3.5 Hals’s recognition by his contemporaries

Literary figures

The strength of expression and the vibrancy of Hals’s paintings were certainly felt by individual viewers even when they were first created, and described as such in contemporary documents. For example, in 1647 Theodorus Schrevelius (1572-1649) wrote in his history of Haarlem that Frans Hals

‘[...] excels almost everyone with the superb and uncommon manner of painting, which is uniquely his. His paintings are imbued with such force and vitality that he seems to defy nature herself with his brush. This is seen in all his portraits, so numerous as to pass belief, which are coloured in such a way that they seem to live and breathe’.1

Cornelis de Bie (1627-1711), author of artist biographies, wrote about Hals in a similar vein in 1661, when he referred to him as the teacher of the landscape and horse painter Philips Wouwerman (1619-1668), who was much more famous for a long time:

‘He [Wouwerman] studied with Frans Hals, who is still alive and living in Haarlem, a marvel at painting portraits or counterfeits which appear very rough and bold, nimbly touched and well composed, pleasing and ingenious, and when seen from a distance seem to lack nothing but life itself’.2

These two quotes, which come up again and again, seem to prove that during his time Frans Hals was already regarded in almost the same way as he is seen by us. The secondary literature typically mentions further references to his painting, but they are always the same, and all too few. References from the 17th century by Frans Hals’s contemporaries are spread across the following documents:

- Samuel Ampzing, Het lof der stadt Haerlem in Hollandt, Haarlem 1621. The ‘Halsen’ Frans and Dirck are referenced in three lines as part of a list of sixteen painters.3

- Samuel Ampzing, Beschryvinge ende lof der stadt Haerlem in Hollandt, Haarlem 1628. Gives one line each to Frans and Dirck: ‘how dashingly Frans paints the people from life!/ How neat the little figures Dirck gives us’. And expressing praise for the group-portrait of the Calivermen (A2.8A) in another phrase: ‘a large-scale piece of painting […] done most boldly from life’.4

- Aernout van Buchel, hand-written travel, notes dated 10 January 1628. Refers to a visit to Schrevelius in Leiden. He was shown his host’s portrait by Hals, which he described as ‘painted most vividly’.5 Van Buchel also mentions receiving an engraving by Jan van de Velde II (1593-1641) after Hals’s portrait of Petrus Scriverius (1576-1660) (A4.1.4, C9).

- Theodorus Schrevelius, Harlemias, Haarlem 1647 (Latin ed.), 1648 (Dutch ed.).

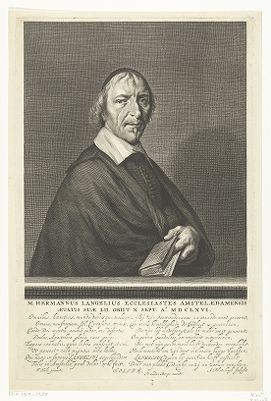

- Herman Frederik Waterloos, epigram to Hals’s portrait of Herman Langelius (1614-1666) (A4.3.51). States that ‘Haarlem may be proud’ of the artist’s ‘early masterworks’, but that now his ‘eyesight is too blurred for the brilliance of scholarship and your deformed hand too coarse […]’.6

- Cornelis de Bie, Het gulden cabinet vande edel vry schilder const, Antwerp 1661. Includes the abovementioned remark on Hals in the short biography of Philips Wouwerman.

- Balthasar de Monconys, Journal des voyages de Monsieur de Monconys, Lyon 1665-1666. With a remark about Hals’s civic guard paintings that he had seen in August 1663.7

- Matthias Scheits, on the frontispiece of his copy of Karel van Mander’s Schilder-Boeck, 28 May 1679. The German painter Scheits, a pupil of Wouwerman, who in turn had trained with Hals, wrote about the ‘most excellent portrait painter’, who ‘was somewhat lusty in his youth’, and who, ‘when he was old and no longer able to earn a livelihood from his painting (which was not as fine as formerly), [...] the noble government of Haarlem paid him money for his upkeep for some years until his death, because of the merits of his art’.8

- Arnold Moonen, Poëzy, Amsterdam 1700. Features a poem, dated 1680, that we can list as another echo from the same period. It was composed as a reaction to Hals’s portrait of the preacher Jan Ruyll, sadly either lost or as yet unidentified: ‘There is the portrait of your devout Ruyll, Oh Haarlem, your hero, your support, and pillar of temple peace, as naturally as if he lived, Thanks to Hals, whose brush ingeniously glides In and out. But if the spirit of the man had ever charmed you, Retain the lessons heard from his golden mouth. 1680’.9

This is a surprisingly meagre compilation. Apart from the succinct wording by Ampzing – who went on to comment in equal length and similar well-chosen words on the de Grebbers, Judith Leyster (1609-1660) and a number of other painters – and the curt remarks by the other authors, Schrevelius’s and de Bie’s considerations were the only detailed observations of Hals’s representational achievements that were printed during the artist’s lifetime. This is precious little for 55 years of activity by a master painter. Such a minimal acknowledgement of Hals’s life’s work cannot be compared to the response generated by other 17th century artists such as Rubens, Poussin, Van Dyck, Rembrandt, and many others.

