3.4 The development of Frans Hals the artist

When we speak of ‘artistic development’ today, we understand this term to mean a progress towards a novel kind of aesthetic experience. In Hals's time, however, the focus was different and centered on what we would consider a symbolic experience. It was directed towards the reflection of the transcendental, be it in a higher being, message, or quality that was discernable behind the visible surface. Even 17th-century profane painting was a glorified interpretation of phenomena in this world; including people, whose higher importance could be conveyed in portraits. This symbolic experience depended on the interpretation of the world and the scope of learning, and it shifted with the consciousness of perception and its limits. As such, it became continuously more indirect and more reduced. Within the limits of his professional focus on the representation of human appearance, Hals responded in ever more radical ways to the fading of symbolic visibility – to the point of a disintegration of representation into individual color slashes. Yet within this development there were four distinct stages.

The first and most important stage took place around 1616, when Hals moved away from a Mannerist style, demonstrating the influence of Flemish painting, and in particular of scenes and portraits painted by Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640). The second stage was based on the model of the painters of the Utrecht school who had been influenced by the art of Caravaggio (1571-1610), leading to a lighter and more colorful palette around 1623/1624. A third stage is discernible in the middle of the 1630s, characterized by the use of effects of reflected light and shadows assuming vivid color, possibly under the influence of Rembrandt (1606-1669). Around 1640, the fourth stage is marked by a shift to a more greyish palette and an overall flatter and more painterly free execution.

Hals began to work within the traditional confines of a strict symbolism of portraiture. In the 15th century, individual features and hands had entered the field of intense observation and painted representation. This naturalist approach, however, was not compatible with the symbolic qualities that were used to depict the supernatural in medieval painting: gold ground and halos, pure colors and linear geometric symbolism. Only the superior naturalism of painting and sculpture from classical antiquity offered a formal expression for higher consciousness. Their shapes seemed to outline the underlying basic laws of beauty and spirituality that would apply to any depiction of the human body and face. Therefore, even modern portraits adopted an idealized shape based on antique statues and busts that lifted the portrait into a sphere of historical projection. This type of artificially enhanced character shaped the symbolism of the Mannerists, though it is more obvious in sculptures and engravings than in paintings. The sculptural, highly defined, rigid style that had dominated Netherlandish portraiture from Jan van Scorel (1495-1562) and Maarten van Heemskerck (1498-1574) to Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617), formed the point of departure for Frans Hals's portrait painting.

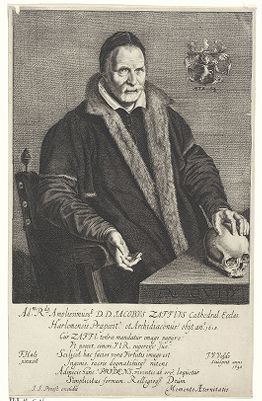

There is still a sense of the marble chill of traditional portraiture in Hals's earliest preserved work, a bust of the priest and Haarlem archdeacon Jacobus Zaffius (1534-1618) [39]. At the beginning of the 17th century, the spiritual ambition in depicting a human being becomes evident in the wide-angle perspective and the composition loaded with references, as can be seen in the engraving of the lost larger version of the Zaffius portrait [40]. The priest's gestures unite life and death, as his right hand expresses eloquence [41] and his left is resting on a skull [42]. This is confirmed by the inscription: ‘Memento Aeternitatis’. Zaffius's features emerge from darkness, illuminated by exaggerated lighting. His fixed gaze is almost demonic. Other early portraits by Hals, including that of Pieter Cornelisz van der Morsch (A1.3), echo the extreme spotlighting and rhetorical staging of the Zaffius portrait.

39

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Jacobus Hendricksz. Zaffius, 1611

panel, oil paint, 54.5 x 41.2 cm

upper left: AETATIS SVAE/77 AN⁰ 1611

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. OS I-511

cat.no. A1.1

40

Jan van de Velde (II)

