3.7 Patrons, supporters, maecenases

The situation with regard to commissions remained variable for Hals, especially when it came to group portraits. Hals’s contemporaries judged differently from us. They aimed for an impressive pictorial representation for the present and future and found it no less with Hals’s competitors as with him. The town historian Theodorus Schrevelius (1572-1649), for example, wrote in 1648 about the large group painting Officers and sub-alterns of the Calivermen's civic guard by Pieter Soutman (c. 1593/1601-1657) [116] that he ‘also painted an entire platoon for eternal memory’.1 This expresses a fact about the meaning of portraiture which has become unimaginable in the modern world, but which we need to consider as a historical reality if we want to understand the meaning of Netherlandish group portraits. In Hals’s world, the political events of the present were still essentially read as an outcome of a process of salvation history, which also encompassed actions by local decision-makers. This was particularly true after the breakaway of the northern Netherlandish provinces from Spanish rule under King Philip II and the subsequent long struggle for independence. The civic guards were the protectors of liberty and justice in the municipalities; the paintings of their voluntary leaders symbolizing the strive for freedom and public spirit. They were destined for the large meeting and practice rooms of the two municipal militias and should make every member of the community’s leading group visible. Frans Hals turned these group meetings into a visual experience, in the same way as he understood his individual portraits. His approach was that of a distant viewer, as we all are today. But his patrons saw their pictorial projects not as a visual attraction but rather as a medium of repeated encounter with many individuals who needed to be captured as exactly as possible, as in a large photo album.

Between 1616 and 1639, Hals had created five much admired group portraits of the leaders of the Haarlem civic guards. In 1642, two more such large projects were planned, the portraits of the officers and sergeants of the Calivermen's and St George’s civic guards. Yet these commissions did not go to Hals but to Pieter Soutman. A total of 13 figures had to be painted on an enormous canvas of 2 x 4 meters [116], respectively 17 figures on a canvas measuring 1,8 x 4 meters [117]. Hals knew many of the sitters or their nearest relatives; some he had even portrayed himself. At the time, Hals was at the height of his creative powers. It is inconceivable with today’s criteria why he was not given the opportunity. It demonstrates that in these cases he lacked sufficient advocates. Both group portraits were inspired by Hals’s militia paintings in their composition and in many motifs, but also by the Regents of St Elisabeth’s Hospital (A1.102) which he had only recently completed. Some of the guardsmen represented had sat for Hals’s paintings themselves. We are therefore in a position to compare their portraits. For example, the brewery owner and treasurer Michiel de Wael (1596-1659) [118] is not only prominently depicted in the centre of Soutman’s 1642 Officers and Sub-Alterns of the St George civic guard, but also in Hals’s earlier group portraits of 1626/1627 and 1639 [119][120]. However, in Soutman’s painting, not only are the proportions uneven – some faces behind De Wael are larger even though they are further away – but a clear structuring of the picture plane is lacking, which would have emphasized his appearance as it is in Hals’s paintings. He is less in action, and it may be that his friends and family found his likeness well represented.

116

Pieter Soutman

Officers and sub-alterns of the Calivermen's civic guard, Haarlem, dated 1642

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv./cat.nr. OS I-313

117

Pieter Soutman

Officers and sub-alterns of the Saint George civic guard, c. 1642

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv./cat.nr. OS I-314

118

Detail of cat.no. A1.22

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Michiel de Wael, c. 1625-1626

Cincinnati, Taft Museum of Art

Tony Walsh Photography

119

Detail of cat.no. A1.30

Frans Hals (I)

Banquet of the officers of the St George civic guard, c. 126-1627

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

120

Detail of cat.no. A2.12

Frans Hals (I) and workshop

Officers and sergeants of the St George civic guard, 1639

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

Some other portraits in Hals’s and Soutman’s group portraits show a mode of representation which is partly similar and partly different. Soutman appears as an able painter of individual portraits who was, however, not capable of staging a group appearance nearly as well as Hals. Soutman’s faces are well imagined, three-dimensional renderings which would be a much easier template for a sculptor to work from than some of Hals’s painted heads. Soutman lit his portraits more evenly, yet in an ensemble of figures this makes the overall impression seem monotonous. From Soutman’s 1642 group portrait of the Calivermen [116], the following portraits were extracted whose sitters were also painted by Hals:

- colonel Cornelis Backer (†1655) [121][122]

- captain Johan van Clarenbeeck (1601-1642) [123][124]

- sergeant Sivert Sem Warmond (†1647) [125][126]

121

Detail of fig. 116, Colonel Cornelis Backer

Pieter Soutman

Officers and sub-alterns of the Calivermen’s civic guard, 1642

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

122

Detail of cat.no. A2.10, Captain Cornelis Backer

Frans Hals (I) and his workshop

Meeting of the officers and sergeants of the Calivermen civic guard, c. 1632-1633

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

123

Detail of fig. 116, Captain Johan van Clarenbeeck

Pieter Soutman

Officers and sub-alterns of the Calivermen’s civic guard, 1642

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

124

Detail of cat.no. A1.102, Johan van Clarenbeeck

Frans Hals (I)

Regents of St Elisabeth’s Hospital, c. 1640-1641

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

125

Detail of fig. 116, Sergeant Sivert Sem Warmond

Pieter Soutman

Officers and sub-alterns of the Calivermen’s civic guard, 1642

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

126

Detail of cat.no. A1.102, Sivert Sem Warmond

Frans Hals (I)

Regents of St Elisabeth’s Hospital, c. 1640-1641

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

Taking into consideration the differences in perception illustrated here and the resulting downgrading of Frans Hals, an earlier project gains new importance. This was the commission in 1633 for the group portrait of 16 full-length portraits of officers and other guardsmen of the XIth district of Amsterdam’s crossbowmen’s civic guard (A2.11): a highly prestigious commission. As Dudok van Heel describes the historic situation, the painters who would have been first choice, that is Nicolaes Eliasz. Pickenoy (1588-1650) and Thomas de Keyser (1596-1667), were already fully occupied with the execution of two commissions each for large group paintings. The young Rembrandt (1606-1669) – who had only just completed his first portrait commissions in Amsterdam from 1631 and who had finished The anatomy lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp in 1632 – had not yet proved himself in a large-scale composition of a standing group of civic guardsmen.2 It was the art dealer and agent Hendrick Uylenburgh (c. 1587-1661) who had brought Rembrandt to Amsterdam, and it was probably he whom the guardsmen of the eleventh district consulted for their commission. In that case, it would have been the influential Uylenburgh who recommended Hals, also offering studio space in his own workshop and accommodation in his house.3 Uylenburgh’s activity thus becomes highly interesting. It would not have been merely the engagement of a less expensive painter from Amsterdam’s surroundings, but rather an unconventional initiative in favour of a talent he deemed superior earlier than others – if this all proved to be the case.

When Hals received commissions, it was in competition with his fellow painters. He needed to agree to all conditions with his patrons, just as an architect or decorator does today. Nobody ceded an inch. There was neither charity nor generous patronage in play, as the representations were required in the way they were created with talent and effort. Otherwise, there were other painters who could supply something similar in appearance with comparable effort. There were only a few patrons that proved to have a noticeable preference for Hals. In first place was the merchant, diplomat, author, and cartographer Isaac Abrahamsz. Massa (1586-1643). The fact that he also served as godfather for Hals’s daughter Adriaentje indicates a personal connection. Hals owed four portrait commissions to Massa, from 1622 to 1635 [127][128]. Among them, the large double portrait of Massa and his wife Beatrix van der Laen (1592-1639) of 1627 (A2.8) was certainly a private, and in its motivation, unusual commission far beyond the scope of a typical portrait representation. In this case, a commitment to Hals’s artistic approach is demonstrable. Whether Massa should be referred to as a ‘patron’ or a ‘maecenas’ could only be decided on the basis of the commission and payment details, which are not preserved.Other than specialists for other genres, portrait painters had immediate and longer access to their socially more elevated models and their environment through the sittings. Entire careers were built upon this, bearing in mind court painters like Hans Holbein (c. 1497/1498-1543), Lucas Cranach (1472-1553), Titian (c. 1488/1490-1576), Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), or Velázquez (1599-1660). Unlike those and unlike Dutch portraitists oriented towards courtly commissions like Michiel van Mierevelt (1566-1641) or Gerard van Honthorst (1592-1656), or fashionable portrait painters of the Amsterdam higher society, Frans Hals seems to have maintained a clear distance to most of his sitters. Apart from the fact that portraits were tied to specific individuals, his critical observation and unaccommodating style of painting were probably the reasons why he did not find long-term support. Nevertheless, he continued to encounter individuals who were almost obsessed by their pictorial representation. Two very different examples can illustrate the eagerness for pictures which is unimaginable today but offered good business to painters like Hals. The viewer who sees Hals’s full-length portrait of the cloth merchant Willem van Heythuysen [129], finds a close relation 75 years later in the closely related posture of the Sun King Louis XIV by Hyacinthe Rigaud (1659-1743) [130]. Unlike in the later picture, in Hals’s portrait the artificial and arranged character is more than obvious. What he depicts is an idea, a mind image. The cloth extended behind the figure with its long folds is clearly only a prop, but it generates a visual effect of light and dark lines emanating from the face and upper body of the figure. The exaggerated theatricality and the cool gaze convey the staged character of the whole and a certain role distance on the part of the sitter. While the portrait of the French king is seen from a great distance and transports a glorifying message of a political reality shaped by destiny, Hals’s painting is a theatrical event. It offers a realistic wide angle view from a close viewpoint, with the viewer's eye level set at the horizon seen on the left and the downward gaze of the sitter. It is a performance here and now, a glamorous show and nothing more. The cloth merchant Heythuysen greets his guests as someone demonstrating his ability and his wealth, which includes a stunning painting of himself.