Examined in detail, the words of praise do not offer an insight into the Haarlem painter’s outstanding talent. Even the most effusive statement of 1647, that Frans Hals surpassed ‘almost everyone in his wonderful and unusual way of painting’, must be seen in context. Its author, the humanist and Latin school rector Schrevelius, gave his own most significant portrait commission not to Hals, but to the successful history and portrait painter Pieter de Grebber (c. 1595/1605-1652/1653), who took on the group-portrait of Schrevelius surrounded by his family in 1625 [68].10 The man himself had been portrayed by Hals in 1617 in preparation for his portrait engraving of 1618 [69]. Comparing the words of praise on Hals with those Schrevelius expressed for De Grebber, their content is qualified even further: ‘Pieter de Grebber is so inventive as he is excellent in his painting, that he deserves to be counted among the best painters of our century’.11 This is more and clearer than the antique formula adopted with regard to Hals, that the painter ‘seemed to challenge nature itself with the force of his paintbrush’.

The appreciation of Hals in the framework of its historical place and time cannot be expressed better than by Jessica Veith: ‘The books of town praise by Ampzing and Schrevelius emphasized local artists as a major source of Haarlem’s fame, highlighting the city’s long lineage of great artists both past and present’.12 It was certainly an honour for Hals to be mentioned there and receive commissions himself from the leading authors Ampzing, Schrevelius, and Scriverius. The portrait commission from Schrevelius was especially prominent since it generated two engravings, one of them elegant and richly decorated by Jacob Matham (1571-1631) with a eulogy by Petrus Scriverius of 1618 and the later one by Jonas Suyderhoef (1614-1686) from the time between 1642 and 1648 (C4).

From the perspective of being flooded with media in the industrial age, early engravings may appear incidental, especially since it is a cumbersome craftsmen’s technique of modest accuracy in representation, yet the historical appreciation of the engraver’s art is an entirely different matter. Michiel Roscam Abbing recently referred to a previously disregarded letter written by Schrevelius to his learned friend Scriverius, with a request for eulogistic verses from the latter for his own portrait engraved by Jacob Matham. In the Latin text, he calls the ‘sculptor Maethanius’ ‘effigiem meam vivis coloribus expressam aeri insculpsit, et simul memoriae consecravit’, that is, he ‘engraved my portrait expressed in colours close to life into a copper plate and thus made it immortal for commemoration’.13 The remark about the ‘colours close to life’ must be read as praise for Hals, whose name is not mentioned, however. Nevertheless, these lines express that the rank given to the copper engraver who ‘made it immortal for commemoration’, was nearly as high as that of the painter. The achievement of the engraver appears as that of a sculptor in the line ‘engraved into ore’. Even if the panegyrical tone of the letter exaggerates, it describes the making of a portrait engraving as an independent artistic undertaking. In the same vein, Jan van de Velde’s (1593-1641) engraving of Jacob Matham after a design by Pieter Soutman (c.1593/1601-1657), refers to the former as ‘sculptor’ and ‘artifex’.14 This concept matches the inscription beneath the portrait of Schrevelius, engraved by Matham:

‘Because he bridled so many hard mouths of wayward youths,

With the force of his eloquence and his Palladian discipline,

Schrevelius was worthy, Mathanius, of your copper […]’.15

The equally great art and the further-reaching medium was in fact the engraving, whose execution was more strenuous and time-consuming than creating the painted or drawn model portrait. In general, the work of the engravers had reached a pinnacle of perfection since the 16th century. This was especially true for the ability to render artworks of all kinds, both with regard to the precise capturing of the motif and to the nuances of expression. The Haarlem engravers were among the most brilliant in Europe.

