A1.111 – A1.121

A1.111 Frans Hals, Portrait of Joseph Coymans, 1644

Oil on canvas, 83.8 x 69.9 cm, inscribed on the right: AETA SVAE 52 /1644

Hartford, The Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, inv.no. 1958.176

Pendant to A1.112

Joseph Coymans (1591-1677) was born in Hamburg on 1 august 1591 as the son of Balthasar Coymans (1555-1634), native of Antwerp, who had settled in Hamburg by 1585. A year after Jospeh’s birth, the family relocated to Amsterdam, where they later on founded the celebrated Coymans trading company. In 1616, Joseph married Dorothea Berck (1593-1684) in Dordrecht. The couple moved to Haarlem by 1620, where they initially lived next door to Paulus van Beresteyn (1588-1636) (A2.1). Their trading activities led to the Coymans family becoming one of the wealthiest and most illustrious families of Haarlem: in 1631, Joseph was taxed on a capital of 400.000 guilders, for instance.1 Slive mentioned that the marriage of the Coymans-Berck couple’s daughter Isabella Coymans († 1689) to Stephanus Geeraerdts († 1671) on 4 October 1644 in Haarlem, may have been the occasion for the present portraits.2 A few years later, Hals created the glorious representations of Isabella and her husband (A1.119, A1.120).

The pair of portrait pendants of Joseph Coymans and Dorothea Berck form an outstanding document for the history of portraiture, since an entire group of ambitious portraits can be attributed as commissions from these patrons. There are the pictures dated 1641 and 1648, formerly in Huis Bingerden.3 And, there is the fine Portrait of Joseph Coymans by Jacob van der Merck (1610-1664), signed and dated 1641.4 Finally, there are the equally ambitious portraits of Joseph and Dorothea by Govert Flinck (1615-1660), dated 1647.5

A1.111

© Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art / Photo: Allen Phillips

A1.112

© The Baltimore Museum of Art: The Mary Frick Jacobs Collection, BMA 1938.231

photograph by Mitro Hood

A1.112 Frans Hals, Portrait of Dorothea Berck, 1644

Oil on canvas, 83.8 x 69,9 cm, inscribed, dated and monogrammed center left: AETA SVAE 51/ AN° 1644 / FH

Baltimore, The Baltimore Museum of Art, inv.no. 1938. 231

Pendant to A1.111

Dorothea Berck (1593-1684) was the wife of the enormously wealthy merchant and banker Joseph Coymans (1591-1677), whom she had married in 1616. She was the daughter of Johannes Berck – squire of Alblasserdam, burgomaster of Dordrecht and ambassador to England, Denmark and Venice – and Erkenraadt van Brederode.6 In this portrait, she appears in expensive clothing, yet open and ready to establish contact, in contrast to her reserved and somewhat self-important husband. Both portraits – sadly separated today – were painted in muted colors, with the man’s likeness dominated by the contrast between skin tones and black-grey shades of the clothing, and the female one by silver-grey to white tones. In the female portrait, the juxtaposition of the flesh tone of the left hand and the ivory shade of the glove of the right hand is supremely delicate. The virtuosity in the rendering of the gloves is typical for Hals, who wonderfully captured the distorted creases and flat fingertips in both pictures.

As stated above, from a historical point of view, it is interesting that both paintings can be compared to further contemporary portraits of the same sitters. Two other portraits of the Coymans couple from the 1640s have been preserved, which the faces are recognizably the same, yet the representation is mechanical and lacking in expression.7 From the point of view of perspective, the female portrait of 1641 is nearly identical with Hals’s present 1644 painting. Slive quite rightly rejected the suggestion that Hals’s portrait had been painted after this earlier picture and not after the model.8

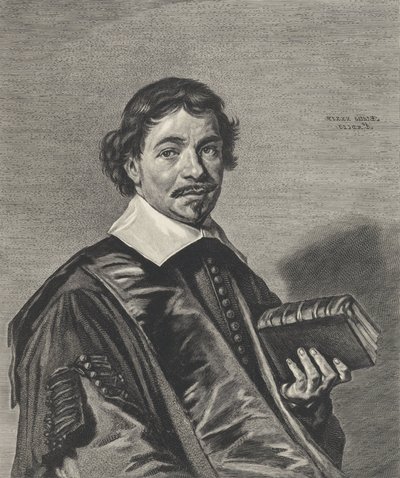

A1.113 Frans Hals, Portrait of Adriaen van Ostade, c. 1645

Oil on canvas, 94 x 75 cm

Washington, National Gallery of Art, inv.no. 1937.1.70

This painting was offered at a 1919 Sotheby’s sale in London as a self-portrait of the Haarlem painter Nicolaes Berchem (1621/1622-1683), indicated by an old inscription and a label on the reverse.9 By the end of that year, what was by now recognized as a Frans Hals was already owned by Andrew W. Mellon (1855-1937), the founder-collector of the National Gallery of Art in Washington. 50 years later, the sitter was identified as Hals’s pupil Adriaen van Ostade (1610-1685). This identification is plausible based on, firstly, the resemblance to Ostade’s likeness in the group portrait of the De Goyer family, and, secondly, to that in a mezzotint by Jacob Gole (c. 1660-1724), inscribed ‘Adrianus van Ostade’, which reproduces a lost portrait that Ostade’s pupil Cornelis Dusart (1660-1704) had painted of his teacher (C43).10 Dusart used the face of the present portrait as a model and dressed his master with a long curly wig, a scarf slung around the neck and a kimono-style dressing gown, known as ‘Japonsche rock’. In the present picture he is presented as an elegant gentleman, comparable in bearing and gestures to Hals’s Portrait of Paulus Verschuur of 1643 (A1.107). Wheelock pointed to the gestures of the removed glove in both paintings, presenting an open and unarmed hand for greeting.11 In each of the two portraits, Hals sketched the hands in comparable virtuoso style. Ostade’s age of about 34 years and the still quite formal style of painting fit into the mid-1640s.

