3.6 Colleagues and competitors

Hals's patrons were not concerned with their mere likeness, or with an ‘artistic’ impression of their person, but rather with an appearance which their contemporaries would see as glamorous and which future generations would find impressive. The likeness needed to be sufficiently accurate, but some very perceptive characterisations of their appearance could bring the sitter rather too close for comfort and could be interpreted as demeaning or embarrassing. Some vain patrons would conclude that next time, they should be shown in a more flattering light and employ another, though rarely cheaper, artist. For example, by 1654, Jasper Schade van Westrum (1623-1692) did not return to Hals – who had already painted his portrait in 1645 [92] – to order portraits of himself and his wife. Rather, he commissioned the fashionable painter Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen (1593-1661) for a pair of standing three quarter-length portraits [93].1 However, this shift was also related to the artist’s and sitter’s place of residence. Schade van Westrum came from Utrecht, where he resided all his life, while Jonson van Ceulen had moved to that city from Amsterdam in 1652. The comparison of the two portraits made nine years apart is especially instructive, as Schade van Westrum was a particularly lavish patron who took great pride in his appearance. Consequently, he had himself painted by Hals already at the age of 22, dressed in fashionable attire. His later portraitist Jonson van Ceulen better fitted his goal of prestige, since he was a successful artist employed by families from the English aristocracy and the London court, and as such he guaranteed an elegantly restrained type of representation.

92

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Jasper Schade (1623-1692), c. 1645

Prague, Národní Galerie v Praze, inv./cat.nr. O 638

cat.no. A1.115

93

Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen (I)

Portrait of Jasper Schade (1623-1692), dated 1654

Enschede, Rijksmuseum Twenthe, inv./cat.nr. 698a

Typically, patrons would look for a painter nearby, where the sittings could be done under reasonable circumstances. There were not that many fellow portraitists in Haarlem during Hals’s career, but there was a small number that reached a high level of quality:

- Frans Pietersz. de Grebber (c. 1573-1649), painter of portraits and history paintings, art dealer;

- Hendrick Pot (c. 1580-1657), painter of history paintings, allegories, genre scenes and small-scale portraits;

- Salomon de Bray (1597-1664), architectural designer and painter of history paintings and portraits;

- Pieter Soutman (c. 1593/1601-1657), draughtsman, engraver, publisher, painter of history paintings and portraits;

- Pieter de Grebber (c. 1600-1652/1653), painter of history paintings and portraits, architectural designer;

- Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck (1601/1603-1662), almost exclusively portrait painter.

94

Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck

Portrait of Johan de Wael (1594-1663), dated 1653

London (England), art dealer Agnew's

95

Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck

Portrait of Aeltje Dircksdr. Pater (1597-1678), 1653 (dated)

Berlin (city, Germany), Gemäldegalerie (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin), inv./cat.nr. 877 A

Photo: Dietmar Gunne

We owe excellent portraits of sitters outside Hals’s clientele to these painters, as well as of patrons who were painted by Hals before or after. The comparison of these depictions expands our perception of the sitters and sharpens our understanding of the respective artistic achievement. One of many examples is that of Johan de Wael (1594-1663), married in 1620, brewer, member of the city council, burgomaster, colonel and eventually captain of the St George civic guard. He had himself and his wife portrayed by Hals. The now lost pictures were last reported at auction in Amsterdam in 1851, described as ‘broad and masterfully treated’. 2 The same couple was painted by Verspronck in 1653 [94] [95], probably later than the portraits by Hals and in a slightly larger size.3 Long before, in 1624, De Wael had already been painted by Franz Pietersz. de Grebber as the captain – fourth from the left – in the group portrait of the St George civic guard [96]. Marieke de Winkel has attempted to identify the lost paintings by Hals with a male portrait in a private collection [97] and a female portrait in Cleveland [98], which would indeed fit, based on the approximate age of the sitters.4 Nevertheless, a comparison of facial features does not confirm this hypothesis. It does, however, provide insight into the generous and sharply observant treatment of facial features by Verspronck.