68

Pieter de Grebber

Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius and his family, dated 1625

Amsterdam, Amsterdam Museum, inv./cat.nr. 131

69

Jacob Matham

Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius (1572-1653), dated 1618

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-27.290X

cat.no. C3

Patrons and collectors

In comparison, the appreciation of Hals’s painting by his contemporaries can only be gauged indirectly, through the actions of patrons and buyers of paintings on the free market. Consequently, it is fair to say that Hals’s pictures were appreciated by them within the limits of their requirements. As documented in inventories and other sources, individual works by Hals could be found in Amsterdam, Leiden, The Hague, Rotterdam and Delft, but not in well-known collections, and only occasionally in one of the great houses. The only exception is the collection of the wealthy owner of crimson dyehouses and landscape painter Jan van de Cappelle (1626-1679), that comprised a total of 192 paintings and 7.000 drawings. He commissioned his portrait from Hals – as he did from Rembrandt and Gerbrand van den Eeckhout (1621-1674) – and his holding of nine works by Hals formed ‘the largest recorded 17th-century collection of his works. [...] Rembrandt, Rubens and Van Dyck were not as well represented; Van de Cappelle possessed six, four and six paintings respectively attributed to them’.16 But Van de Cappelle was a painter himself, even though he was an autodidact without membership in the guild. It seems likely that this is precisely why he was so unusual in his own painting and so unconventional in purchasing works by contemporary colleagues. Unfortunately, none of the portraits for which he sat has survived.17

This fellow painter was a special case. As far as details are known, any ambitious commissions to Hals outside of Haarlem can be traced back to the sitters’ business contacts and relatives in this town. This certainly seems to be the case for Paulus Verschuur (1606-1667) from Rotterdam [70], whose sister lived in Haarlem. It also goes for the above-mentioned Schrijver-Soop family in Amsterdam (A1.83, A1.95), close relatives of the Haarlem philologist and poet Petrus Scriverius – who had Latinised his original family name Schrijver. Hals had painted him and his wife in 1626 (A4.1.4, A4.1.5). It is also true with regard to the Amsterdam brewer Nicolaes Hasselaer (1593-1635), who had a Haarlem background (A1.62),18 and the Utrecht theologian Johannes Hoornbeeck (1617-1666), who was born in Haarlem [71]. Taking these cases as general examples, it must be said that they do not substantiate a far-reaching reputation for the artist Frans Hals, but rather indicate an awareness of Hals’s achievements and probable recommendations among the Haarlem upper class. The surviving documents confirm the practice of portrait painting as a challenging achievement of craftsmanship, which recorded members of important families and societal institutions as well as particularly worthy individuals. Portrait commissions were mostly given locally, where the posing of sitters could be arranged fairly easily. In this context it is understandable that Hals had his main clientele among the wealthy families in Haarlem, similar to Rembrandt’s Amsterdam portrait patrons as demonstrated so convincingly by Gary Schwartz.19 Hals delivered a wealth of individual portraits for his upper middle class patrons, as well as several large format group pictures and family portraits.

At the same time, commissions at a comparable level of remuneration were equally given to Hals’s fellow painters in Haarlem, especially for group portraits. Compared in retrospect, it has been noted that Hals’s fellow painters in Haarlem, Frans Pietersz de Grebber (1573-1649), Pieter Claesz Soutman (c. 1596/1601-1657), Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck (1601/1603-1662), and later Jan de Braij (c. 1626/1627-1697) also received commissions for group paintings in the same price range. The modern admiration for Hals can only imagine that these artists were influenced by Hals, whom they must therefore have regarded as a superior artist. ‘Hals remained supreme, or at least supremely popular. Until the end of his life, he continued to receive commissions from the wealthiest and most prestigious families in Haarlem’.20 This assessment is put into perspective, however, if we take into consideration that the majority of Hals’s commissions – even when these were few in number – and also the grant for the impoverished elderly painter from the Haarlem city council, came from the same group of the local upper middle class. Its members acquired Hals’s paintings as appropriate representations of individuals and commemorative objects, but deliberately not as ‘art’. This perception would only begin to change in the 18th century, through Cornelis van Noorde (1731-1795) and the Haarlem drawing academy.

A pre-modern concept of ‘art’ tied to historical purposes of representation is better suited to today’s understanding of the considerations which led the distinguished cloth merchant Ghijsbert Claesz. van Campen († 1645) to turn to Salomon de Bray (1597-1664) in 1628, instead of Frans Hals, for the addition of a child’s portrait to the large-scale family portrait by Hals, from c. 1623-1624 [72][73]. De Bray took on this task and his signature and the date of 1628 mark his quite skilful and cleverly executed insertion of the seated child. Such treatment of a commissioned and elaborate work, however, demonstrates the picture's prime purpose. Not the ‘art’ of a specific painter was the main concern, but rather an impressive representation of an important family, that was to serve long-term as its commemoration. Such an achievement required considerable but ultimately practical skill, and patrons would request portraits in turn from Hals, De Bray and other members of the guild of St Luke.