A1.113

Photo courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

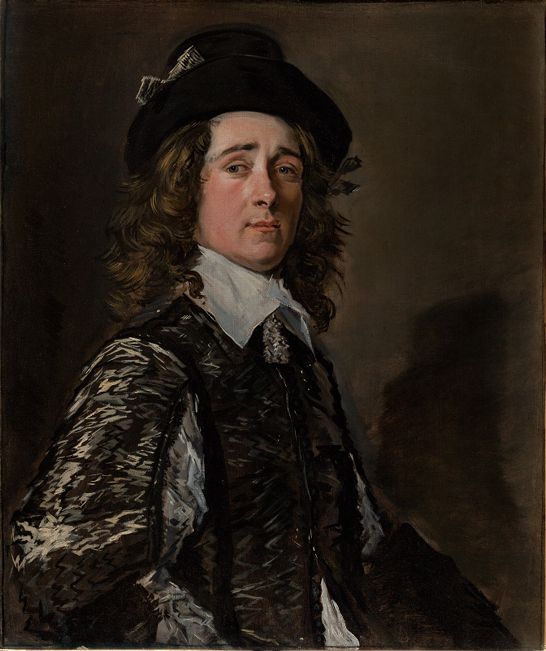

A1.114 Frans Hals, Portrait of Willem Coymans, 1645

Oil on canvas, 77 x 64 cm, inscribed and dated center right: AETA SVAE 22 / 1645

Washington, National Gallery of Art, inv.no. 1937.1.69

Willem Coymans’s (1623-1678) taste for luxury is indicated by this portrait commission at the young age of 22. His side-facing posture with the arm over the back of the chair was adopted by Hals in several paintings and conveys a relaxed form of self-representation. While the arm akimbo only appears as a dark circle in the background, the proper right arm pushed forward offers a decorative color scheme, with its slashed sleeve in embroidered brocade and the pleated shirt. With his shoulder-length hair, large white collar and hat with a pompom, the youth peers out at the viewer in a blasé and ostentatiously unimpressed manner. The coat of arms on the wall behind him identifies him as a member of the wealthy Coymans family. Willem’s father Coenraet († 1659) was a cousin several times removed of Joseph Coymans (1591-1677) (A1.111) and had also moved from Amsterdam to Haarlem in the 1640s. From his posthumous estate inventory that was drawn up on 24 April 1660, we know that Frans Hals and his colleague Pieter de Molijn (1595-1661) were assigned the valuation of 29 paintings in his collection. Willem Coymans had commissioned the inventory together with his brother-in-law Johan Fabry.12

The present portrait, with its restricted palette, is very well preserved with a restricted palette and displays the compositional skills and ease of painterly technique that Hals used to configure his types of expression. The most virtuoso detail is the hand that is subtly touched by the light. Once this shape, delineated with very few brushstrokes, has been consciously perceived, any suggestion of attributing clumsy hand areas such as in the Portrait of a man (A4.3.17) to the same painter is out of the question.

A1.114

Photo courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

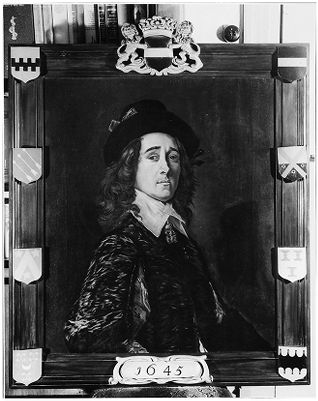

A1.115 Frans Hals, Portrait of Jasper Schade, c. 1645

Oil on canvas, 80 x 67.5 cm

Prague, Národní Galerie Praha, inv.no. O 638

It is a peculiarity in Hals’s portrait production that he painted two 22-year-old dandies within a very short period of time and in almost the same format: Willem Coymans (1623-1678) from Haarlem (A1.114) and Jasper Schade (1623-1692) from Utrecht. Both wear suits made of black gold brocade with slashed sleeves and hats set at an angle on top of their wide flowing locks. A gold-colored bow adorns young Jasper’s hat. A letter from his uncle, dated 7 August 1645, warns against Jasper’s exorbitantly high tailor’s bills. His ‘proposition d’un habit de 300 francs’ refers to a sum comparable to three quarters of the annual income of an experienced craftsman, and was presumably also equivalent to an average income on which a painter like Hals would have to manage.13 This standing young man in Hals’s portrait seems even more arrogant than his contemporary Willem Coymans; leaning back, his scrutinizing gaze conveys pure contempt.

