A1.35 - A1.44

A1.35 Frans Hals, Laughing boy with a wine glass, c. 1627

Oil on panel, ø 38.2 cm, remains of a monogram center right: FHF

Schwerin, Staatliches Museum, inv.no. G 2476

Pendant to A1.36

A1.35

© Staatliches Museum Schwerin

A1.36

© Staatliches Museum Schwerin

A1.36 Frans Hals, Laughing boy with a flute, c. 1627

Oil on panel, ø 38 cm

Schwerin, Staatliches Museum, inv.no. G 2475

Pendant to A1.35

In the 1792 inventory of the ducal collection in Schwerin this pair of pictures is catalogued as made by an unidentified artist. They remained anonymous in the subsequent inventories and catalogues until 1863. In that year, they were finally recognized as works by Frans Hals and registered as such in the collection catalogue.1

The pair depicts the laughter of joyful children as a fundamental utterance of human nature. Two of the typical sensual activities are shown here: Taste and Hearing.2 There are many comparable depictions of the senses in 17th-century painting, sometimes united in one composition – as in the Young man and woman in an inn (A3.3) – sometimes in groups of two to five separate paintings. In those pictures, the sitters are anonymous, as they represent humanity in general, and are thus disregarded as individuals. In this context, Slive refers to Hals’s depiction of the Five Senses that is listed in the inventory of Dirck Thomas Molengraeff (1608-1669) in Amsterdam on 13 January 1654.3 It is not known how many pictures the symbolical depiction of the Senses entailed in this instance. Another series of the Five Sense by Hals consisted of three paintings and is known through a 1661 Amsterdam inventory.4

A large number of copies and variants of the Schwerin pair have been created throughout the centuries, differing in size and format. As Slive put it, ‘most of them are poor caricatures of the original’.5 The Laughing boy with a flute was copied and repeated even more frequently than its pendant.6

In both paintings, the diagonal grain of the panel is visible through the semi-opaque paint layers of the shaded and background areas. Hals and his workshop repeatedly used the support in this way for their genre paintings.7 Semi-opaque paint layers can be observed clearly in the shaded passages in the faces, next to the opaquely colored areas in the highlighted parts. At the transition between light and shade, for example along the nose and cheeks, Hals has added sweeping strokes with a dry brush.

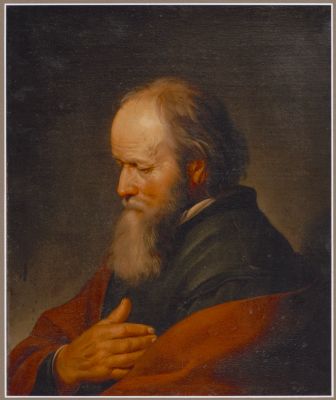

A1.37 Frans Hals, St Luke the Evangelist, c. 1627

Oil on canvas, 70 x 55 cm, remnants of a monogram over the bull’s head: FH

Odessa, Museum of Western and Oriental Art, inv.no. 181

On the first page of Hofstede de Groot's 1910 catalogue raisonné of Frans Hals’s paintings, eight religious works are listed, based on inventories and sale catalogues. These included four paintings of the evangelists, none of which had been identified at the time.8 The more surprising was Irina Linnik’s 1958 discovery of two paintings in storage at the museum in Odessa – catalogued as by an ‘unknown Russian 19th-century artist’ – that she was able to identify as two out of an original set of four evangelists by Hals. The series had been listed in the auction catalogue of Gerard Hoet’s collection that was offered for sale in the Hague in 1760, and subsequently in a 1771 sale in the same city, and finally in an Amsterdam auction of the same year.9 In 1773, they were listed in a hand-written catalogue of the Hermitage, and in 1774 in the printed edition: three works listed as ‘F. Hals’, one as ‘François Gals’, which implies that the cataloguer Minich had probably not heard of the painter Hals.10 The paintings are described as expressive, with spontaneous brushwork. Since then, however, the two pictures located in Odessa, depicting St Luke and St Matthew, have been heavily overpainted and become covered in dirt. A recent removal of the yellowed varnish allows better inspection, but the retouching and overpainting on the faces and hands remain unchanged.

It is not fully known how the two paintings of St Luke and St Matthew ended up in Odessa. In 1812, the Hermitage selected 30 paintings for the decoration of churches on Crimea, including the set of four evangelists by Hals. According to the exhibition catalogue The Return of St Luke. West-European paintings of the 16th -18th centuries from Ukrainian museums, Hals’s evangelist pictures had hung in a church in Odessa until they were lost during the turmoil of the October revolution and the civil war.11 Shortly before the outbreak of World War II, a curator from the Museum of Western and Oriental Art in Odessa is said to have discovered the pictures of St Luke and St Matthew at a flea market and purchased them cheaply for the museum. The paintings had been in storage there until Irina Linnik identified them as works by Hals in 1959.12 In 1964, the painting of St Luke was lent to an exhibition in Moscow, from where it was stolen. The police recovered it the same year from a gang of burglars, together with other artworks. A 1971 Russian crime film, The Return of St Luke, describes the story of the theft.

