2.8 What did Frans Hals look like?

Unlike Rembrandt (1606-1669), Hals only studied his own likeness as an exception. When he inserted his self-portrait into the 1639 Officers and Sergeants of the St George civic guard (A2.12), it was primarily to have a visible role among a group of prominent members of society. His discreet appearance in the background was not an artist’s portrait, but rather a recognizable likeness among the dignitaries of his former militia, not more [156]. The facial features captured in front of a mirror were transferred in a smooth style of painting into the designated position. Hals did not have to do this himself. The modelling of the shadow zones, especially in the nose and eye areas, is soft and careful – the schematic brushstrokes are particularly visible on the eyelids, above and below them. Hals’s typical brushstroke can, however, be identified on the moustache and goatee, on the nostrils, as well as on the hard shadow marks under the eyebrows and lower lids. In the hair, the wavy curl above the forehead and the two bright lines to the right of it are noticeable. Unfortunately, the perception of the painting today is impeded by the unusually pronounced craquelure of the paint layers.

Around ten years after the insertion of his self-portrait, by circa 1648-1650, the sole individual portrait of Hals was made, bust-size, wearing a hat. Considering the repetitions which are still preserved today, it was rather humble in size and the sitters was represented in a distanced attitude. The portrait appears like a swiftly sketched commemorative rendering rather than an ambitious self-representation. What its occasion was, and why so many repetitions were made of this reticent portrait, is hard to imagine. Liedtke assumed ‘the desire of collectors to own images of famous artists evidently led to the production of more “self-portraits” than the sitter cared to paint himself’.1 Coutré went even further when she wrote that the period from 1645 to 1650 ‘would have been an outstanding moment for him [Hals] to promote his achievements through the concept of the “self-portrait”’.2 Yet, we must not base our assumptions on today’s esteem of Hals and on modern marketing methods, but take into account the values and behavior of picture buyers in the 17th century. Neither was Hals perceived as a towering figure of the history of painting in his lifetime, nor was the collection of artist’s self-portraits a widespread practice in Holland at the time. There is also no information about a comparable group of self-portraits by Hals’s fellow painters in Haarlem (several of whom were much more successful and more highly regarded than Hals).

It was only in the mid-18th century that an artistic interest in the work and the portrait of Frans Hals began to develop. This first wave of discovery of the artist Hals is connected with the foundation of the Haarlem drawing academy in 1772 and their directors Cornelis van Noorde (1731-1795) and Wybrand Hendriks (1744-1831). We owe them many copies of 17th-century paintings, either drawn or painted in watercolors, especially from the Haarlem School and in particular of those by Frans Hals. Cornelis van Noorde was born in Haarlem and joined its guild of St Luke’s in 1761, where Frans Hals had already been a member. His special regard for Frans Hals is expressed in the ink drawing Allegory with the Portrait of Frans Hals, which he created at age 23 [157]. It depicts a rendering of the lost self-portrait, or indeed one of its copies, marked with the inscription ‘ipse pinxit’. Surrounding the portrait medallion, Hals’s life dates are noted as 1584-1666, and instead of Antwerp, Haarlem is given as his birthplace. Many years later, Van Noorde created a mezzotint rendering the present portrait type, inscribed ipse Pinxit, CV Noorde fe 1767 [158].