Portrait of Jacobus Hendricksz. Zaffius (1534-1618), dated 1630

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-15.269

cat.no. C1

41

Detail of fig. 40, reversed

Portrait of Jacobus Hendricksz. Zaffius, 1611

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

42

Detail of fig. 40, reversed

Portrait of Jacobus Hendricksz. Zaffius, 1611

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

However, by 1616 at the latest, Hals moved away from his use of an extreme wide-angle view towards a narrower field of vision with the focus on the brightly-lit head of the portrayed person. While previous pictures had been composed of different elements, the picture plane can now easily be taken in at one glance. The scene is lit solely by sunlight falling at an angle from above into the room, such as in the two pendants, now at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts [43] and Chatsworth House (A1.5). Even though the man is portrayed with his right hand in a rhetorical gesture and holding a skull, the viewer is presented with a relaxed and naturally familiar sitter. Here, the pictorial reality has changed. Instead of a heroic person with momentous gestures, we now see an amiable, naturally plausible sitter with the attribute of a skull that refers back to the universe of meaning from a previous period in portraiture painting. A change of paradigm had taken place, which anchored the image in the here and now, the everyday and the arbitrary. Such a merely momentary impression, aided by a still traditional way of lighting, implied a massive confinement in meaning, almost like a parody of the past. Instead, a new immediacy and credibility of representation was attained.

Inspired by the compositions of Rubens and his followers, Hals created paintings from 1616 onwards that were clearly momentary observations, capturing arrested movements of figures at close quarters. In the group portrait of the officers of the St George civic guard [44], that, as Slive aptly put it, ‘announced the Golden Age of 17th century Dutch painting like a gun salute’,1 Hals employed a new and natural emphasis. Also, the figures are positioned in a narrow spatial setting and arrayed in a lozenge-shaped tableau, both side by side and above each other. The result is a fanned-out juxtaposition of individual impressions. This loose sequence of single portraits, comparable to a string of pearls, enabled Hals to create an unusual variety of individual types through expressive postures. The facial features revealed by the slanting light generate a diversity of entirely different visual shapes. The ever-changing pattern of light-dark contrasts and sections of bright color contributes to a varying appearance of the heads and faces, further differentiated by the range of emotions displayed in the facial expressions. Combined with the figures’ postures and body movements, this creates a varied interplay. Instead of a ‘Memento Aeternitatis’, the individuals' vitality is emphasized through the close-up depiction and exaggerated coloring, while their energetic movement is conveyed through momentary stills of facial and physical motion, which correspond to the rising and falling rhythm in the composition. The impression of movement is on the one hand generated by the positioning of the figures and their gestures, and, for the first time, also by the fluent application of impasto color streaks, creating a rhythmical glow of corresponding color sections in the flags and costumes.

Hals's breakthrough as a portrait painter was built on the success of this first group portrait of Haarlem civic guard officers. He had achieved to depict a previously unknown presence in the complacent movements of the portrayed personalities. Subsequently, Hals also began to emphasize movement in his single portraits. Despite he reduced some of the dignity of the traditional portrait, and emphasized on the randomness of certain aspects, and despite of the general sketchiness of his depictions, Hals’s clients – who were well aware of the symbolic importance of their portraits – accepted his new approach. Also an exaggerated use of glowing colors came into play. The over-intense shades of yellow and red in the cheeks, and the invigorating reflections from the white collars evoke the luminous flesh tones of Rubens and Jacob Jordaens (1593-1678), especially in the features of women and children [45] (A1.5, A1.12). It seems likely that Hals only came into intense contact with these Flemish masters during his trip to Antwerp, that began sometime before 6 August 1616. He returned to Haarlem between 11 and 15 November of the same year.

From 1623, Hals’s restrained arm movements close to the body and the dark-colored palette that are still evident in the 1622 Portrait of Isaac Abrahamsz. Massa (A1.13) and the Portrait of a family, possibly Ghijsbert Claesz. van Campen, Maria Joris and their children [46], were replaced by a new influence, that of the Utrecht Caravaggists and possibly of other painters that had been under Caravaggio's impact. The sudden adoption of half-figure compositions depicting drinkers, musicians and actors, with their expressive body movements and gestures, transformed the picture production in Hals's workshop. This radical change is documented in the Lute player [47] which was painted in 1624 at the latest. Its proximity to pictures by Hendrick ter Brugghen (1588-1629), Gerard van Honthorst (1592-1656) and Dirck van Baburen (c. 1592/93-1624) dated 1622, 1623 and 1624 can only be explained by an encounter with an entire array of these or almost identical works – take, for example, Van Baburen’s Procuress of 1622, Honthorst's 1623 Merry Fiddler and The concert, his slightly later Merry violinist with a glass of wine, and finally, Ter Brugghen's Singing lute player of 1624 [48].251 Hals’s lute player is superior to these other versions of the same motif in one respect: a consistent observation of the moment. Highlights and cast shadows are emphasized and at the same time integrated into the visual rhythm of parallel diagonals, causing the focus to be not so much on the illumination of the figure and his position, but rather on the surprising impression of a fleeting instant. Instead of a frozen moment, as so often occurs in the Utrecht examples [49], Hals’s approach results in a visual impression of a brief pause.