Jasper, who came from a prestigious patrician family, became deacon of a protestant college in Utrecht in 1666, in 1672 he was representative for Utrecht to the States-General and in 1681 president of the Utrecht court of justice. The hereditary provenance of the portrait is extraordinary and illustrates magical thinking, in spite of the unparalleled material character of the representation. At the beginning of the 1650s, Jasper Schade had a superb country house built near Utrecht, called Zandbergen. Hals’s portrait was hung over the door to the salon (‘middenkamer’). With the house, it passed to Jasper’s son Gaspar Cornelis Schade († 1701), and after the latter’s death, to his brother-in-law Jacob Noirot (1670-1740). From 1740, when Noirot sold the house, until the purchase by the Beuker family in 1865, the house had nine different owners. Even though the picture is not mentioned in any of the sales documentation, it seems to have always been sold with the house – according to legend, the house would fall down if the picture were removed. Descendants of the Beuker family stated that their ancestor, who bought the house in 1865, had also bought the portrait in the process. He, in turn, sold the painting to Pieter Ernst Hendrik Praetorius (1791-1876) on the condition that the latter would provide a copy as replacement [1].14 The original went to the collection of John Waterloo Wilson (1815-1883), from where it was sold at auction in Paris in 1881.15 Prince Johann II of Liechtenstein (1840-1929) purchased it shortly thereafter and donated it in 1890 to the Galerie Rudolphinum in Prague.

Apart from eight family coats of arms, the date of 1645 had been noted on the frame of the original, as well as on that of the copy. Sadly, the original frame was lost in the meantime. The well-preserved original painting was cleaned in 2011.

Just like several other contemporaries – Theodorus Schrevelius (1572-1653), Petrus Scriverius (1576-1660) and Joseph Coymans (1591-1677) – Jasper Schade had himself painted not only by Frans Hals but also subsequently by other artists. A comparison with the 1654 portrait by Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen (1593-1661) confirms the fashionable inclinations of the wealthy patron [2]. Cornelis Jonson was a painter born in England, from a Netherlandish family. He was successful painting the portraits of the English aristocracy and had been appointed court painter in 1632 by King Charles I of England (1600-1649). During the English civil war he had moved to Holland. From 1646 to 1652 he worked in Amsterdam, then in Utrecht. The pair of three-quarter portraits of Jasper Schade and his wife Cornelia Strick van Linschoten (1628-1703) shows an aristocratic self-image, devoid of Hals’s critical distance.16

A1.115

1

Pieter Ernst Hendrik Praetorius

Portrait of Jasper Schade (1623-1692), c. 1865-1870

Private collection

cat.no. B20

2

Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen (I)

Portrait of Jasper Schade (1623-1692), dated 1654

Enschede, Rijksmuseum Twenthe, inv./cat.nr. 698a

A1.116 Frans Hals, Portrait of Johannes Hoornbeeck, 1645

Oil on canvas, 79.5 x 68 cm, inscribed and dated lower right: AET. SVAE/ 27./1645

Brussels, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, inv.no. 2245

The Haarlem-born Johannes Hoornbeeck (1617-1666) was a highly educated scholar who spoke thirteen languages, and one of the most influential theologians of his time. It is not coincidental that Max Weber referred to Hoornbeeck’s 1663 publication Theologiae Practicae in his important book Die protestantische Ethik und der Geist des Kapitalismus.17 As an orthodox Calvinist, Hoornbeeck was a believer in the idea of predestination that was already recognizable in this world. In 1644 he was appointed professor of theology at the University of Utrecht, where he was to become rector in 1650/1651. In 1654 he moved to Leiden University.

In Hals’s portrait, Hoornbeeck wears the academic gown and holds a book in his hand, while his hidden thumb appears to mark a page. The reversed engraving by Jonas Suyderhoef (1614-1686) of 1651, refers to Hoornbeeck as a man of the church and the university in Utrecht (C45). Later versions of the print mention him as a professor in Leiden.18 The sitter appears at peace with himself, and his face seems almost unmoved. The left eyebrow is slightly raised and the lower lip protrudes a little, giving an impression of collecting one’s thoughts. The highlights on the black silk and the sketchy light rendering of the hand suggest a peripheral dissolution of the visual perception and refer back to the central focus of the sitter’s face. In accordance with Hoornbeeck’s high social status, a number of copies of his portrait have been preserved.19

A1.116

© Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten van België (Brussel), photo: J. Geleyns

A1.116a After Frans Hals, Portrait of Johannes Hoornbeeck, c. 164520

Oil on panel, 30.8 x 24.7 cm

Sale London (Christie’s), 1 July 2025, lot 5

The appearance of a smaller version of the portrait of theologian Johannes Hoornbeeck (1617–1666) has reignited the debate about copies that are attributed to Frans Hals and the paintings with small formats that correspond to contemporary copper engravings. Repetitions were traditionally required for portraits, as there was often a need for private remembrance as well as for public representation. Such duplicates could be produced by any artist, provided they had access to the original model. Depending on the size and level of detail, they had to have the original in front of them for many days or weeks in a well-lit place. In painters' workshops, such copying was usually a task for the assistants, as the master could produce a new work with the same or even less effort. Based on what is known to date, this also applies to Frans Hals and his workshop, even though not all experts agree.