Consequently, Hals did not exclusively receive all portrait-commissions in Haarlem; there are at least two documented examples, particularly from his later period, where portraits were instead contracted to his competitors, probably quite deliberately. For instance, the group portraits of the regents and regentesses of St. Elisabeth’s Hospital, dated 1641, were granted to Hals [74] and Verspronck [75].21 And also the commission that followed directly afterwards went to Verspronck: The Regentesses of the Holy Spirit Almshouse in Haarlem.22 The choice for Verspronck was hardly circumstantial. We do not know which contemporary paintings by Hals drove the Haarlem regentesses as well as all other decision-makers in their choice for an artist, but if we consider today’s known paintings from around 1640, the differences with Verspronck’s approach are clear. Certainly, the patrons were familiar with the 1641 group painting of the regents, which is entirely autograph – unlike Hals’s guardsmen portrait of 1639 (A2.12). Even though it used to be much brighter than today, Hals’s muscular, austere representation and his cool palette could have prompted the move to Verspronck. Had the ladies seen a portrait like the one today in Gent [76], their decision becomes even more understandable. Verspronck’s painting displays a fully worked-out three-dimensional shape of the heads [77]. The lines around the eyes and mouth convey an impersonal, obliging expression, and the faces are covered with a smoothly rendered skin in a consistently light shade. All four women are depicted in this idealizing style, which – though fundamentally different from Hals’s manner – has its own charm and artistic merit.

70

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Paulus Verschuur (1606-1667), dated 1643

New York City, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 26.101.11

cat.no. A1.107

71

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Johannes Hoornbeeck (1617-1666), dated 1645

Brussels, Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten van België, inv./cat.nr. 2245

Photo: J. Geleyns

cat.no. A1.116

72

and Salomon de Bray and Gerrit Claesz. Bleker Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Gijsbert Claesz. van Campen (c. 1584/1585-1645), Maria Joris (c. 1585-1666) and their children, c. 1623-1625

Toledo (Ohio), Toledo Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 2011.80

cat.no. A2.3

73

Detail of fig. 72, The youngest daughter of the Van Campen family, 1628

Salomon de Bray

Portrait of Ghijsbert Claesz. van Campen, Maria Joris and their children, c. 1623-1624

Toledo Museum of Art

74

Frans Hals (I)

Regents of St Elisabeth’s Hospital, c. 1640-1641

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv./cat.nr. OS I-114

cat.no. A1.102

75

Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck

Regentesses of St Elisabeth's Hospital in Haarlem, dated 1641

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv./cat.nr. OS I-622

76

Detail of cat.no. A3.36

Frans Hals (I) and workshop

Portrait of a woman, 1640

Ghent, Museum voor Schone Kunsten

77

Detail of fig. 75, Beatrix Herculesdr. Schatter

Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck

Regentesses of St Elisabeth’s hospital, 1641

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

There are noticeably few female sitters in Hals’s late and mature works. A portrait of Cornelis Guldewagen (1599-1663) [78] painted by Hals’s workshop around 1660, was combined with a pendant of his wife Agatha van der Horn (1603-1680) by Jan de Braij in 1663 [79]. Therefore, it was not just the desire for equal distribution among different members of the Haarlem painters’ guild, but possibly also a conscious aversion by some patrons to the angular characterisation in Hals’s portraits. They seem to have preferred a smooth ‘fijnschilder’ picture, in keeping with academic ideals and above all, flattering to the sitter. The late Portrait of an unknown woman now in Oxford [80] largely corresponds in size and composition to the Portrait of Agatha van der Horn. Just as the latter, it was conceived as a companion piece to a no longer extant counterpart. The painting technique is fairly close to that in the Guldewagen portrait, as such giving an impression of the later female portraits that were produced in the Hals workshop. The patron Cornelis Guldewagen was the owner of the brewery Vergulde Hart in Haarlem and served as mayor several times. His brother-in-law Andries van der Horn (1600-1677) had been painted twice by Hals, once in the group-portrait of the officers and sergeants of the Calivermen civic guard of 1632/1633 (A2.10), and in 1638 in an individual portrait (A1.93) that was paired with a counterpart depicting his wife Maria Olycan (1607-1655) (A1.94). Through these relations Guldewagen was connected to the Olycan family, whose members appear in a total of 17 group and individual portraits. Pieter Biesboer described this clientele, which was so important for Hals, in detail.23

The greatest recognition that Hals received over the course of his working life were the repeated commissions for group paintings, for which he kept inventing compositions that were as innovative as they were convincing. Every single one of these big commissions was a challenge, not least because all sitters to be represented were important figures in society. Hals mastered these assignments with the greatest success and gained access to the sitters, which won him further commissions for individual portraits either for themselves or from their circle. An especially prestigious assignment was the group painting of 16 full-length portraits of officers and other guardsmen of the XIth district of Amsterdam’s crossbowmen’s civic guard that Hals received in 1633 (A2.11) From today's perspective Hals seems the obvious choice – in view of his relevant achievements in Haarlem, especially the Meeting of the Officers and Sergeants of the Calivermen civic guard of 1632/1633 (A2.10), which features several standing guardsmen. At the time, however, the choice for Hals was unusual, as there were several well-known local painters who could have handled an ambitious undertaking of this kind. With the exception of a commission to Paulus Moreelse (1571-1638) from Utrecht in 1616, so far only local painters had been employed for civic guard group paintings in Amsterdam.24