The Utrecht influence becomes apparent so abruptly that a trip by Hals to Utrecht can be assumed. It remains unclear when and with whom among the Utrecht painters or picture dealers a direct contact was established. Leonard Slatkes furthermore underlined the Utrecht influence on the Haarlem painters in Pieter de Grebber’s (c. 1600-1652) Musical Trio [50] even though Hals’s Young man and woman in an inn of 1623 [51] already adopts a Caravaggist gesture as well.2 This being said, the reorientation of the Hals workshop seems to have been prompted by a sudden intensified contact. Half-length depictions of musicians in Caravaggesque style had already been created in Utrecht for some time, as demonstrated by Ter Brugghen’s 1621 Flute player, Abraham Bloemaert’s (1566-1651) Flute player of the same year, and Van Baburen’s 1622 Young man singing.3 Nevertheless: ‘It appears, that Honthorst did not isolate the merry musicians from his larger compositions until 1623’.4 It may have been precisely the latter’s light-colored and planar compositions which resonated with Hals’s approach and which came to his attention through either engravings by Theodor Matham (c. 1605/06-1676) or other artists or art dealers.

43

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a man holding a skull, c. 1616

Birmingham (Great Britain), The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, inv./cat.nr. 38.6

cat.no. A1.4

44

and Cornelis Hendriksz. Vroom (II) Frans Hals (I)

Banquet of the officers of the Saint George civic guard, dated 1616

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv./cat.nr. OS I-109

cat.no. A2.0

45

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a woman, c. 1619

Kassel, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel), inv./cat.nr. GK 214

cat.no. A1.11

46

and Salomon de Bray and Gerrit Claesz. Bleker Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Gijsbert Claesz. van Campen (c. 1584/1585-1645), Maria Joris (c. 1585-1666) and their children, c. 1623-1625

Toledo (Ohio), Toledo Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 2011.80

cat.no. A2.3

47

Frans Hals (I)

Lute player, c. 1624

Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv./cat.nr. R.F. 1984-32

© 2018 RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Mathieu Rabeau

cat.no. A1.15

48

Hendrick ter Brugghen

Singing lute player, dated 1624

London (England), National Gallery (London), inv./cat.nr. 6347

49

Detail of: Gerard van Honthorst

The concert, 1623

Washington, National Gallery of Art

50

Pieter de Grebber

Musical trio, c. 1620-1623

Bilbao (Spain), Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao, inv./cat.nr. 69/114

Photo: © Google

51

Frans Hals (I) and workshop

Young man and woman in an inn, 1623

canvas, oil paint, 105.4 x 79.4 cm

upper right: FHALS 1623

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv.no. 14.40.602

cat.no. A3.3

Hals did not only take up motifs and compositional schemes from the Utrecht Caravaggists, he also continued reworking them to make them his own. Unlike the examples, his pictures do not capture moments frozen in time. Through a heightened awareness of perception, they render a ‘real’ impression of movement, generated through applying paint in strokes, conveying the semblance of capturing something in a hasty scribble. It seems likely that the field of experimentation for these spontaneous observations lay in the genre pictures painted for the open market. Hals’s depictions of children, exuberant young people and representatives of everyday life such as fish and fruit sellers, singers and musicians, actors, prostitutes and drinkers remained unusually sketchy, demonstrating a painterly tendency that needed to be tempered in commissioned portraits – though this is less noticeable in the group pictures of Haarlem and Amsterdam civic guards than in single portraits.

The most astonishing ensembles of figures with different degrees of movement are presented by the group portraits of the officers of the St George civic guard (A1.30) and the St Hadrian civic guard [52], probably painted in 1626 and 1627. Different types and degrees of facial and body movement are juxtaposed, unfolding an entire repertory of varying twists, as well as arm and hand movements. These probably serve both as a means of characterization of the individuals and as a way of enlivening the composition. However, Hals's snapshots do not simply illustrate a general liveliness, they are observations of individual emotion, centered in the animated eye movements and continuing in the slight tension of the facial expressions, the arms and the hands. Over the following period, similar elements can be found in a number of single portraits and, even more pronounced, in the genre paintings.