127

Details of:

cat.no. A1.13 Frans Hals (I), Portrait of Isaac Abrahamsz. Massa, 1622, Chatsworth House, The Devonshire Collections

cat.no. A2.7 Frans Hals (I), Portrait of Isaac Abrahamsz. Massa, 1626, Toronto, Art Gallery of Ontario, Photo ©AGO

128

Details of:

cat.no. A2.8 Frans Hals (I), Portrait of Isaac Abrahamsz. Massa and Beatrix van der Laan, c. 1627, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

cat.no. A4.1.11 workshop of Frans Hals (I), Portrait of Isaac Abrahamsz. Massa, c. 1635, The San Diego Museum of Art, gift of Anne R. and Amy Putnam

129

and Pieter de Molijn Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Willem van Heythuysen (?-1650), c. 1625-1626

Munich, Alte Pinakothek, inv./cat.nr. 14101

cat.no. A2.6

130

Hyacinthe Rigaud

Portrait of Louis XIV in armour, dated 1701

Madrid (city, Spain), Museo Nacional del Prado, inv./cat.nr. P002343

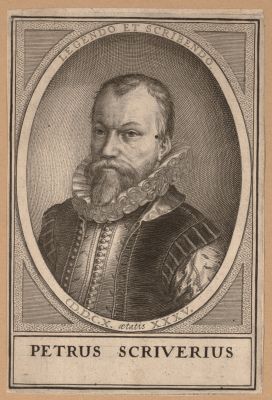

A similar self-representational ambition was expressed by the abovementioned historian and writer Petrus Scriverius (1576-1660), for whom Hals made two small-scale portrait paintings (A4.1.4, A4.1.5) and one portrait engraving in 1626 [131], almost at the same time as the Heythuysen portrait. The occasion was the joint 50th birthday of the couple. While most engraved portraits of scholars were made in their old age, usually shortly before or just after their death, Scriverius began early to have his likeness recorded and make it ‘for memory immortal’ (as Theodorus Schrevelius noted in a letter to Scriverius, 17 June 1618).4 He did so at least three times, once in 1611 at the age of 35 by Willem van Swanenburg (1580-1612) [132], then for his 50th birthday in 1626 by Frans Hals, and finally in 1649 at the age of 74, when he had himself painted by Pieter Soutman and the painting replicated in an engraving [133]. A striking element is the motto ‘LEGENDO ET SCRIBENDO’ which appears in all three engravings, probably to be completed with ‘my life is dedicated to reading and writing’. ‘Scribendo’ alludes to the name ‘Scriverius’. In the engraving of 1611, a further motto is provided: ‘LARE SECRETO’, that is ‘in the retreat of his residence’. This expresses something similar to the Latin verses under the engraving of 1626: ‘Here you see the face of him who, shunning public office / makes the Muses at personal expense. / He loves the privacy of his own home [...]’,5 which he nevertheless publicized in a print run of an engraving. Extensive eulogies of his person can already be found in the book with portraits and biographies of Leiden professors, published in 1617 by Johannes van Meurs (1579-1639), where the 1611 engraving is reproduced.6 A later eulogy was the 21 lines of verse contributed by Hugo de Groot (1583-1645) – probably on request – to the portrait engraving of 1649. Scriverius was adept at placing this image and text with discerning addressees. He added it to his series of engravings with verses on four famous figures of recent history as portrait of the author and fifth ‘persona’.7