The later commission for the group portraits of the regents and regentesses of the Old Men’s Almshouse once again presented a particular challenge for the Hals’s powers of representation (A3.62, A3.63). Especially as it may be assumed that the elderly painter’s brittle brushstroke was not easily conveyed to the sitters, his appointment for these paintings can be considered an homage to his life's work. However – and this has not been considered to date – the regents and regentesses of the Old Men’s Almshouse were not in a position to be very selective. This becomes clear when taking stock of the painters of group portraits that had been active in Haarlem up to that date, and which of these were still available in the early 1660s. Pieter Soutman had died in 1657; Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck followed in 1663. Jacob van Loo (1614-1670), who had painted the regents and regentesses of the Haarlem Alms-, Poor- and Work House in 1658 and 1659 respectively,25 had left for Paris in 1660, and Jan de Braij was busy at the time with the two group portraits of the regents and regentesses of the Haarlem Children’s Almshouse, as well as the painting Caring for the children at the orphanage, that were completed by him in 1663 and 1664.26 In this respect, it was divine justice, and perhaps the schedule of the patrons, that gave Hals another opportunity in his old age. Finally, the commission may also have been influenced by differences in the fee that was charged by the artists.

78

workshop of Frans Hals (I), possibly Frans Hals (II)

Portrait of Cornelis Guldewagen, c. 1660-1663

panel, oil paint, 40.6 x 30.4 cm

Champaign, Krannert Art Museum, inv.no.1953-1-1

cat.no. A4.3.54

79

Jan de Braij

Portrait of Agatha van der Horn (1603-1680), 1663

Luxembourg, Villa Vauban - Musée d’Art de la Ville de Luxembourg, inv./cat.nr. 51

80

workshop of Frans Hals (I), possibly Frans Hals (II)

Portrait of an unknown woman, c. 1658-1660

panel, oil paint, 44.5 x 34.3 cm

Oxford, Christ Church Picture Gallery, inv.no. PO589

© Christ Church, University of Oxford

cat.no. A4.3.50

Reworkings

Hals’s focus on the facial expressions and the precision of his brushwork vividly conveyed his sitters’ temperament in a way which is admired by the modern viewer. But this distinctiveness could have been perceived differently by those who sat for him. In fact, Hals’s brushwork was reworked and smoothed over in a number of portraits, especially female ones, most likely because they did not meet the sitters’ expectations. In one case, the Portrait of Maritge Claesdr. Vooght (A3.33), a contemporary copy attributed to Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck indicates that the reworking was carried out rather soon after the completion by Frans Hals [81]. Similarities in painting technique also suggest that the portraits of the sister and the brother-in-law of the sitter, Cornelia Claesdr. Vooght (c. 1578/78- after 1631) (A3.20) and Nicolaes van der Meer (c. 1574-1637) (A3.19) were reworked in the same period. Future restorations will have to prove to what extent the original paint can be revealed again, by removing the overpainted areas. In many instances this will not be possible anymore, yet a reduction of the falsification will make the original representation more imaginable. The three cases presented below are visible in high resolution images.

The face in the Portrait of Maria Pietersdr. Olycan of c. 1638 (A1.94) appears fully original, with an undisturbed paint layer [82]. The same can be said of the much later Portrait of an unknown woman (A4.3.50), in which very thin brushstrokes are visible [83]. When compared to the 1638 Cleveland Portrait of a woman (A1.88), later cosmetic reworkings become apparent. Large shares of the face have been overpainted in a softer manner. The eyebrows, eyelids, the skin under the eyes, as well as the contours of the woman’s lips, chin and cheeks have been smoothed out and repainted more delicately [84]. The contemporaneous Portrait of a woman, now in Frankfurt (A1.92), displays a different kind of reworking [85]. Here, the lit areas of the forehead and cheeks have been strengthened with white paint, whilst the eyebrows and shaded temple on the right side have been smoothed out. In the rest of the painting, Hals’s characteristic are still preserved and visible. The next painting in this comparison, the Portrait of Maritge Claesdr. Vooght, dated 1639 (A3.33), displays later interventions as well. Hals’s own handwriting can be discerned in the lips and lower edge of the nose, yet the highlight on the nose has been painted over. This also goes for the cheeks, nostrils, shadow of the nose, eyelids, eyebrows: a covering layer of paint has been applied throughout [86]. The undated Portrait of a woman in London (A1.98), finally, features a sitter with a sceptical gaze and compressed lips that are the result of Hals’s own observation. Unfortunately, the areas around the eyes, the mouth, the chin and the left cheek have been overpainted and the paint layer is damaged overall [87].

