A1.24 - A1.34

A1.24 Frans Hals, Two boys singing, c. 1624-1625

Oil on canvas, 66.8 x 52.1 cm, monogrammed lower left: FH

Kassel, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, inv.no. GK 215

The subject matter of Two boys singing and the close-up depiction of half-length figures are derived from painted prototypes that were created in Utrecht. The present picture is close to that of the Singing Boys by Abraham Bloemaert (1566-1651) [1] which was engraved by Cornelis Bloemaert II (c. 1603-1692).1 Comparing the two compositions, Hals’s rephrasing as a coherent composition becomes apparent, joining the two half-length figures in the picture plane and placing the inner contours of the faces in the same diagonal structure as the dominant line of the lute.

The coloring and modelling of the facial features clearly pre-date those visible in Two laughing boys (A1.33) and in the two roundels in Schwerin that were executed c. 1627 (A1.35, A1.36), moving Two boys singing closely to Singing boy with a flute (A1.25). I also concur with Slive’s arguments, that the current painting’s ‘spatial arrangement of the principal figure, the light grey background and the general tonality can be related to the Laughing Cavalier, dated 1624’ (A1.16).2

The pleasing composition has been reproduced many times, without drawing attention to the overpainting that sadly disfigures the boys’ hands, their hair and parts of their clothing. Both the painted variant [2] and the engraving by Wallerant Vaillant (1623-1677) [3] that was in turn based on it, illustrate the original and convincing design of the hands of the boy depicted in front. At an unknown date, the wrongly foreshortened hand of the other boy has been inserted, and the raised hand of the lute player has been partly overpainted. Since then, that hand got damaged on the thumb and the little finger, and the hand on the lute’s neck was equally mangled. Besides, a much too wide bulge of hair was added to the right of his neck. Furthermore, all areas of the hair have been overpainted in a manner which differs from that of Hals. The mezzotint by Vaillant was created after the painted variant (B5). Both show a more recent style of dress, with the white cuffs on the sleeves and the absence of a white collar. The comparison with these artworks also suggests that Two boys singing was cut along the left hand side and that its entire lower right half is covered by overpainting and retouches.

A1.24

© Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister

1

Abraham Bloemaert

Singing boys, c. 1625

Jaarsveld (Lopik), private collection Anna Boom van Jaarsveld

2

Anonymous

Two boys singing, c. 1624-1625

oil paint, panel, 33.5 x 28 cm

Sale London (Sotheby’s), 17 December 1998, lot 367

cat.no. B5

3

Wallerant Vaillant

Two boys singing

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1911-93

cat.no. C12

A1.25 Frans Hals, Singing boy with a flute, c. 1626-1627

Oil on canvas, 62 x 55.2 cm, monogrammed lower right: FH

Berlin, Gemäldegalerie der Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, inv.no. 801A

As argued by Slive, this boy, who is wearing an actor’s costume, is a personification of Hearing.3 The subject matter of half-length figures singing and playing instruments, as well as the hand gesture, are inspired on models by Utrecht artists such as Dirck van Baburen (c. 1592/1593-1624) and Hendrick ter Brugghen (1588-1629). Hals, however, focuses more on the figure’s facial movements, which are also illuminated more strongly. While the Netherlandish Caravaggisti emphasize gestures, Hals rather highlights the psychological action. His observations of moments of hearing were newly stringent and focused on intensely visible instants of facial movement. It is conceivable that he painted the Berlin picture as a more credible and more intensely expressive variant of Ter Brugghen’s Singing boy of 1627 [4].