156

Detail of cat.no. A2.12

Frans Hals (I) and workshop

Officers and sergeants of the St George civic guard, 1639

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

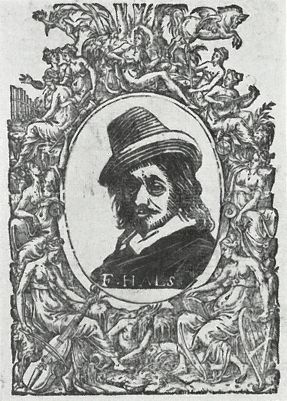

157

Cornelis van Noorde

Allegory with the Portrait of Frans Hals, dated 1754

Haarlem, Noord-Hollands Archief, inv./cat.nr. NL-HlmNHA_1100_49260

cat.no. D65

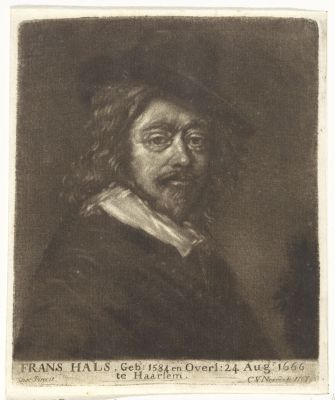

158

Cornelis van Noorde

Portrait of Frans Hals with a Hat, dated 1767

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1883-A-6918

cat.no. C57

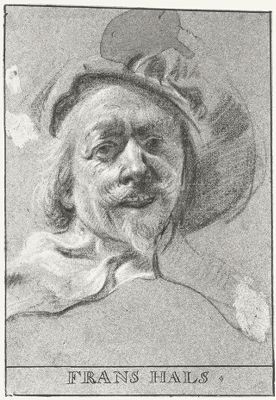

159

Anonymous

Portrait of Frans Hals

woodcut

whereabouts unknown

cat.no. C42a

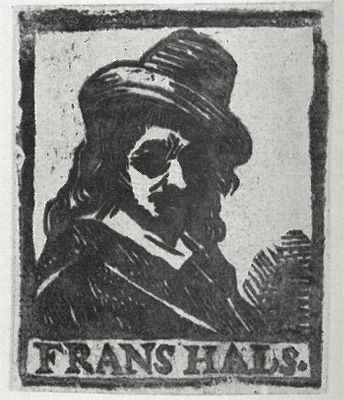

160

Anonymous

Portrait of Frans Hals

woodcut

whereabouts unknown

cat.no. C41

It is not known who created the two woodcuts in an antiquated style which are inscribed F. HALS and FRANS HALS, that also reproduce the Hals portrait [159][160]. Slive referred to presumptions that they were made by Cornelis van den Berg (1699-1774), Isaac Vincentsz. van der Vinne (1665-1740), Salomon de Bray (1597-1664) or Dirk de Bray (c. 1635-1694).3 Unfortunately, the self-portrait of Hals is not preserved in an autograph version. It is also not a given that Hals’s own painting was executed on a firm support; it could just as well have been just an oil- study on paper. Slive lists eight versions of the painting in total, with seven of them in an upright format and one a roundel.4 The version formerly in Denver is the only one with an FH monogram [161]. For a long time, the version in Indianapolis was considered the best, if not a possible original [162]. It is inscribed on the lower right 147, and this number corresponds to the 1722 inventory of the Dresden gallery which later sold the picture. In addition, there is a closely related copy similar in size which was also formerly in the Dresden gallery and now in private German ownership [163]. In the inventory of 1722, the latter was listed as an authentic self-portrait by Frans Hals. Nevertheless, the detailed comparison which is possible today does not allow any of the known versions to be regarded as original, or even of superior quality than the others. Slight variations between the versions can be found in the painterly technique, but also in the rendering of the hair, individual facial features, and collar. As far as an assessment based on a superficial comparison goes, they were created by different hands [164] [165][166]. Today’s detailed visual analysis gives rise to doubt whether the variants in Indianapolis and New York [167] date from the 17th century. The painterly technique of the version now in private German hands corresponds most closely to paintings from the circle of Frans Hals. However, the left eye has moved outwards slightly and lost its highlight.

The estate inventory drawn up on 4 January 1680 for the Amsterdam marine painter, dye works owner, and probably also art dealer Jan van de Capelle (1626-1679) lists as no. 32 ‘a portrait of the deceased by Frans Hals’, as no. 76 ‘a woman’s tronie by Frans Hals, being his wife’, as no. 99 ‘a rommel pot player by Frans Hals’, as no. 132 ‘the portrait of Frans Hals’, which may refer to a self-portrait by the master.5 Whether one of these listings referred to the original version of the abovementioned paintings or to one of the variants, cannot be determined. But further clarification could be reached via a dendrochronological analysis and age determination of the panels, precise analysis of the painterly technique and used pigments, as well as an inspection for underdrawings or traces of copying. In this way it may be possible to learn when these works were created and where. Only then can we decide if this is a series of workshop deliveries or later creations, and for what reason these copies may have been made. For now, our imagination of Frans Hals’s facial features can only rely on a combination of impressions combining the self-portrait of 1639 with the variant in German private holdings [163] and the fairly lively drawing by an unidentified author, which was first noted out by Norbert Middelkoop [168].6

161

after Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Frans Hals (1582/83-1666), after c. 1648-1650

Denver (Colorado), Denver Art Museum

cat.no. B17g

162

after Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Frans Hals (1582/83-1666), after c.1648-1650

Indianapolis (Indiana), Indianapolis Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 2015.28

cat.no. B17a

163

after Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Frans Hals (1582/83-1666), after c. 1648-1650

Private collection

cat.no. B17b

164

Detail of fig. 162

Portrait of Frans Hals, after c. 1648-1650

Indianapolis Museum of Art

165

Detail of fig. 167

Portrait of Frans Hals, after c. 1648-1650

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

166

Detail of fig. 163

Portrait of Frans Hals, after c. 1648-1650

Germany, private collection

167

after Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Frans Hals (1582/83-1666), after c. 1648-1650

New York City, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 32.100.8

cat.no. B17c

168

Anonymous Netherlands (hist. region) c. 1630-1640

Portrait of Frans Hals, c. 1630-1640

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-T-1961-51

cat.no. D1

Notes

1 Liedtke 2007, vol. 1, p. 302.

2 Coutré 2017, paragraph 15.

3 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 123.

4 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, no. L15.

5 ‘32. Een dito Conterfeijtsel van Frans Hals / 76. Een vrouwetrony van Frans Hals, sijnde sijn vrouw’ / 99. Een Rommelpot van Frans Hals / 132. Het Counterfeytsel van Frans Hals’. Gemeente Amsterdam Stadsarchief, 5075 Inventaris van het Archief van de Notarissen ter Standplaats Amsterdam, 95 – Adriaen Lock, inv.no. 2262B, p. 1187, 1188, 1190, 1192.

6 Middelkoop/Van Grevenstein 1988, p. 93.