81

attributed to Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck

Portrait of Maritge Claesdr. Vooght, 1639 or later

panel, oil paint, 68.5 x 57.8 cm

sale New York (Sotheby’s) 6 June 2012, lot 36

cat.no. A3.33a

82

Detail of cat.no. A1.94

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Maria Pietersdr. Olycan, 1638

São Paulo, Museu de Art de São Paulo

83

Detail of fig. 80

workshop of Frans Hals (I), possibly Frans Hals (II)

Portrait of an unknown woman, c. 1658-1660

Oxford, Christ Church Picture Gallery

84

Detail of cat.no. A1.88

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a woman, 1638

Cleveland, The Cleveland Museum of Art

The surface is smoothed, the hard edges of the bruststrokes have been softened and the impasto paint layer shows a network of atypical craquelures

85

Detail of cat.no. A1.92

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a woman, 1638

Frankfurt am Main, Städel Musum

86

Detail of cat.no. A3.33

Frans Hals (I) and workshop, or later overpainter

Portrait of Maritge Claesdr. Vooght, 1639

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

The right half of the face has been overpainted in several areas: eyelids, cheek, right-hand nasolabial fold, eyebrows

87

Detail of cat.no. A1.98

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a woman, c. 1639

London, National Gallery

Example of a thinly painted and untouched surface

Critical perceptions

Portraits were more than just depictions of a model; they were understood as representations of the significance of their sitter. On the one hand, the artistic execution was expected to depict the person in a recognizable manner, and on the other hand, to convey the sitter’s aura of distinguished aspiration. Such an understanding, for example, can be deduced from the inscription under the 1618 engraving after Hals’s portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius (C3):

‘So that if perchance envious time should blot out his name

And hide the man, this likeness may speak for him’.27

The inscription below the 1630 engraving after the portrait of the priest Jacobus Hendricksz. Zaffius (1534-1618) (C1) defines ‘speaking’ more precisely:

‘Why is the likeness of Zaffius entrusted to fragile paper?

So that the Man may outlive his ashes.

In truth, this face is the image of true Virtue,

Shining with intelligence and holy doctrine’.28

Conversely, some criticism of pictures was aimed not at ‘aesthetic deficiencies’ but rather at an insufficient spirituality of the representation. For example, Herman Frederik Waterloos wrote in a poem about Hals’s portrait of the Amsterdam priest Herman Langelius (A4.3.51), published in 1660:

‘Why, old Hals, do you try and paint Langelius?

Your eyes are too dim for his learned lustre,

And your stiffened hand too crude and artless

To express the superhuman, peerless

mind of this man and teacher.

Haarlem may boast of your art and early masterpieces,

Our Amsterdam will now bear witness with me that you

Have perceived not half the essence of his light’.29

Langelius was a well-known figure in Amsterdam. This combative clergyman had received particular attention through his condemnation of Joost van den Vondel’s (1587-1679) play Lucifer. Upon Langelius’ objections, the textbooks were confiscated and the play was cancelled after only two performances in the municipal theatre of Amsterdam in 1654. Vondel was the most important Dutch poet of the 17th century and an advocate of confessional tolerance. He was also critical towards the Calvinists, who dominated Holland at the time. Langelius was one of their vociferous proponents. After his death in 1666, his portrait engraving [88] was printed and disseminated, with a Latin text surpassing any other praise of the dead:

‘To all, heretics, the world, waverers and sinners,

he was everything, shipwreck or sea, guiding-start or earthquake.

In his heart, a devotee of God; in his soul, a ray of light; in his voice

A Paul in his eloquence, a rare glory to the apostolic flock.

A bachelor, he was married to his books, and a man to whom

His life was a labour devoted to propagating children for Heave,

Such – O, how sad to say! – was his likeness here on earth in Amsterdam’.30

It is unknown how the commission for the print came about; it may have been a successive task after one of the numerous portraits of preachers by Hals whose engravings were already widespread. Accordingly, the painted portrait could also have been created with the intention of making an engraving after it [89]. In any case, the engraver smoothed over the areas of the face and hand, which had been structured by choppy brushstrokes, and made them more recognisable [90][91]. Faced with the painting preserved in Amiens today, only the composition outline and perhaps some of the facial features hidden under the upper paint layer today can be attributed to Frans Hals himself. Whether a separate facial study was created by him or whether he drew details himself onto the picture surface cannot be extrapolated from the current appearance of the painting. And it seems to have been accessible to viewers long before Langelius’s death in 1666: the non-reversed engraving by the Amsterdam copper engraver Abraham Bloteling (1640-1690) was also created at an early stage, since prints are preserved that were made before the insertion of the posthumous eulogy. In any case, the commission to Hals was the subject of a critical discussion, as expressed in the quoted poem by Herman Frederik Waterloos.