The moral, philosophical and other connotations of genre paintings of this type were not accidental for the contemporary observer. They were historically determined by the objects in the scene and the associations these triggered in the context of visual communication. If we want to ascertain what Hals and his contemporaries saw when looking at the present picture, there are helpful observations made by Marcus Dekiert in his review of Martina Sitt’s 2003 interpretation.4

The present painting was restored in 1959/1960 at the Berlin Gemäldegalerie by Hans Böhm. His examinations revealed that a strip of canvas, featuring a depiction of a book that was clearly not done by Hals, had later been added to the lower edge [5].5 Today, this strip is covered by the frame. However, it is not clear whether the picture may have included such a motif in the first place. Unfortunately, the above-mentioned restoration obliterated the foreshortened upper arm of the boy, that was originally visible behind the spread hand. This area has now unfortunately become incomprehensible in its appearance. A restoration and clarification of the components would be desirable.

A1.25

Photo: Christoph Schmidt; Public Domain Mark 1.0

4

Hendrick ter Brugghen

Singing boy, dated 1627

Boston (Massachusetts), Museum of Fine Arts Boston, inv./cat.nr. 58.975

5

Cat.no. A1.25, condition prior to restoration

A1.26 Frans Hals, The merry lute player, c. 1625-1626

Oil on panel, 100 x 90 cm, monogrammed lower right: FH

London, Guildhall Art Gallery, City of London Corporation, inv.no. 3725

This half-length figure is an embodiment of Frans Hals’s vibrant momentary observation. It illustrates his adoption of Caravaggesque effects, turning them into formulas of experience with the strikingly visual elements of his figures. As in works by Utrecht painters, such as the 1623 Merry Fiddler by Gerard van Honthorst (1592-1656), or the recently surfaced Violin player with a wine glass from the same year, painted by Dirck van Baburen (c. 1592/1593-1624), the subject is the sensual pleasure of Taste, Hearing and Sight.6 Hals’s composition is a simplified variant of the Young man and woman in an inn, also dated 1623 (A3.3), featuring only the male figure holding up a wine glass. The brightly illuminated face is positioned at the intersection of the picture’s diagonals, with dynamic lines that extend into the fingers and the cuff of the left arm and the contours of the lute’s neck. The ‘internal’ content, derived from the intense external expression, refers to the enchanting but all too transient sensual impulses. Sight and Hearing are prominently displayed with obvious attributes – look at the wonderful reflections in the glass and the lute – but Taste and Touch are also represented, by the wine and the hands holding the glass and lute, respectively. These references to sensory perceptions are amalgamated with the movement of the laughing face and the arbitrariness of the incoming sunlight, which forms a bold single impression.

As already mentioned a number of times in the art historical literature, Hals’s genre paintings featuring singers, musicians and actors from the 1620s are based on the creations of Utrecht painters, especially Hendrick ter Brugghen (1588-1629), Gerard van Honthorst, Dirck van Baburen and Abraham Bloemaert (1566-1651). They already adopted almost the entire repertory of the gestures we see in Hals’s half-length figures, as well as their combination with symbolic iconography. However, Hals’s compositions are noticeably closer to the observation of reality. They seem less contrived and eccentric and – particularly in their loose brushwork – anticipate a snapshot-character.

The provenance of the present painting has been confused several times with that of a copy, formerly in the private collection of Sir Edgar Vincent, Esher, Surry. In addition to this copy, Slive lists four further copies after The merry lute player’s head.7