96

Frans Pietersz. de Grebber

Ten officers of the Sint-Jorisdoelen, dated 1624

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv./cat.nr. OSI-100

97

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a man, c. 1640

Private collection

cat.no. A1.101

98

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a woman, dated 1638

Cleveland (Ohio), The Cleveland Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 1948.137

cat.no. A1.88

Equally important documents for the history of portraiture are the several portraits of wholesale trader and banking partner Joseph Coymans (1591-after 1660), and his wife Dorothea Berck (1593-1684). These have been created in Haarlem as well as in Amsterdam, depending on the residence of the Coymans family and the locations of their businesses. For example, there are the anonymous pendants dated 1648, formerly in Huis Bingerden [99] [104].5 Second, there is the fine painting by Jacob van der Merck (c. 1610-1664), dated 1641, which recently appeared in the art trade [100]. In addition, there is the ambitious pair by Govert Flinck (1615-1660), of 1647 [101] [105]. Hals’s paintings of the Coymans couple of 1644 were created in between these dates [102] [103]. Slive noted that in 1644, the couple celebrated the wedding of their daughter Isabella Coymans (†1689) and Stephanus Geraerdts (†1671).6 It could well be that the paintings were intended for the new household of the young couple. However, no particular events can be tied to the dates of the other paintings, in which the costly outfits are noticeable, especially the hairdos.

99

Anonymous Northern Netherlands (hist. region) dated 1648

Portrait of Joseph Coymans, dated 1648

private collection jhr. mr. W.E. van Weede

100

Jacob van der Merck

Portrait of Joseph Coymans (1591-after 1660), dated 1641

Madrid (city, Spain), art dealer Soraya Cartategui

101

Govert Flinck

Portrait of Joseph Coymans, 1647

canvas, oil paint, 75.2 x 62.7 cm

sale Zürich (Koller), 16-21 September 2013, lot 3064

102

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Joseph Coymans (1591-?), dated 1644

Hartford (Connecticut), The Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 1958.176

Photo: Allen Phillips

cat.no. A1.111

103

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Dorothea Berck (1593-1684), dated 1644

Baltimore (Maryland), Baltimore Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 1938.231

Photo: Mitro Hood

cat.no. A1.112

104

Anonymous Northern Netherlands (hist. region) 1641 or 1648

Portrait of Dorothea Berck, 1641 or 1648

private collection jhr. mr. W.E. van Weede

105

Govert Flinck

Portrait of Dorothea Berck (1593-1684)

A comparison between the portraits by Flinck and Hals is especially instructive [106][107]. The much younger Flinck was already much appreciated in Amsterdam by 1647, when he painted the portrait of Joseph Coymans. The unmoved face of the well-groomed wealthy man and his elaborate hairstyle give an impression which strengthens Hals’s facial study. While Hals liked to depict facial features in movement and with distinct emotions, in this portrait, the sitter seems to gaze away and express a lack of interest. His aloofness is observed with great clarity in the area around the eyes and in the raised eyebrows. The attitude of the female sitter in the companion piece is in clear contrast with this, as she turns a pensive and kind gaze towards the viewer [109]. In Flinck’s painting she does not appear as open and accessible [108]. Other than Hals’s firmly positioned Dorothea Berck with her elegantly gloved hand, Flinck’s sitter toys with her cuff in a slightly awkward manner. The integration of body language and facial expression obviously was Hals’s strength and not Flinck’s.

106

Detail of fig. 101

Govert Flinck

Portrait of Joseph Coymans, 1647

sale Zürich (Koller), 16-21 September 2013, lot 3064

107

Detail of fig. 102

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Joseph coymans, 1644

Hartford, The Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art

Photo: Allen Phillips

108

Detail of fig. 105

Govert Flinck

Portrait of Dorothea Berck, c. 1647

sale London (Sotheby’s), 3-4 July 2013, lot 161

109

Detail of fig. 103

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Dorothea Berck, 1644

Baltimore Museum of Art

Photo: Mitro Hood

Many contemporary patrons had themselves portrayed multiple times. A recurrent reason were the multiple marriages, as many women died in childbirth. But also wedding anniversaries, significant birthdays, or a promotion to an important office gave rise to commission a renewed representation. Many repeated portraits also arose out of the group portraits of guardsmen and regents, such as two of the three portraits of Michiel de Wael (1596-1659) (A1.22, A1.30, A2.12). Several patrons seem to have tested their portrait appearance by employing different painters, similar to dress rehearsals.