Hals often presented his single portrait sitters in a dominant pose, and increasingly seen from below. They seem to appear as on a plinth or a stage ramp. There, they swagger in the luxury of their expensive clothes, like the Laughing cavalier of 1624 (A1.16) with their arms akimbo, or turning their raised chests towards the viewer. These overly dramatic appearances – blatantly obvious in the portraits of Heythuysen (A2.6) and Roosterman [53] – signal distinguished self-presentation in line with conventional portraiture. But at the same time, Hals emphasized a spontaneous behavior in the sitters' gaze that was directed by the interaction while sitting for the painter, and independent of the assumed pose [54]. In this way he was able to display a range of emotional expressions, from looking coolly suspicious to bored, from amused interest to the eye's affable wink and the features indicating the beginning of a conversation, all within the framework of the sitter's more or less spontaneous turning either towards or away from the viewer.

The theatrical distance of costumed performers on the portrait stage subverted conventions; it was a hitherto unfamiliar observation of reality. While Hals was painting, he or an entertaining companion must have drawn the sitters out of their formal reserve time and again, provoking either amicable attention or manifestations of distance and willfulness. Comparisons with portraits by Hals's contemporaries demonstrate just how unusual it was for sitters to forget their composure. ‘Van Dyck's aristocratic world remained outside of Hals' ken. Hals' genius was to endow the less formal, more personal side of man's nature with a new authority’, as Slive remarked with regard to the distinction between Hals's sharply observed faces seen in close-up and Anthony Van Dyck’s (1599-1641) idealized models whose positions are by no means spontaneous [55].

52

and Pieter de Molijn Frans Hals (I)

Banquet of the officers of the Calivermen civic guard, c. 1627

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv./cat.nr. OS I-111

cat.no. A2.8A

53

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Tieleman Roosterman (1597-1672), dated 1634

Cleveland (Ohio), The Cleveland Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 1999.173

cat.no. A1.65

54

Detail of fig. 52, Ensigns Adriaen Matham and Lot Schout in lively interaction with colonel Willem Claesz. Vooght

Frans Hals (I)

Banquet of the officers of the Calivermen civic guard, 1627

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

55

Anthony van Dyck

Double Portrait of Lord John Stewart (1621-1644) en Lord Bernard Stewart, later Earl of Lichfield (1623-1645), c. 1638

London (England), National Gallery (London), inv./cat.nr. NG 6518

The next stage of Hals’s development concerned the re-evaluation of the angular modelling of faces and figures using hues of colour. The three-dimensional, sharply modelled features of heads, hands and bodies were replaced by softly applied sections of opaque colour, which no longer distinctly set off from the background colour. Hals adopted the effects of warm-toned lighting and bright reflections as used by Rembrandt and his school, in order to achieve softly modelled transitions and to animate his faces with colour. Examples of this subtly brightened palette range from the faces in the Meagre company (A2.11)[56], the 1634 Portrait of Tieleman Roosterman [57], to the 1639 group-portrait of the St George civic guard’s officers and sergeants (A2.12). Overall, the impression of the paintings became more painterly and planar.

56

Detail of cat.no. A2.11, Lieutenant Cornelis Michielsz. Blaeuw

Frans Hals (I)

Militia company of district XI, 1633-1637

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

57

Detail of fig. 53

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Tieleman Roosterman, 1634

Cleveland, The Cleveland Museum of Art

58

Detail of cat.no. A1.82

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Nicolaes Pietersz. Duyst van Voorhout, c. 1636-1637

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

59

Detail of cat.no. A1.102, François Wouters

Frans Hals (I)