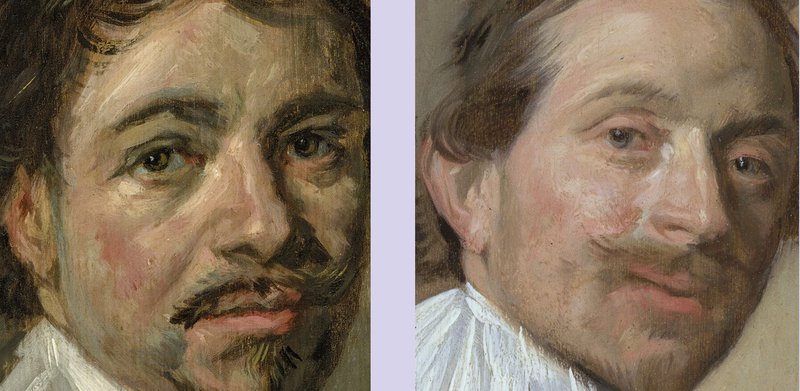

This is demonstrated by the discussion surrounding this present small portrait of Hoornbeeck, which was recently auctioned at Christie's in London. It was described in the catalogue entry as a repetition by Hals himself, based on the 1645 portrait that is now in Brussels (A1.116). At the same time, it was identified as the design for the 1651 engraving by Jonas Suyderhoef (C45), which is slightly larger, but has the same format when the edges of the copperplate are taken into account [3]. This attribution is remarkable. Up to my knowledge, there are no other copies by Hals himself in his oeuvre, and only one painting by his own hand that directly served as a model for an engraving of the same format, which is the portrait of Jean de la Chambre (A1.87) executed in 1638. With this one exception, all other comparative works mentioned in the catalogue entry can be recognized as being of lesser quality. This can be clearly observed from the examples below. By comparing detailed photographs, the still divergent attribution situation can be brought to a more easily comprehensible level.

A1.116a

3

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of Johannes Hoornbeeck, 1651

copper engraving, 332 x 259 mm

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. RP-P-OB-60.733

cat.no. C45

cropped and reversed

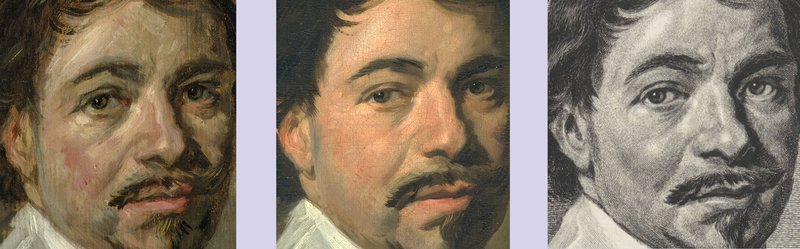

The small panel – which has long been in private ownership – corresponds in its depiction to Hals's considerably larger portrait on canvas. However, the assessment of the newly discovered painting as an autograph repetition by Frans Hals cannot be upheld when the execution is studied in detail [4]. Many details differ here: the size of the eyes, the eyelids, the creases in the eyelids, the eyebrows, the nostrils, the bridge of the nose and the forehead wrinkles above it, the ears, and the mouth area. Why would Hals, such a precise observer, have created such a crude reproduction? Instead of the clear application of paint in the facial areas and the restriction to specific accents, there is a jumble of blurred brushstrokes. The concentration on a few significant details, so typical of the master, is missing. What we see here is a superficial imitation that deviates from Hals’s his handling of the brush. One possible objection to the comparison made here concerns the difference in size between the artworks. In the Brussels painting, the face measures approximately 20 cm in height, while in the London version it measures only approximately 7.5 cm.

4 Details of

- cat.no. A1.116a, after Frans Hals (I), Portrait of Johannes Hoornbeeck, sale London (Christie’s), 1 July 2025, lot 5

- cat.no. A1.116, Frans Hals (I), Portrait of Johannes Hoornbeeck, 1645, Brussels, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, © Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten van België (Brussel), photo: J. Geleyns

- cat.no. C45, Jonas Suyderhoef, Portrait of Johannes Hoornbeeck, 1651, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum - reversed

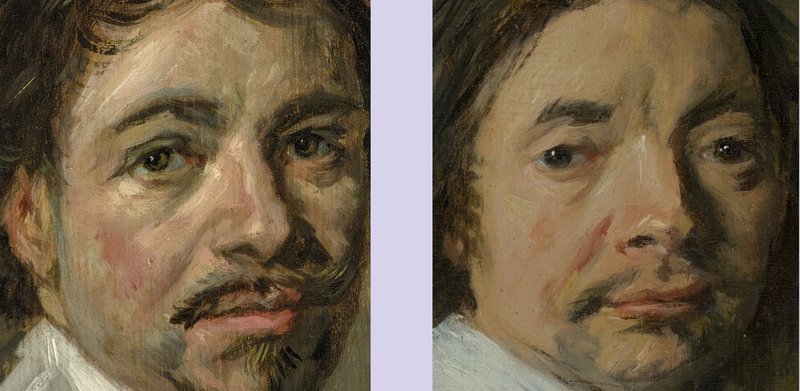

If one looks for contemporary examples of similarly small-format faces in a similar perspective and lighting, the only comparable work is the portrait of Jean de la Chambre, with the height of the face measuring about 6 cm. Comparison of these two small-sale faces clearly shows the differences between Hals’s light and airy manner of execution – with rhythmic diagonal brushstrokes concentrated on a few accents – and the blurred and smudged application of paint in the present painting [5].