The wealthy private scholar thus satisfied his needs for self-representation vis-à-vis an educated audience. The autograph modelli for Hals’s portraits of the Scriverius couple are not preserved, neither are the later ones by Soutman. But the versions painted on panel by Hals’s workshop (A4.1.4, A4.1.5) and the partial copy after Soutman in the Frans Hals Museum [134], together with the engravings, give an approximate idea. It is hard to say how Scriverius saw Hals’s abilities, since he commissioned his, up to then most representative, portrait to Soutman and had an ambitious engraving made after it. But everything was relegated to second place after the magisterial representation of Scriverius by Bartholomeus van der Helst (c. 1613-1670) [135]. The magnificent portrait is dated 1651 and was created on the occasion of the sitter’s 75th birthday. The picture was probably intended for the sitter’s family, for tragically, Scriverius lost his eyesight from 1650 and was unable to see during the last years of his life. He would have thus also been prevented from seeing that Van der Helst’s image was once again surpassed by another portrait. Ironically, the wealthy Scriverius was probably one of the first buyers of paintings by Rembrandt, the 1625 Stoning of St Stephen and the History Painting of 1626.8 He could not anticipate that his son Willem Schrijver (1608-1661) would ask the same Rembrandt to execute a large-scale portrait historié, known as Jacob Blessing the Children of Joseph [136], where the figure of the blind patriarch Jacob was a symbolic reference to Scriverius on whose profile his image was based. This painting, for which Scriverius sat for a last time, achieved what he had intended through his portrait engravings. It made him ‘immortal for memory’. Hals played only a minor role in this history of Scriverius portraits. It is not clear whether Scriverius was familiar with the total of five Hals portraits which his son Willem had received from an inheritance from the Soop family in 1657. These were listed as such in an estate inventory after Willem Schrijver’s death in 1661.9 Three years after the decease of Petrus Sciverius in 1660, his books and paintings were posthumously sold at auction in Amsterdam. Included in this sale were also the three small-scale depictions of musicians by Frans Hals, which were listed in Schrijver’s inventory of 1661.10

The career of Frans Hals was modest, and he was denied the attention which his Amsterdam colleague Rembrandt did attract. The same is true for the acceptance or rejection of Hals’s works. His analytical gaze and his sober assessment of what pictures are able to convey did not meet the highflying expectations of many of his contemporaries. Hals avoided pathos and remained largely within the confines of his narrow genre, the making of portraits. The great subjects of global history are absent from his oeuvre. Nevertheless, some of Hals’s paintings are enormously impressive, no less than the masterworks of his fellow painters.

Hals was less conventional than his colleagues. The contemporary representatives of society certainly deserve all the more credit for not only recognizing a special quality in Hals’s colourful civic guard portraits but also for appreciating his intense individual portraits that departed from the more traditional, smooth formula. The town-fathers of Haarlem’s regard for Hals's services to the community were ultimately expressed in several clear gestures. One of these was the permission to include his self-portrait in the group portrait of the officers and sergeants of the St. George civic guard of 1639.11 Furthermore, the painters' guild suspended the old and impoverished painter’s annual contribution, amounting to six stuivers. Finally, from September 1662 the elderly Hals was granted outstanding support by the mayors of Haarlem, providing him 200 guilders per annum, in addition to rental support and firewood – an amount far above the general level of poverty relief and only slightly below the annual income of 250-300 guilders that was normal for a carpenter or bricklayer. The municipal secretary in Haarlem received a remuneration of 272 guilders in 1625, with an additional clothing allowance of 27 guilders. When Hals's widow was granted support on 26 June 1675, after having requested it repeatedly, the sum amounted to a weekly stipend of 14 stuivers, which made 36 guilders per annum.12