A comparison between the appreciation of Hals and that of his younger Haarlem colleague Pieter de Grebber demonstrates a difference in favour of the latter, who rarely painted portraits and focused mainly on historical subject matter. Since the writings of Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472) and his followers, ‘Istoria’ or ‘history’ had become the collective term for all representations of human endeavour and emotion. The higher regard for depictions of historical, philosophical and religious subjects was expressed in De Grebber's commissions for altarpieces in the great churches of Bruges and Ghent, as well as for large-scale, decorative pictures in several palaces owned by stadtholder Frederik Hendrik (1584-1647), such as Huis ten Bosch and Het Oude Hof.7 In this context, the Frisian stadtholder Willem-Frederik of Nassau-Dietz (1613-1664) travelled to Haarlem twice in 1648 to visit the workshops of Pieter de Grebber, Salomon de Bray and Caesar van Everdingen (c. 1616/1617-1678). Hals would have benefited greatly from such an honour and even more from the resulting princely commissions, but portraits were not in the same league and lacked the instructive moral value of presenting global historical and mythological events. Hals's teacher Karel van Mander (1548-1606), ‘[…] who had tried his hand at portraits himself, referred to portrait painting in his Schilder-Boeck of 1604 as a “sijd-wegh der Consten” (sideway of the arts), that artists chose merely for profit’.8

De Grebber was a bachelor who had become a prosperous house-owner through his profession as an artist. His parents could live with him, while Frans Hals and his family had to make do with a succession of rented accommodations. De Grebber wrote a treatise himself about ‘Rules of art which draughtsmen and painters need to heed’ and maintained contacts with musicians and music theoreticians.9 Accordingly, he was praised by the Haarlem historians and poets Theodorus Schrevelius (1572-1649) and Samuel Ampzing (1590-1632), as well as by the Leiden painter Philips Angel (c. 1618-afer 1664) in his Lof der Schilder-Konst of 1642.10

The portraitist and history painter Jan de Braij (c. 1626/27-1697) could for some time enjoy similar success, while he received important commissions for allegories and group paintings from the town of Haarlem, that allowed him to pay off the construction of a house in eight years between 1676 and 1684. This house was adjacent to another building he had already inherited from his parents. The excellent powers of observation and artistic expression of this educated painter can be admired particularly in his portraits. The most comprehensive cultural-historical monograph of recent years has rightly been devoted to his oeuvre.11 Among the keenly observed likenesses by Jan de Braij, the Portrait of Andries van der Horn [110] is of particular interest, since it depicts a similar perspective and lighting as that by Frans Hals of 24 years before [111]. A watercolour copy by Warnaar Horstink (1756-1815) [112] renders this long inaccessible painting by De Braij, probably somewhat lighter in colouring and sharpers in the facial features, yet demonstrating an observation of facial movement comparable in intensity to that of the face painted by Hals. Hals’s incredibly assured accents stand out in comparison, but also De Braij’s acute psychology. It is possible that Hals’s portrait was chosen as a model by De Braij, consciously or as a request by the sitter. The body posture and the composition based on diagonals are also indebted to Hals.

The work of the aforementioned portrait painters in Haarlem remained inspired by tradition and followed rules that were first formulated in Van Mander’s Schilder-Boeck of 1604. Nevertheless, Hals's creative example left recognizable traces in individual pictures by his fellow painters from Haarlem and Amsterdam, amongst which are a number of single portraits by Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck. Hals's manner of structuring his militia pieces by using separate groups, and his compositional use of flags and sashes are echoed in the excellent group portrait of the Officers and sub-alterns leaving the Calivermen’s headquarters in Haarlem of 1630, that has traditionally been attributed to Hendrick Pot.12 However, the planar style and rendering of the draperies are very close to Pieter Soutman’s portrait of the Beresteyn family in the Louvre,13 and therefore an alternative attribution to Soutman seems plausible, even more so since Soutman had just returned to Haarlem by 1630.

Hals's rendering of the facial expression of a sitter about to speak, of expressive listening and of various turns towards other figures as well as towards the viewer, were imitated at a high level of quality by the Amsterdam portrait painter Nicolaes Eliasz. Pickenoy (1588-1650), most evidently in his group pictures of the early 1630s and in the Banquet of the civic guardsmen under the command of captain Jacob Backer and lieutenant Jacob Rogh of 1632.14 Finally, there was a younger contemporary of Hals in Haarlem whose brilliant powers of observation created ‘living features’, but who left very few examples of these. This was the draughtsman and copper engraver Cornelis Visscher (c.1628/29-1658), said to have been trained by Pieter Soutman and a member of St Luke's guild in Haarlem from 1653 onwards. His portrait drawings display vibrant facial features and expressive eyes similar to Hals's pictures [113].15