5 Details of

- cat.no. A1.116a, after Frans Hals (I), Portrait of Johannes Hoornbeeck, sale London (Christie’s), 1 July 2025, lot 5

- cat.no. A1.87, Frans Hals (I), Portrait of Jean de la Chambre, 1638, London, National Gallery

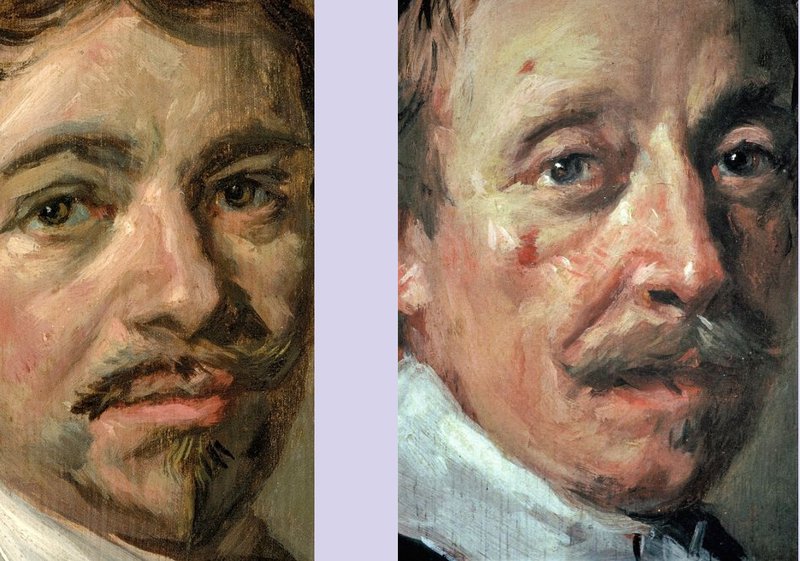

Christie’s auction catalogue also points out the stylistic relationship between the London painting and Hals' later small-scale portraits. ‘(…) this portrait of Hoornbeeck anticipates a number of similar works painted in the second half of the 1650s or shortly thereafter. These include the Portrait of a preacher of circa 1657-60 (A3.60); the Portrait of a man of circa 1660 (A1.131) and the Portrait of a preacher of circa 1660 (A4.3.53)‘. Two of these examples from Hals's later years are included here. They illustrate a fundamentally different painting style, where Hals's paint application has lost none of the concentration and discipline that we see in his earlier works. The examples of Hals' late style show that his technique was not a laborious description, but rather the application of colourful passages onto into the painted surface. Hals created patterns of colours and light that aesthetically enhance the appeal of the depiction. In doing so, he combined the application of paint with rendering the outlines of the facial expressions, which he put down psychologically accurately in a few sweeping lines. None of this ability to emphasize aesthetic observations can be found in the London Hoornbeeck portrait [6].

6 Details of

- cat.no. A1.116a, after Frans Hals (I), Portrait of Johannes Hoornbeeck, sale London (Christie’s), 1 July 2025, lot 5

- cat.no. A1.131, Frans Hals (I), Portrait of a man, The Hague, Mauritshuis

The difference in painting technique is visible even when compared to paintings from Hals’s workshop. The portrait in Boston (A4.3.53), possibly executed by Hals's son Frans Hals (II), shows the loose application of paint in patches of colour that is characteristic of the Haarlem master, but none of the tentative brushstrokes that are present in the London painting [7]. Highlights and patches of colour are merely dabbed on, but the application is uncertain and haphazard, almost shaky.

7 Details of

- cat.no. A1.116a, after Frans Hals (I), Portrait of Johannes Hoornbeeck, sale London (Christie’s), 1 July 2025, lot 5

- cat.no. A4.3.53, workshop of Frans Hals (I), possibly Frans Hals (II), Portrait of a preacher, Boston, Museum of Fine Arts

A comparison of details also shows that the small panel cannot have been the model for the engraving. It is unlikely that the conclusive clarity of the face, which corresponds so precisely to the larger-format portrait in Brussels, could have been developed from the unclear small-format model. The erratic white and pale-green brushstrokes found there do not appear in the engraving. In principle, no reduced intermediate model was necessary for the production of engravings if a representative large-scale version was available. The copyist could record its contours onto transparent paper, divide it into a grid, and transfer it to the corresponding squares on the copper plate. The similar format of the engraving and the panel painting therefore rather suggests that the painting was created after the print, with the outline of the engraving being transferred to the picture panel with a tracing device and then reversed.

It is not only in this one case that the differences in painting style argue against the assumption that such a small-format painting would have been a ‘modello’, or template, used for the production of an engraving, or a larger-scale painting. This assumption recurs frequently in the literature on Frans Hals, referring to all of his small oil paintings for which engravings of the same or similar format have been preserved. One example of this is the portrait of René Descartes (1596-1650) (A4.1.15a, C46) [8]. As was probably the case, the portrait sketch directly based on the sitter was likely executed in oil paint on paper. This was cheaper than painting on canvas or wood and dried more quickly. It was thus ideal for use by engravers, as well as for painters, functioning as a design for a more finished painting on canvas or panel. Its disadvantage was its low durability, which explains the loss of most of these portrait sketches. Based on this primary design, the final composition could be developed further in the studio in the absence of the sitter. Their presence was neither necessary for the depiction of the hands and clothing – as can sometimes be seen in the sketchy execution of these areas. However, these aspects of artistic practice have not been considered thus far.