Regents of St Elisabeth’s Hospital, c. 1640-1641

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

If Dudok van Heel’s fascinating hypotheses prove to be correct, Hals and Rembrandt must have met several times in the home and workshop of Hendrick Uylenburgh (1587-1661), and Hals must have had the opportunity to study works by his younger colleague.5 However, the encounter left few distinct traces in the painting style of either. One may well wonder whether the phase in Hals’s development between 1634 and 1637 – characterized by a smooth and fine modelling, and a cultivation of the transitions between light and dark – may be attributable to Rembrandt’s influence. While in Hals’s earlier portraits, the parts of the face that lay in the shadow had simply been darker and less colorful, starting with the Portrait of Nicolaes Hasselaer (A1.62) and the face of ensign Nicolaas van Bambeeck in the Meagre company, he started to employ more subtle transitions of modelling in those areas, as well as more tonal reflections. The best example illustrating the reduction in sharply-lit contours by employing light coming from above at an angle, and by cultivating intense tones in the shade and half-shade areas, is the Portrait of Nicolaes Duyst van Voorhout from c. 1636/1637 (A1.82) [58]. Moving on to the group-portrait Regents of St Elisabeth’s Hospital (A1.102), painted in 1641, where the soft lighting and warm dusky tonality have suddenly disappeared [59]. A previously unknown sharpness has entered with the grey and grey-black passages that shape the sitters’ features at the temples, noses and chins. The three-dimensional appearance of their bodies, but also the emphasis on the volume of the heads and hands have receded into an overall twilight atmosphere. In contrast, the individual facial features and finger movements are highlighted even more.

The change in Hals’s visual approach can be described in terms of concentration on salient features and reduction of visual means of representation. The most important facial features are now emphasized; at the same time, areas outside the actual zone of the face are treated as two-dimensional and colorless. The palette is newly arranged in accordance with the psychology of perception. Few tones: brick red, yellow ochre, matte brown, black, and white are mostly sufficient to carve out faces and figures. From this time on, Hals’s portraits are to a lesser extent representations of his sitters and rather – within the framework of conventional portraiture – become even more marked impressions of their facial expressions, their posture and movements. This description can be applied to the repertoire of expression that Hals was to adopt henceforth until his final paintings from the mid-1660s. The earlier capturing of bodies and decorative details of clothing was replaced by dark silhouettes whose contours form a grid of rising and falling lines together with the light and shaded edges of the fabrics. This abstract pattern corresponds with the contours of the faces, collars, and cuffs, forming a visual framework for them.

Hals’s experimentation can be appreciated in the juxtaposition of two paintings: Portrait of a man, c. 1640 [60] and Portrait of a man, c. 1643 [61]. Both are half-length portraits of unidentified sitters, lit from the side, featuring similar clothing, and both have their right hand placed on the chest in an affirmative gesture. Both were painted with a similar palette and their compositions are largely comparable. Yet, one can also observe that the earlier portrait was approached in an overall more figurative manner. The head is modelled consistently, collar and folds of the coat are rendered equally coherently. The contours run along similar lines, but we are still faced with entirely different temperaments of the sitters. This impression is based above all on the already quite liberated brushwork in the later portrait in Greifswald [62]. The diagonal movement of the many repeated parallel stripes creates an impression of something fleetingly perceived and equally captured with quick slashes of the brush. An independent dynamic seems to pervade the whole figure. What still appears here as a regular pattern was varied on by Hals in the 1650s in an increasingly loose form of paint application. However, after 1645 there are only a few pictures that are entirely autograph by him. They can only be dated indirectly, on the basis of their circumstances of creation, information about the sitter or stylistic observations. The latter can be interpreted in two directions, primarily in the emphasis on visual effects and the focus of the representation on momentary impressions. A typical example for the mixture of keen observation and intentional lack of definition is the Portrait of a man in Zurich (A1.129) [63], which in spite of an independent brushstroke displays a friendly, approachable expression. An even more liberated technical approach was adopted by Hals only in the Portrait of a man with a slouch hat, c. 1663-1664 (A1.130), as well as in some areas of the contemporary Regents of the Old Men's Almshouse (A3.62).

