the dress, as I could see them in illustrations at the time, caused me to reject the attribution to Hals entirely. However, when I saw the cleaned painting in person in 2008, my impression changed. Today, the high-resolution image from The Leiden Collection allows one to admire the expressive facial area which is executed throughout in thin, but precisely placed brushstrokes in rising and falling diagonal directions – particularly on the edge of the cheek and the area of the nose [44]. Hals’s calligraphic brushwork is preserved from the eyebrows to the beard, clearly and without additions. The facial features appear as if captured in thoughtfulness, especially the area of the left eye with the raised brow above – revealing a tired gaze – but also the slightly open mouth, increasing the impression of labored concentration. Yet from the brim of the hat upwards and from the edge of the ruff down, a hesitant style of painting emerges. It is surprising that the master Hals did not object to these flatly rendered areas. Our contemporary approach would be to try to identify a consistently applied artistic concept, because we take the modern idea of the ‘Artwork’ as our starting point. Yet, if we accept the historical practice of collaboration, this very example illustrates the wide range of stylistic differences in one artwork that were tolerated at the time. Just how much the master himself executed on his own and what he delegated, was certainly based as much on efficiency as on the agreed remuneration. That the division of labor we see here was standard practice, is notable in various portraits of the time. Many of the most outstanding achievements by other great artists can be assessed in the same way, once regarded through a historically trained lens. For example, the 1640 portrait of the cabinet- and frame maker Herman Doomer (c. 1594/1596-1650) forms part of the small group of well-preserved autograph works by Rembrandt [45].4 Nevertheless, whether the painterly execution of the area below the ruff can be attributed to the master remains questionable [46] [47].5

44

Detail of fig. 39

Frans Hals (I) and workshop

Portrait of Conradus Vietor, 1644

New York, The Leiden Collection

45

Rembrandt and workshop

Portrait of Lambert Doomer, 1640

panel, oil paint, 75 x 55.3 cm

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv.no. 29.100.1

46

Detail of fig. 45

Rembrandt

Portrait of Lambert Doomer, 1640

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

47

Detail of fig. 45

workshop of Rembrandt

Portrait of Lambert Doomer, 1640

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Notes

1 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 154-155, no. D74.

2 Signatures were workshop markers and were certainly not only applied by the master himself. In Hals’s oeuvre, the spelling of the monogram varies and includes the variants FHF, FHFH and f.hals. f. – in addition to the generally always ligated FH in capitals.

3 Tummers 2009, p. 90.

4 Rembrandt, Portrait of Herman Doomer, 1640, oil on panel, 75.0 x 55.3 cm, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv.no. 29.100.1.

5 The same considerations apply to the execution of the pendant: Rembrandt, Portrait of Baertje Martens, 1640, oil on panel, 75.1 x 55.9 cm, St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum, inv.no. ГЭ-729.