A1.26

Photo: City of London Corporation

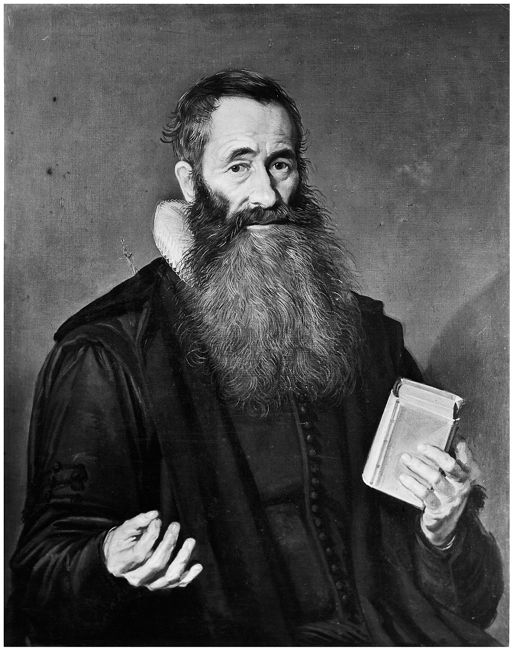

A1.27 Frans Hals, Portrait of Michiel van Middelhoven, 16268

Oil on canvas, 87 x 70 cm

Formerly Paris, private collection A. Schloss

Pendant to A1.28

The pastor Michiel Jansz. van Middelhoven (1562-1638) was born in Dordrecht in 1562 and died in Leiden in 1638. He was a priest in Voorschoten, near Leiden and each of his seven sons also became a priest. As the Middelhoven couple married in 1586, the portraits that were completed in 1626 could have been commissioned on the occasion of their 40th wedding anniversary. It is not known if Hals travelled to the patrons or if they came to him in Haarlem. Considering the efforts in craftsmanship and technique at the time, it seems more likely that the paintings were created in the studio.

A1.27

A1.28

© Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon – Calouste Gulbenkian Museum

photo: Catarina Gomes Ferreira

A1.28 Frans Hals, Portrait of Sara Andriesdr. Hessix, 1626

Oil on canvas, 87 x 70 cm

Lisbon, Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, inv.no. 214

Pendant to A1.27

While the husband's gesture of discourse evokes his preaching, the wife's gestures of one hand on her chest while holding a book in her left are the obligatory signals of humility and piety which we often encounter in portraits by Hals and his contemporaries. As in the male pendant, there is a little tension in the woman's facial features: he seems about to speak while she seems to bite back a comment with a slightly suffering expression. It is, however, conceivable that Hals did not perceive this expression as directed in general towards the dominating husband but also as a typical, individual expression of the sitter.

A1.29 Frans Hals, Young man holding a skull (Vanitas), c. 1626

Oil on canvas, 92.2 x 80.8 cm

London, National Gallery, inv.no. NG6458

This monumental painting indicates the culmination of the influence of Caravaggio's (1571-1610) work on Hals, disseminated in Haarlem through the works by Caravaggio's followers in Utrecht. The foreshortened perspective of the tips of the outstretched fingers and the slanting light on the face that is partly left in the shadow contribute to an unexpected momentary expression where everything is different from the ordinary. Hals combined the extreme aspects as adopted by Caravaggio for example in his The Supper at Emmaus, with a fascinating moment in the performance of an actor [6]. As in the Utrecht painters' half-length figures, Hals's youth wears a beret with a feather and a toga-style cloak that indicate his role. The literature about the painting has repeatedly referred to Shakespeare's Hamlet; but it is not clear whether Hals or his patrons and buyers were familiar with this play or not. In 1962, Slive still thought it possible.9 Nevertheless, all authors agree that the Vanitas and Memento Mori theme represented a widely known and universally understood notion. The pulsating life represented by the youth is contrasted in its fleeting transience by the juxtaposition with the skull. Stylistically, this undated single figure is very close to the figures in the Banquet of the officers of the St George civic guard that was probably finished in 1627 but most likely begun in 1626 (A1.30) – both display modelling with strong shadows and energetic movement.

A1.29

6

Caravaggio

The supper at Emmaus, c. 1601-1602

London (England), National Gallery (London), inv./cat.nr. NG172

A1.30 Frans Hals, Banquet of the Officers of the St George civic guard, c. 1626-162710

Oil on canvas, 179 x 257.5 cm

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. OS I-110

The depicted subject is the farewell banquet of the officers of the St George civic guard in Haarlem, for whose headquarters this group portrait was commissioned. The colonel and his three captains are seated at the laid table with their lieutenants, while two ensigns are entering on the right – probably to report that their respective companies are lined up outside.