60

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a man, c. 1640

Private collection

cat.no. A1.101

61

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a man, c. 1643

Greifswald, Pommersches Landesmuseum, inv./cat.nr. A 228/17 411

© Pommersches Landesmuseum

cat.no. A1.108

62

Detail of fig. 61

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a man, c. 1643

Greifswald, Pommersches Landesmuseum

63

Detail of cat.no. A1.129

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a man, c. 1662-1664

Zürich, Bührle Foundation

A second stylistic development can be discerned at the level of the very free brushwork and can only be understood as an age-related loss of the dexterous ability to draw and model with a brush. The facial proportions are clearly captured, the sense of colour is precise, as is the gradation of light and shade. But the drawn highlights, contours and shade lines are unsteady. They are short, staccato stripes which do not appear in any earlier paintings. Their form and insecure application can be explained by the short range of the hand when painting using a painting stick, as is illustrated in a print by Vincent Laurensz. van der Vinne II (1686-1742) [64].6 Signs of this only still tentative handling are discernible in the small, well-preserved portrait in the Mauritshuis (A1.131) [65], where they are still part of the brilliant overall effect. This is not the case with the approximately contemporary portrait which reappeared at auction a few years ago [66] (A1.132). Doubts expressed in the literature with regard to an attribution to Frans Hals are only too understandable. The badly preserved painting, which was further mistreated in restorations, was described by Valentiner as a portrait of a man ravaged by syphilis, which prompted Slive to comment: ‘It seems that the painting, not the sitter, suffered from a disfiguring malady’.7 This comment is correct insofar as the noticeable shortcomings in execution may relate to Hals’s infirmity caused by his old age. The thin lines with which the nostrils, lip and corner of the mouth are rendered only further support what can already be seen in the Mauritshuis portrait and the faces of the Regentesses of the Old Men’s Almshouse (A3.63). But even still, traces of the diagonal shadow contours are visible and with them, Hals’s typical composition. This picture is a fragment, but at the same time it is a moving final document of Hals’s portraiture.

In this last phase of Hals’s career, the majority of the paintings were made in collaboration with workshop assistants, one painter in particular, most likely to be his son Frans. The most important late works, the group portraits of the regents and regentesses of the Old Men’s Almshouse in Haarlem (A3.62, A3.63), therefore do not display a consistent execution. The main part of the regents’ portrait is attributable to Frans Hals himself, while the larger part of the depiction of the regentesses shows the assistant’s handwriting [67]. The differences between the two are recognizable in stylistic and technical terms. While the assistant worked in a flat manner with opaque, surface-covering paint, Hals’s own contributions are only thinly drawn, the facial details rendered in short narrow brushstrokes and delicate lines.

More than almost any other master of European painting, Frans Hals demonstrates a continuous process of reflection. The carved-out modelling of what is visually significant – from the sitter’s bearing and gestures to their body movement and facial expression – gradually dissolves towards a basic impression of the facial features that, while only fleetingly observed, still manages to convey a lasting impact with just a few accents. This reduction into a ‘web’ of brushstrokes follows its own, quite comprehensible logic. It consistently leaves behind the traditional classical concepts of importance and the ‘Artistic’, while the focus remained convincingly on the fleeting momentary impression of emotional impulses as a valid and truthful conclusion.

64

Vincent Laurensz. van der Vinne (II)

Painter in his workshop, 1714-1758

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-62.383

65

Detail of cat.no. A1.131

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a man, c. 1664

The Hague, Mauritshuis

66

Detail of cat.no. A1.132

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a man, c. 1664

sale New York (Sotheby’s), 2 February 2018, lot 34

67

Detail of cat.no. A3.63

Frans Hals (I)

Regentesses of the Old Men’s Almshouse, c. 1663-1664

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

Notes

1 Haarlem 1962, p. 3.

2 Dirck van Baburen, The procuress, 1622, oil on canvas, 100.2 x 105.3 cm, Boston, Museum of Fine Arts; Gerard van Honthorst, The merry fiddler, 1623, oil on canvas, 108 x 89 cm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum; Gerard van Honthorst, The concert, 1623, oil on canvas, 123 x 206 cm, Washington, National Gallery of Art; Gerard van Honthorst, Merry violinist with a glass of wine, c. 1624, oil on canvas, 83 x 68 cm, Madrid, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza.

3 Slatkes 1981-1982, p. 173-174.

4 Hendrick ter Brugghen, Flute player, 1621, oil on canvas, 71.3 x 55.8 cm, Kassel, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister; Abraham Bloemaert, The flute player, 1621, oil on canvas, 69 x 57.9 cm, Utrecht, Centraal Museum; Dirck van Baburen, Young man singing, 1622, oil on canvas, 71 x 58.8 cm, Frankfurt am Main, Städel Museum.

5 Judson/Ekkart 1999, p. 190.

6 Dudok van Heel 2006, p. 116, 332.

7 This early 18th-century view of a painter’s workshop demonstrates the working conditions of a painter of large formats – probably quite similar to Hals’s situation.

8 Valentiner 1941, p. 296, note 6; Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 150.