Portraits were a medium of visual remembrance which aimed primarily at the timeless importance and only secondarily at the unique features of the sitters. The idea that a ‘superhuman intelligence’ or other spiritual elements could be discerned from a human’s outer appearance, is pure illusion from a modern point of view. Nevertheless, in earlier periods this was conveyed through traditional means of emphasis: by bearing and gestures, formulaic elements of distinction in the ambience, lighting, typical clothing and of course also through the tradition of portrait painting and engraving itself, which were reserved for a socially elevated group. Nevertheless, Frans Hals directed his focus on his sitters’ individuality and spontaneity. He looked into their eyes at close distance and observed their private emotions. He permitted himself this intimate or even indiscreet perspective, but it was not a concern of the portrait commissions at the time. In this respect, Hals’s analytical precision of observation and his reflexion on the truth and reality of visual impressions related more to scientific study of nature and spontaneous observation than to the contemporary idea of ‘art’. The latter was based on the Classical ideal of creative design as expressed in the formula of antique rhetoric, where equal importance was given to ingenium (skill/talent), exercitatium (practice) and ars (studying the rules). The critical comments on Hals listed by Frances Jowell relate to this same rhetorical standard of achievement in ‘art’, that continued to influence critical judgements until the 19th century: ‘Thus by the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Hals’s bravura virtuosity, inseparable from his feckless character, was denigrated as a slapdash procedure which resulted in an unacceptable flaw in terms of contemporary taste – negligent lack of finish’.31

88

Abraham Bloteling

Portrait of Herman Langelius (1614-1666), after c. 1658

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1907-2987

cat.no. C55

89

workshop of Frans Hals (I), possibly Frans Hals (II)

Portrait of Herman Langelius, c. 1658-1660

canvas, oil paint, 76.6 x 63.8 cm

center right: FH

Amiens, Musée de Picardie

photographies Michel Bourguet

cat.no. A4.3.51

90

Detail of fig. 88

Abraham Bloteling

Portrait of Herman Langelius, after c. 1658

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

91

Detail of fig. 89

workshop of Frans Hals (I), possibly Frans Hals (II)

Portrait of Herman Langelius, c. 1658-1660

Amiens, Musée de Picardie

photographies Michel Bourguet

Notes

1 ‘[…] by nae alle overtreft, want daer is in sijn schildery sulcke forse ende leven, dat hy te met de natuyr selfs schijnt te braveren met sijn Penceel, dat spreecken alle sijne Conterfeytsels, die hy gemaeckt heeft, onghelooflijcke veel, die soo ghecoloreert zijn, dat se schijnen asem van haer te gheven, ende te leven’. Schrevelius 1648, p. 383. See: Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, doc. 116.

2 ‘Hy heeft gheleert by Franchois Hals oock noch in’t leven ende tot Haerlem woonachtich is die wonder uytsteckt in’t schilderen van Pourtretten oft Conterfeyten, staet seer rou en cloeck, vlijtigh ghetoetst en wel ghestelt, plaisant en gheestich om van veer aen te sien daer niet als het leven en schijnt in te ontbreken’. De Bie 1661, p. 281-282. See: Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, doc. 163.

3 Ampzing 1621, n.p. See: Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, doc. 28.

4 ‘Hoe wacker schilderd Franz de luyden naer het leven! Wat suy’vre beeldekens weet Dirk ons niet te geven. […] Daer is van Franz Hals een groot stuck schilderije van enige Bevelhebbers der schutterije in den Ouden Doelen of Kluveniers, seer stout naer ‘tleven gehandeld’. Ampzing 1628, p. 371. See: Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, doc. 41.

5 ‘[…] pictam admodum vivide […]’. Aantekeningen betreffende meest Nederlandse schilders en kunstwerken, Utrecht University Library, Hs. 1781 (Hs 5 J 21), fol.17v.

6 ‘Uw ooghen zyn te zwak voor zyn gheleerde straale; en uwe stramme handt te ruuw, en kunsteloos. […] Stoft Haarlem op uw kunst, en jonghe meesterstukken […].’ H.W. Waterloos in Van Domselaar 1660, p. 408.

7 ‘[…] il y a force grands portraits de ces Messieurs assemblez, & vn entre autres d’Als, qui est auec raison admire des plus grands peintres’. De Monconys 1665-1666, vol. 2, p. 159.

8 ‘Den treffelicken Conterfeiter […] hei is in sein Jeugt wat lustich van leven geweest, doen hey out wass ende mit sein schilderen (hetwelcke nu nit meer wass als weleer) nit meer de kost verdinen kon […] van de Ed. Overicheit van Haerlem, seker gelt tot sein onderhouding gehat, om de deigt seiner Konst’. Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, doc. 190.