The display of a small picture (‘een tronike’ – a head study) by Hals in the boardroom of the guild of St Luke in The Hague in July 1663 demonstrates that even colleagues from outside Hals’s home town were impressed by his painterly skills. This particular painting was given on loan by the Haarlem-born portraitist Jan de Baen (1633-1702).16 Six years later he sold it, probably rather due to the attraction of the subject than to an interest in its maker. This being said, Dudok van Heel has pointed to one particular Hals element that most struck a chord with his colleagues: the flag-bearer from the Meagre Company [114], which had resounded not only with Van Gogh but already with Rembrandt. The latter’s Standard-Bearer of 1636 [115] copies the appearance of the distinctive man set against the light background of the flag and transposed – not to say demonised – it with surrounding dramatic light flashes. This demonstrates an acute awareness of Hals's painting, while at the same time it shows Rembrandt's unresponsiveness to Hals's brilliance of representation and painterly virtuosity. Rembrandt took only few elements from Hals's composition and used them for a symbolic emphasis that was entirely his own.17

110

Jan de Braij

Portrait of Andries van der Horn (1600-1677), dated 1662

Luxembourg, Musée National d'Histoire et d'Art

111

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Andries van der Horn (1600-1677), dated 1638

São Paulo, Museu de Arte de São Paulo, inv./cat.nr. MASP.00185

Photo: Google

cat.no. A1.93

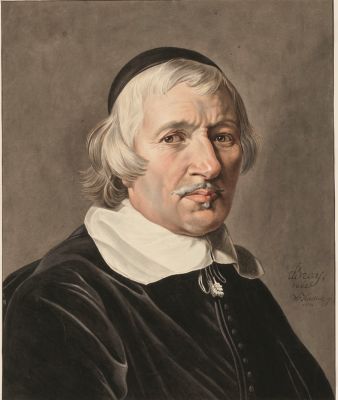

112

Warnaar Horstink after Jan de Braij

Portrait of Andries van der Horn (1600-1677), dated 1814

Haarlem, Noord-Hollands Archief, inv./cat.nr. NL-HlmNHA_53013853

113

Cornelis Visscher (III)

Portrait of Jan de Paep

Paris, New York City, art dealer Haboldt & Co.

114

Detail of cat.no. A2.11

Frans Hals (I) and Pieter Codde

Militia company of district XI, 1633-1637

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

115

Rembrandt

The standard-bearer, dated 1636

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

Notes

1 Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen, Portrait of Cornelia Strick van Linschoten, 1654, oil on canvas, 118 x 90 cm, Enschede, Rijksmuseum Twenthe.

2 ‘[…] meesterlijk en breed van behandeling’. Sale Amsterdam (Jeronimo de Vries), 9 September 1851, lot 198.

3 Ekkart 1979, p. 118.

4 De Winkel 2012, p. 144, 147-149.

5 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 82-83, fig. 39-40, the female portrait listed as dated 1641..

6 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 82.

7 Currently known as Paleis Noordeinde.

8 London/The Hague 2007-2008, p. 17.

9 De Grebber 1649.

10 Angel 1642, p. 52-53.

11 Veith 2011.

12 Attributed to Hendrick Pot, Officers and sub-alterns leaving the Calivermen’s headquarters in Haarlem, 1630, oil on canvas, 214 x 276 cm, Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. os i-285.

13 Pieter Soutman, Portrait of the Beresteyn family: Paulus van Beresteyn (1588-1636) and his wife Catherina Both van der Eem, with their six children and two servants, c. 1630/31, oil on canvas, 167 x 241 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv.no. RF 426.

14 Nicolaes Eliasz. Pickenoy, Banquet of the civic guardsmen under the command of captain Jacob Backer and lieutenant Jacob Rogh, 1632, oil on canvas, 198 x 531 cm, Amsterdam Museum, inv.no. SA 7313

15 Cf. Habraken 2012, p. 352 and two drawings in the Amsterdam Museum: Portrait of possibly Cornelis Guldewagen, red and black chalk on paper, 269 x 215 mm, inv.no. TA 10363; Portrait of a Haarlem clergyman, black chalk on parchment, 289 x 227 mm, inv.no. TA 10364).

16 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 412.

17 Dudok van Heel 2012, p. 5-6.