8 Details of

- cat.no. C46, Jonas Suyderhoef, Portrait of René Descartes, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum – reversed

- cat.no. A4.1.15a, workshop of Frans Hals (I) or after Frans Hals (I), Portrait of Descartes, c. 1649, Copenhagen, SMK – National Gallery of Denmark

With respect to the Descartes portrait, Seymour Slive wrote: ‘(...) the Copenhagen portrait can be accepted as the modello Jonas Suyderhoef used for his excellent reversed engraving of the portrait, and we can assume the print shows the state of the Copenhagen portrait before it was cut’. And: ‘(…) the possibility that an original life-size painting based on the Copenhagen sketch may turn up one day cannot be excluded either’.21 These assumptions are untenable when one compares the face of Descartes in Suyderhoef's engraving with his alert gaze in the painting. It goes against the practice of drawing and painting to attribute the highly precise representation of a distinctive physiognomy to such an information-poor derivative as the panel in Copenhagen. To do so, Suyderhoef would have had to be a far better artist than the creator of the template he based himself on. No one can arrive at a clearer and more psychologically coherent representation, solely from memory. That would mean keeping the uniqueness of a particular perspective, a particular moment of movement, or a particular lighting situation for the complex appearance of a face retrievable in memory. How difficult it was to depict such a challenging model and how rarely it was successful, can be seen in the various contemporary portraits of Descartes.22 This observation is evident in this case, as it is in close examination of most of the other alleged ‘models’. With the exception of the portrait of Jean de la Chambre, none of the small oil paintings stand up to close comparison with authentic works by Frans Hals, nor with the qualified engravings.

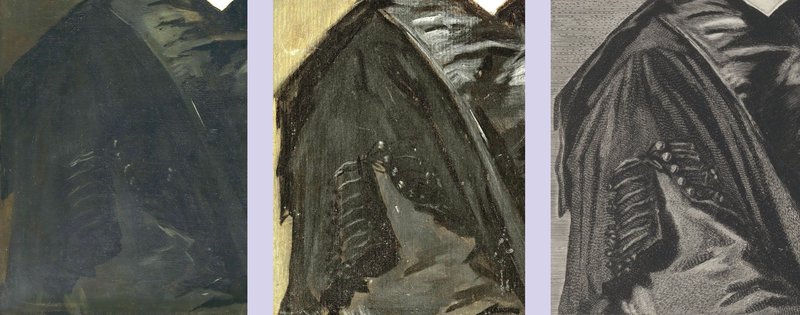

Finally, there is the question of how to classify the London version of the Hoornbeeck portrait. Due to its many similarities, it can be described as a relatively accurate copy of the original in Brussels. The panel on which it has been painted can be dated to around 1639, following recent dendrochronological analysis. When the painting as it is visible today, was applied to it, is independent of this date and appears to be younger in style. Only a pigment analysis could reveal anything additional here. However, the well-preserved surface of the paint layer already has documentary value. This is because, probably long after the Brussels painting was completed, a significant change was made to the sitter’s clothing – for unknown reasons. The left upper arm and, with it, almost half of the figure were painted over with smooth black paint, blurring the previously visible modelling. Knowing this, the figure looks as if his arm has been amputated. The resulting ‘dead’ area was enlivened by a few faint reflections and scattered grey brushstrokes. The flattened surface is visible in a post-exposed detail image and is reproduced exactly in the London copy [9]. In turn, Suyderhoef's engraving shows what Hals's portrait originally looked like and how convincingly the figure was depicted. The plasticity of his chest and arm, and the clearly imaginable folds of the heavy fabric falling from the shoulder, give the figure an emphatic presence. The split sleeve, decorated with buttons and small ribbons also adds to the liveliness of this section.

9 Details of

- cat.no. A1.116, Frans Hals (I), Portrait of Johannes Hoornbeeck, 1645, Brussels, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, © Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten van België (Brussel), photo: J. Geleyns

- cat.no. A1.116a, after Frans Hals (I), Portrait of Johannes Hoornbeeck, sale London (Christie’s), 1 July 2025, lot 5

- cat.no. C45, Jonas Syderhoef, Portrait of Johannes Hoornbeeck, 1651, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum - reversed

It is unclear when and by whom the arm and chest areas were reworked. Whoever was responsible for this, their style does not show any stylistic consistency with the Frans Hals workshop. This assessment also applies to the present copy, which clearly deviates from Hals’s painting technique. The 2025 catalogue entry mentions recent dendrochronological examination of the panel, suggesting that the panel dates from after c. 1639. Yet, the use of an older or newer support does not necessarily indicate the age of the applied paint. This kind of analysis merely provides a ‘terminus ante quem non’, not more. Finally, ‘The fact that the painting and print overlay with almost no discrepancies’, as is mentioned in the sale catalogue, is worth commenting on. This observation only confirms the correspondence between the two representations. Usually, a copyist copied the outlines of an engraving, using these as a basis for the rest of the artwork.