While the positions of the depicted officers has already been documented in various places at the time the painting was made, their names were only added to a plaque on the frame around 1740, and discrete numbers were written onto the painting for identification. Portraits commemorated persons of importance, therefore the names of servants were only rarely recorded. From today’s perspective, it is to Hals's credit that his representations of the servants are just as full of character as those of the officers. The numbers that were added onto the figures’ clothing by c. 1740 identify them as follows:

1. Aernout Druyvesteyn (1577-1627), colonel

2. Michiel de Wael (1596-1659), captain

3. Nicolaes le Febure (1589-1641), captain

4. Nicolaes Verbeek (1582-1637), captain

5. Cornelis Boudewijnsz. (1587-1635), lieutenant

6. Frederick Coning (1594-1636), lieutenant

7. Jacob Pietersz. Olycan (1596-1638), lieutenant

8. Boudewijn van Offenberch (1590-1653), ensign

9. Dirck Dicx (1603- after 1650), ensign

10. Jacob Cornelsz Schout (c. 1590-after 1627), ensign

11. Arent Jacobsz Koets (†1635), servant [7]

Apart from the usual placement of the sitters according to their ranks in the civic guard company, Hals had to take another demand into account: four of the men had taken part in the hazardous expedition to Heusden in North Brabant, that had seemed necessary in 1625 to ensure the defense against the Spanish troops, and they were to have the four positions in front. The differences between these four men are attractive: the sitting colonel on the left, with a glass in his right hand, the standing ensign next to him, the seated captain turned towards the viewer, and the captain on the latter's right who is presented standing, due to his short height. Six of the persons present were owners or co-owners of breweries; two served as mayor at a certain time; and other sitters held additional public offices.

Hals skillfully arranged his momentary impression of different groups of men in conversation, while only three of them on the right hand side of the composition make eye contact with the viewer. In this area, the heads are rendered smoother and modelled with stronger contrasts between light and dark. They were most likely painted earlier than the faces on the left, which are lighter and painted more loosely. The emptied wineglass held by the seated captain De Wael (2) in the center foreground is a recurring motif in genre paintings by the Hals workshop. The gesture has been interpreted in different ways, most recently by Koos Levy-de Halm as an admonition to temperance.11 Overall, this commissioned group portrait comes very close to the genre subject of a merry company. We must assume that the individual gestures and body postures were read in a similar way as in genre scenes, either as individual allusions and hints – thus transcending our customary perception.