9 ‘Dit is de beeltenis van uw’ getrouwen Ruil, O Haerlem, uwen helt, uw kerkpilaer, en zuil / Der tempelvrede, zoo natuurlyk of hy leefde. Men dank’ dit Hals, wiens kunstpenseel dus geestigh zweefde / Met hoogh en diep. Doch heeft ’s Mans geest u ooit bekoort, Bewaer de lessen, uit zyn’ gulden mont gehoort. / 1680’. Moonen 1700, p. 679-680. See also: Slive 1970-1974, vol. 1, p. 201.

10 This composition shows the difficulty of combining eight individual head studies and equally as many pairs of hands into one proportionally convincing arrangement. The face of the central figure is too small in relation to the large children’s heads.

11 ‘Pieter de Grebber is soo geluckigh in inventie als suyver in ‘t schilderen / dat hy by de beste Schilders onser eeuwe meriteert gestelt te worden’. Schrevelius 1648, p. 382.

12 Veith 2011, p. 17.

13 Haarlem 2013, p. 137.

14 Jan van de Velde, Portrait of Jacob Matham, 1630, engraving, 202 x 135 mm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum.

15 ‘Cum tot dura vagae fernaverit ora iuventae,/ Viribus eloquy, Palladijsque minis;/ Dignus erat Mathame tuo Schrevelius aere, […].’ See also: Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 141.

16 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 151.

17 Norbert Middelkoop pointed out to me that a portrait by Van Eeckhout in the Amsterdam museum had been identified as that of Van de Cappelle, but not with certainty.

18 Dudok van Heel 2015, p.139.

19 Schwartz 1985, p.132-166, 143-227.

20 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 39.

21 Even though both paintings feature the same three-quarter figures positioned around a table, the staging of the scene and the style of painting are entirely different. Bearing in mind the process of combining individual studies, Verspronck’s group-portrait demonstrates especially clearly the individual, stiff body positions, without any spontaneous (inter)action.

22 Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck, The regentesses of the Holy Spirit Almshouse in Haarlem, 1642, oil on canvas, 173.5 x 240.5 cm, Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum.

23 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 27-33.

24 P. Moreelse, Officers and other civic guardsmen of the IIIrd district III of Amsterdam, under the command of Captain Jacob Gerritsz. Hoyngh and Lieutenant Nanningh Florisz. Cloeck, 1616, oil on canvas, 169 x 333,5 cm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. SK-C-623. London/The Hague 2007-2008, p. 120.

25 J. van Loo, Portrait of the Regents of the Alms-, Poor- and Work House in Haarlem, 1658, oil on canvas, 159 x 237 cm, Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. os i-245; Portrait of the Regentesses of the Alms-, Poor- and Work House in Haarlem, 1659, oil on canvas, 158 x 221 cm, Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. os i-246.

26 J. de Braij, The regents of the Children’s Almshouse in Haarlem, 1663, oil on canvas, 186 x 250 cm, Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. os i-32; The Regentesses of the Children’s Almshouse in Haarlem, 1664, oil on canvas, 188 x 242 cm, Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. os i-33; Caring for the children at the Orphanage in Haarlem: Three Acts of Mercy, 1663, oil on canvas, 132,5 x 154 cm, Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. os i-31.

27 ‘Ut si fort’ aetas obliteret invida nomen, /Dissimulet qu’virum, posset imago loqui’. See also: Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 141.

28 ‘Cur ZAFFI. tenerae mandatur imago papÿro / Ut possit, cineri. VIR. superesse suo. / Scilicet hac facios verae Virtutis imago est / Ingenio. sacris dogmatibusqu’. nitens'. See also: Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 132.

29 ‘Wat pooght ghy ouden Hals, Langhelius te maalen? / Uw ooghen zyn te zwak voor zyn gheleerde straale; / En uwe stramme handt te ruuw, en kunsteloos, / Om ’t bovenmenschelyk, en onweêrgaadeloos / Verstant van deeze man, en Leraar, uit te drukken. / Stoft Haarlem op uw kunst, en jonghe meesterstukken, / Ons Amsterdam zal nu met my ghetuighen, dat / Ghy ’t weezen van dit licht, niet hallef hebt ghevat’. H.W. Waterloos in Van Domselaar 1660, p. 408. See also: Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 352.

30 ‘Omnibus, haereticis, mundo, dubiisque, malisque. / Omnia, naufragium, sal, Cynosura, tremor./ Corde Dei mystes, anima jubar, ore disertus / Paulus Apostolico Gloria rara gregi. / Expers connubii, quia libris nupserat, et cui, / Ut pareret caelo pignora vita labos./ Qui nunc in superis LANGELIUS angelus, idem / Talis in Amstelio, proh dolor! Orbe fuit. See also: Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 352, note 1.

31 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 63.