A1.117 Frans Hals, Portrait of a man, c. 1645-1646

Oil on canvas, 79.5 x 58.5 cm

Sale New York (Sotheby's), 28 June 2019, lot 16

The painting was already listed by Moes in 1909, Hofstede de Groot in 1910 and Bode & Binder in 1914, but it was only known to the art world through a dark illustration in Valentiner's Klassiker der Kunst of 1921 and 1923.23 It was offered at auction in London in 1969, where it remained unsold.24 Slive had not included it in his catalogue of original works by Hals and published it in 1974 as a presumed copy after a lost original.25 In my 1971 essay Frans Hals und seine Schule I had suggested Jan Hals (c. 1620-c. 1654) as the author and had accordingly excluded the picture from my monograph of 1972.26 I had overlooked the catalogue of the 1969 London sale, yet when I saw it in 1973, I contacted the owners via the auction house. An examination at the Swiss Institute for Art Research confirmed my presumption that it was in fact a damaged and dirty original by Hals. Several cracks ran across the center of the picture surface, indicating a probably deliberate attack. The restoration that Dr. Thomas Brachert undertook in 1973-1974 established the original components and could reduce the discoloration that was caused in particular by the darkening of a binding agent. The paint losses could be filled in by retouching. Afterwards, the paint layers were revealed again in their uniform coloring and with Hals’s typical brushwork. The extensive recovery of the original; appearance is described in the 1975 restoration report by Thomas Brachert and me.27 The execution of the facial features, but also the cool grey tonality is in keeping with Hals’s style of the mid-1640s. The collar with the large lace scallops is related to the collars in the earlier portraits dated 1643 (A1.107, A1.108).

A1.117

Photograph Courtesy of Sotheby’s, Inc. © 2023

A1.118 Frans Hals, Portrait of a man, c. 1646-1648

Oil on canvas, 68 x 55.4 cm, monogrammed center right: FHFH

Washington, National Gallery of Art, inv.no. 1937.1.71

Thrown down in a dashing manner, this portrait depicts a young man with his arm over the back of a chair, a position that was frequently employed by Hals. Similarly to the preceding Portrait of a man (A1.117), the sitter is also fitted closely into the frame, respectively emphasized in a close-up perspective. As noted by Arthur Wheelock, there are loose brushstrokes beyond the representational purpose in the painterly execution that would support a later date than 1645.28 These include the stripy light reflections on the nose, cheek and lip, as well as the summary treatment of the tonality in the collar and the knob of the chair. The unusual monogram is part of the original paint layer and has not been explained to date.

An instructive reference for knowledge about Frans Hals in the 18th century is the list that the great collector and connoisseur Horace Walpole (1717-1797) compiled in 1736, of paintings in his father’s houses. Here, and also in the Aedes Walpolianae printed in London in 1747, the present picture is described as a self-portrait: ‘Francis Halls, Sir Godfrey Kneller’s Master, a Head by himself’.29 We know that Hals must have looked differently, especially in his sixties. Nevertheless, Walpole must be taken seriously as a source of information about the internationally famous English court painter . Gottfried Kneller (1646-1723). Kneller became a painter at age seventeen in Holland and was sent for training not only to Ferdinand Bol (1616-1680) and Rembrandt (1606-1669), but also to Hals, according to Walpole.30 He must have become familiar with Hals’s work in the last years of his activity. The present portrait that is associated with this reference was copied in an engraving in 1777 by Jean-Baptiste Michel (1748-1804), which is inscribed as ‘Francis Halls’ [10].

A1.118

Photo courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

10

Jean-Baptiste Michel

Francis Halls, 1777 gedateerd

Philadelphia (Pennsylvania), Philadelphia Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 1985-52-26131

A1.119 Frans Hals, Portrait of Stephanus Geeraerdts, c. 1646-1648

Oil on canvas, 114.5 x 86.5 cm

Antwerp, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, inv.no. 674

Pendant to A1.120

On 4 October 1644 Stephanus Geeraerdts († 1671) from Amsterdam married Isabella Coymans († 1689), who had been born in Haarlem. The couple seems to have settled in Haarlem, where Stephanus bought a splendid house in the Koningstraat for 12.800 Carolus guilders – approximately ten times the price of a small house like the ones where Hals lived.31 At some point between the two dates the couple commissioned a pair of portraits from Frans Hals. The result is an unusual pair of paintings, whose sitters relate to each other well beyond the pictures’ frames. The portly husband is seated on a chair and slightly turned towards the viewer. As if in greeting, he has taken off his right glove, holding it in his proper left hand. His other hand is stretched out towards his wife. Her body is turned away from him, but her head and right arm are turned towards him while she offers a rose. Both smile lovingly at each other. A dispute among art historians concerned the question whether the rose was adopted here as a symbol of love or of transience.32 In my opinion, there is no exclusive symbolic meaning in the motifs of the 17th century, but rather connotations, which can be manifold. A thought about love need not exclude the consciousness of transience. ‘All in vain’ does not preclude a devotion to life.