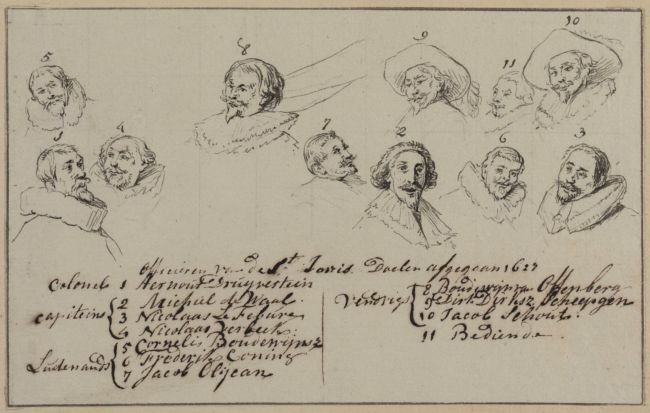

It seems likely that the heads and hands were painted on the basis of individual studies. At least two of the hands in the present picture reappear in other paintings from the Hals workshop: the hand of Michiel de Wael (2), holding a glass recurs in Boy with a lute and a wineglass (A4.2.7) and the open hand of Nicolaes le Febure (3) on the outer right is the same as that in the 1627 Portrait of a man (A4.1.6). The latter hand is either an uncorrected assistant’s contribution, or disfigured by later overpainting The difference in quality between the individual hands in the present group portrait is noticeable and a restorer’s assessment would be useful for further interpretation. For one thing, there are hands (1, Druyvesteyn; 2, De Wael and 7, Olycan) and gloves (8, Van Offenberch and 10, Schout) which were brilliantly developed out of the movement of the brush. These stand in contrast with other softly and hesitantly executed fists and fingers (3, Le Febure; 5, Boudewijnsz. and 6, Coning). The same contrast in execution can be found, yet not quite as distinctly, between some of the faces. While all other heads show the delicate touches of Hals’s brushwork, the faces of Coning (6) and Koets (11) have areas with a less concentrated, more viscous application of paint. The cheek, nose, mouth and chin in the face of Coning (6) are evidently a hesitantly applied design, on which Hals only placed individual finishing accents. The ear appears unfinished. The face, collar and hair of the servant Koets (11) were, however, left in a softer stage of execution, which was probably carried out on the basis of Hals’s portrait study. The comparison between the two styles of painting is particularly obvious between the two heads of Van Offenberch (8) and Koets (11), which were designed in a similar pattern and turn [8][9].

A1.30

7

Wybrand Hendriks

Identification sheet of The Meal of officers of the Saint George civic guard of Haarlem, c. 1780-1820

Haarlem, Teylers Museum, inv./cat.nr. W 042a

cat.no. D19

8

Detail of cat.no. A1.30, head of Boudewijn van Offenberch

Frans Hals (I)

Banquet of the Officers of the St George civic guard, c. 1626-1627

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

9

Detail of cat.no. A1.30, head of Arent Jacobsz. Koets

Frans Hals (I)

Banquet of the Officers of the St George civic guard, c. 1626-1627

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

A1.31 Frans Hals, Portrait of a woman, 1627

Oil on canvas, 86.5 x 70.7 cm, inscribed and dated upper: AETAT SVAE 33 / AN° 1627

Chicago, The Art Institute of Chicago, inv.no. 1954.287

When this painting was restored in 1969, the overpainting depicting a town at dusk in the background was removed [10]. Instead, the back of the chair and a flat back wall appeared, as well as the inscription and the date 1627. The picture was probably trimmed on both sides and along the lower edge; the hand on the left should have been completely visible as a whole. The posture of the sitter suggests that there may have been a male pendant, which is no longer extant.

A1.31

10

Condition prior to restoration

A1.32 see: A2.8A

A1.33 Frans Hals, Two laughing boys, c. 1627

Oil on canvas, 69.5 x 58 cm, signed lower right: FH

Leerdam, Hofje van Aerden (stolen in 2020)

This pair of cheerful boys is likely to be an allegorical representation of one of the five senses, in this instance Sight. However, as outlined by Pieter van Thiel, the ‘kannekijker’ is a traditional symbolic figure representing the mortal sin of intemperance.12 It remains to be seen whether both connotations may have been perceived simultaneously; according to these, using the human senses would be a merely superficial activity of an instinctive nature. Hals’s cheerful momentary observation from daily life retains the underlying subject, but captures sensual experience in an unusually convincing manner. The virtuoso brushwork is an essential contribution to this effect, and is excellently preserved in every detail of this picture. The head of the boy at the rear is closely related to the child’s head in Saint Matthew the Evangelist in Odessa (A1.38).