The benefits that Frans Hals received clearly indicate the city’s intention to honour an esteemed citizen. However, they differed from the appreciation shown to grand masters of the arts who had already been famous during their lifetime. A striking example from Haarlem is the engraver and history painter Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617): when he was buried in the church of St Bavo in 1617, the bells rang for half an hour. And when Hals's teacher Karel van Mander (1548-1606) was buried on 13 September 1606 in the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam, 300 people joined the funeral procession. Finally, it was said that for the burial of the Hals’s fellow painter Pieter Soutman on 21 August 1657, the bells of St Bavo rang for two hours.13 For Frans Hals, no such extraordinary funerary rituals have been reported.

Hals was buried on 1 September 1666 in a prestigious burial site in the choir of St Bavo – an honour which he had inherited through his first wife’s grandfather, town councillor Nicolaas Joppen Gijblant. Hals was buried in Gijblant’s grave, yet without having his name added to the stone slab. This was only done many years later in 1918. Finally, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Frans Hals Museum in 1962, a new slab was put on the grave, solely stating ‘Frans Hals’[137].14 For today’s visitor to St Bavo, it now seems as if the name Frans Hals had been known and honoured continuously from the time of his death to the present. In this respect, we have to consider that a named grave was a privilege of the upper classes in the 17th century. Rembrandt was also buried anonymously in 1669, in the Amsterdam Westerkerk. In comparison with his much more famous colleague, Hals was honoured with a final resting place in a named grave very near the front of the church.

131

Jan van de Velde (II)

Portrait of Petrus Scriverius (1576-1660), after 1626

Great Britain, private collection The Royal Collection, inv./cat.nr. 670167

© His Majesty King Charles III 2023

cat.no. C9

132

Willem van Swanenburg (I)

Portrait of Petrus Scriverius (1576-1660), 1609-1610

The Hague, RKD – Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis (Collectie Iconografisch Bureau)

133

Cornelis Visscher (III) after Pieter Soutman published by Pieter Soutman

Portrait of Petrus Scriverius (1576-1660), 1649 (dated)

The Hague, RKD – Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis (Collectie Iconografisch Bureau)

134

after Pieter Soutman

Portrait of Petrus Scriverius (1576-1660)

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv./cat.nr. OSI-666

135

Bartholomeus van der Helst

Portrait of Peter Scriverius (1576-1660), 1651 (dated)

Leiden, Museum De Lakenhal, inv./cat.nr. 1445

136

Rembrandt

Jacob blessing Manasseh and Ephraim, dated 1656

Kassel, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel), inv./cat.nr. GK 249

137

the plaque on the grave no. 56 in the choir of the church of St Bavo, Haarlem

Notes

1 ‘[…] dat hij een geheel Corporaelschap oock heeft gheschildert tot een eeuwige gedachtenis’. Schrevelius 1648, p. 384. See also: Biesboer/Köhler 2006, p. 608.

2 Rembrandt, The anatomy lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, 1632, oil on canvas, 169.5 x 216.5 cm, The Hague, Mauritshuis.

3 Dudok van Heel 2017, p. 17-19.

4 Haarlem 2013, p. 137.

5 ‘Illivs ora vides, qvi pvblica mvnia vitans / Aonias proprio vindicate aere deas, / secretosqve lares amat’. See also: Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 185.

6 Van Meurs 1617.

7 Quatuor Personae; the four figures being Magdalena Moons (1541-1613), Francisco de Valdez (†1580), Jan van der Does (1545-1604) and Louis de Boisot (1540-1576).

8 Rembrandt, The stoning of Saint Stephen, 1625, oil on panel, 89,5 x 123,6 cm, Lyon, Musée des Beaux-Arts, inv.no. A 2735; Rembrandt, History Painting, 1626, oil on panel, 90 x 122 cm, Leiden, Museum de Lakenhal, inv.no. 460.

9 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, doc. 166.

10 Sale Amsterdam, 8 August 1663, no. 21.

11 Hals became a member of the St George civic guard in 1612, serving as a musketeer in the third – and later on second – company of the third corporalship until 1624.

12 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 45, 50, 57, note 14 (German edition), docs. 170, 171, 174, -178, 181, 185, 189.

13 Biesboer/Köhler 2006, p. 37, 159, 231, 310.

14 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, doc. 183.