A1.119

Collectie KMSKA - Vlaamse Gemeenschap

A1.120

A1.120 Frans Hals, Portrait of Isabella Coymans, c. 1646-1648

Oil on canvas, 116 x 86 cm

Private collection

Pendant to A1.119

Bianca Du Mortier described the luxurious and worldly fashion in which Isabella Coymans († 1689) is dressed.33 In Hals’s commissioned portraits, she is the only woman who displays décolletage. She is adorned with elaborate lace fabrics, bows, decorative ribbons from silver lace, and pearls. The hair falling to the side in curls, as well as the open expression on her face – which is relaxed beyond a discreet hint of a smile – go against the traditional decorum and performance of propriety. There was no room for laughter in a Calvinist sense of duty and sanctity in everyday life; a ‘spiritual human being’ should restrain his laughter because Christ never laughed.34 Only a small elite group could afford to display ostentatious luxury and permit itself the freedom of unconventional behavior. Isabella came from a family of wealthy merchants and bankers. ‘The marriage contract stipulated that the bridegroom would bring to the match a sum of 100.000 guilder, landed property and other effects. Isabella's parents gave her a dowry of 30.000 guilders’.35

Isabella’s parents had already been painted by Hals in 1644 (A1.111, A1.112). But in comparison with the dignified style of clothing and the conventional picture expectations of her parents, her portrait, as well as that of her relative Willem Coymans (1623-1678) (A1.114), displays a new and carefree extravagance. This is Hals’s latest female portrait that is unquestionably by his own hand. The loose brushwork of the present picture and its pendant certainly indicate a date later than the 1644 portraits of her parents and the 1645 portrait of Willem Coymans. The estimated date of c. 1646-1648 takes this difference into account, but is also based on the research by Du Mortier that dates Isabella’s clothing around 1644.36 The slashed jacket of Stephanus Geraerdts matches the similarly embroidered jackets in the 1645 Portrait of Willem Coymans (A1.114), and the probably contemporary Portrait of Jasper Schade (A1.115). Might the clothes of the couple not be their wedding attire that they wore at a later stage, similar to the Olycan-Hanemans couple (A1.17, A1.18)?

A1.121 see: A3.53A

Notes

1 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 36, 44 note 135.

2 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 82.

3 Anonymous, Portrait of Joseph Coymans, 1648, oil on panel, dimensions unknown; Anonymous, Portrait of Dorothea Berck, 1641 or 1648, oil on panel, dimensions unknown. Perhaps the date on the latter can also be read as 1647?

4 Jacob van der Merck, Portrait of Joseph Coymans, 1641, oil on canvas, 70.8 x 54.3 cm, Madrid, Soraya Cartategui Fine Art.

5 Govert Flinck, Portrait of Joseph Coymans, 1647, oil on canvas, 75.2 x 62.7 cm, sale Zürich (Koller), 16-21 September 2013, lot 3064. Govert Flinck, Portrait of Dorothea Berck, oil on canvas, 73 x 61 cm, sale London (Sotheby’s), 3-4 July 2013, lot 161.

6 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 44, note 135.

7 Anonymous, Portrait of Joseph Coymans, 1648, oil on panel, dimensions unknown; Anonymous, Portrait of Dorothea Berck, 1641 or 1648, oil on panel, dimensions unknown. Perhaps the date on the latter can also be read as 1647?

8 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3 (1974), p. 82.

9 Sale London (Sotheby’s), 5-6 May 1919, lot 285 (2nd day).

10 Adriaen van Ostade, Self Portrait of Adriaen van Ostade with the De Goyer family, c. 1650-1652, oil on panel, 63 x 51 cm, The Hague, Museum Bredius, inv.no. 86-1946.

11 Wheelock 1995, p. 79-82.

12 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 409, doc. 160.

13 Haarlem 2013, p. 130.

14 Damsté 1985, p. 30-31; Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 306-308.

15 Sale Paris (Pillet), 14-16 March 1881, lot 58 (Lugt 40851).

16 Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen I, Portrait of Cornelia Strick van Linschoten, dated 1654, oil on canvas, 118 x 90 cm, Enschede, Rijksmuseum Twenthe, inv.no. 689b.

17 Weber 1920.

18 Jonas Suyderhoef, Portrait of Johannes Hoornbeeck, 1651, engraving, The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History.

19 For instance: Anonymous, Portrait of Johannes Hoornbeeck, oil on canvas, 65 x 54.5 cm, Utrecht University; Anonymous, Portrait of Johannes Hoornbeeck, oil on canvas, 76.5 x 60.5 cm, Leiden University.

20 This entry was included in August 2025.

21 Slive 1970-1074, vol. 3, p. 90.

22 For instance: workshop of Frans Hals (I), Portrait of René Descartes, oil on canvas, 76 x 86 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv.no. 1317 (A4.1.15); Jan Baptist Weenix, Portrait of René Descartes, oil on canvas, 45.1 x 34.9 cm, Utrecht, Centraal Museum, inv.no. 7386; David Beck, Portrait of René Descartes, oil on panel, 83.5 x 66 cm, Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, inv.no. NMTiP 3000; Anonymous, Portrait of René Descartes, oil on canvas, 67.2 x 57.2 cm, Amsterdam, University of Amsterdam, inv.no. 040.

23 Sale London (Sotheby’s), 26 March 1969, lot 86.

24 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3 (1974), no. D56.

25 Grimm 1971, p. 161.

26 Brachert/Grimm 1975, p. 148-151.

27 Wheelock 1995, p. 83-85.

28 Walpole 1747, p. 40.

29 Walpole 1762-1771, vol. 3 (1763), p. 221.

30 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 37.

31 Boot 1973; Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 322.

32 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 52.

33 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 37.

34 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 52.