A1.33

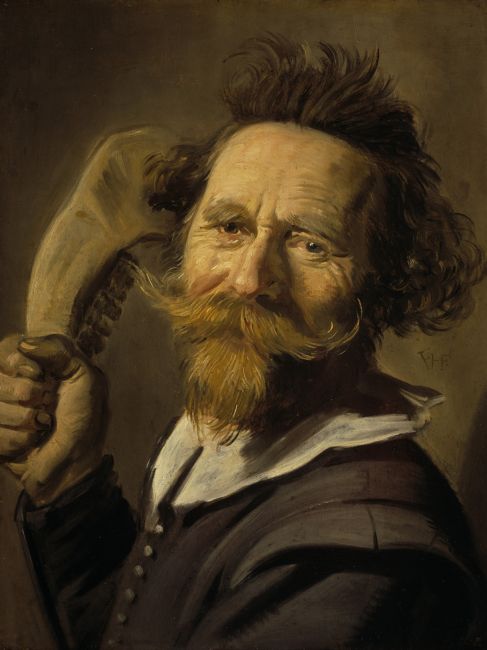

A1.34 Frans Hals, Verdonck, c. 162713

Oil on panel, 46.7 x 35.5 cm, signed center right: F HF

Edinburgh, National Galleries of Scotland, inv.no. NG 1200

Today’s appearance of this painting is the result of a successful restoration which recovered the original details. Based on an early adoption of X-ray examination, the results of the restoration were published as such by the restorer Martin de Wild (1899-1969).14 When the picture was auctioned in 1895 in London, it was described as Man with a wine glass and depicted a merry drinker with a red beret on his head, holding a glass goblet [11].15 By 1927, after the painting had been donated to the museum in Edinburgh some ten years earlier, De Wild was able to remove all later additions. He had established the original composition on the basis of an X-ray photograph and comparison with the reversed engraving by Jan van de Velde II (1593-1641) (C13).

The inscription on the engraving identifies the sitter with his jawbone: ‘This is Verdonck, the brazen fellow,/ Whose jawbone assails one and all./ He cares for none, neither great or small,/ and thus to the workhouse was sent’.16 Similar to the depictions of Peeckelhaering (A1.50, A1.51) and Malle Babbe (A1.103), this painting is part of the portrait-like representations of quirky figures from the margins of society that were presumably created for sale on the open market and not as a commission. The fact that a smaller sized copy was created by an unknown artist shortly after the execution of Hals’s picture (B9); that a second copy was created by an as yet unidentified painter (B10); and that the present picture was published very quickly in an engraving by Jan van de Velde II (C13), which was in turn copied in another engraving; all confirm the public attention attracted by Verdonck’s character and behavior. Pieter van Thiel explained that Verdonck had been a Puritan zealot supporting the strictly pious Mennonites in Haarlem. He was eventually sent to the workhouse by the Haarlem authorities for his inflammatory actions.17 Hals’s Verdonck holds up the jawbone of a donkey or a cow, alluding to the biblical hero Samson, who defeated the Philistines with a jawbone. Accordingly, Verdonck seems to have seen himself as a person who defeated his enemies with words, an interpretation supported by the contemporary Mennonite pamphlet Het Kakebeen.

A1.34

11

Condition prior to restoration

Notes

1 Cornelis Bloemaert II, Singing boys, c. 1625-1628, engraving, 172 x 118 mm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. RP-P-BI-1436.

2 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3 (1974), p. 15.

3 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 172.

4 Dekiert 2004; Haarlem/Hamburg 2003-2004, p. 33-34.

5 The dimensions of the canvas including the later addition are: 68.8 x 55.2 cm.

6 Gerard van Honthorst, The merry fiddler, 1623, oil on canvas, 108 x 89 cm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. SK-A-180; Dirck van Baburen, Violin player with a wine glass, 1623, oil on canvas, 80.4 x 67.1 cm, Clevland OH, The Cleveland Museum of Art, inv.no. 2018.25.

7 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3 (1974), p. 17.

8 Identified and dated on the basis of Jan van de Velde’s (1593-1641) 1626 engraving.

9 Haarlem 1962, no. 18.

10 Considering the serving period of the sitters (1624-1627) and the assumed date of completion in most literary sources (1627) this group portrait was probably painted in 1626-1627.

11 Biesboer/Köhler 2006, p. 478, note 9.

12 Van Thiel 1967-1968, p. 93-94.

13 An old copy is dated 1627.

14 De Wild 1930, p. 230-234.

15 Sale London (Christie’s), 13 July 1895, lot 85, sold for £430 (Lugt 53714).

16 ‘Dit is Verdonck, die stoute gast,/ Wiens kaekebeen elck een aen tast./ Op niemant groot, noch kleijn, hij past,/ Dies raeckte hij in t werckhuis vast’.

17 Van Thiel 1980, p. 132-137.