A1.37

A1.38 Frans Hals, St Matthew the Evangelist, c. 1627

Oil on canvas, 70 x 55 cm

Odessa, Museum of Western and Oriental Art, inv.no. 180

The angel as the attribute of the evangelist St Matthew has been replaced by Hals with a small child looking up. Without knowing the picture’s title, the child might just be understood as moving closer to its grandfather, who is reading aloud. The representation of the evangelists as such worldly figures had been introduced in the Netherlands through the works of Utrecht painters, especially by Hendrick ter Brugghen (1588-1629). This being said, Ter Brugghen’s 1621 evangelists in the town hall of Deventer still are semi-nude elderly men, noble hermits dressed in the antique style, removed from everyday life through highly dramatic lighting.13 In contrast, Hals’s figures have been stripped of all antique connotations, they could just have encountered the viewer in the street. A similarly profane approach appears in a 1621 painting of St Matthew with the angel by Abraham Bloemaert (1566-1651), which shows the half-length figure of an old man with a small child who reaches into his book.14

It is not known who commissioned the series of the four evangelists from Hals. They may have been intended for a private chapel or a hidden catholic church. In this context, Slive referred to the estate inventory of Willem van Heythuysen (1585-1650), in whose house a series of pictures with the four evangelists is recorded as hanging in the hall, albeit in grisaille.15

A1.38

A1.39 Frans Hals, St Mark the Evangelist, c. 1627

Oil on canvas, 68.5 x 52.5 cm, monogrammed upper right: FH

Moscow, Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, inv.no. Ж-4783

In 1955, the estate of a family from Salerno was auctioned at the Hotel Plaza in Rome. The sale included a portrait of a man with a white collar and white cuffs, attributed to Luca Giordano (1634-1705). The buyer, chemist Dr. Silvio Severi, hung the picture in his house in Milan for many years until the young art student Ottorina Tori discovered the monogram and attributed the painting to Frans Hals. After Severi had subsequently sent letters with photographs to all institutions and scholars worldwide who were concerned with Frans Hals, but met with no interest, he offered the portrait for sale in London in 1972, but was equally unsuccessful.16 The author of the present publication saw the illustration in the sale catalogue and convinced the owner to have the painting’s paint layers examined scientifically. It was the observation of the ruffled head of the old man, which made the clumsy overpainting with a patrician’s collar appear so implausible and suggested that there might be a hidden allegorical or religious representation underneath [1]. When the collar and other disfiguring overpaintings were finally removed, the lion behind the figure’s shoulder was revealed. As the size and the model matched that in the picture of St Luke, the experts were now convinced that this painting was originally part of the series of the four evangelists by Frans Hals.

Which models did Hals have for his evangelists? A series such as this would in any case have been a commission, and the representation of the evangelists agreed upon with the patron, regardless of whether the series was intended for a secular or clerical location. Even with a secular approach, the sitters’ bearing and gestures had to be in keeping with tradition. There is no direct model for the type of head and the hand position of St Mark, but Hals may have followed similar types from the artworks of others. For example, there is the disciple on the left of Abraham Bloemaert's (1566-1651) Supper at Emmaus, dated 1622 [2]. Bloemaert painted his highly sculptural and colorful scene for the Catholic church of Sint Bernardus in Haarlem.17 The gestures of the disciple seated to the left of Christ can be found in reverse and turned towards the viewer in Hals’s St Mark the Evangelist. An even closer relationship to the present picture is suggested by the bust of an old man, which is almost identical in size, but undated, and attributed to Hendrick Bloemaert (c. 1601-1672) [3].

A1.39

©The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

1

Condition prior to restoration

2

Abraham Bloemaert

The supper at Emmaus, dated 1622

Brussels, Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten van België, inv./cat.nr. 3705

3

Hendrick Bloemaert

A bearded old man

A1.40 Frans Hals, St John the Evangelist, c. 1627

Oil on canvas, 70.5 x 55.2 cm

Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum, inv.no. 97. PA.48

The long-lost fourth picture of the evangelist series, once owned by Catherine II of Russia (1729-1796), became known to the public through a 1997 London auction.18 In the lower right hand corner there were traces of red paint; leftovers of the Hermitage inventory number, corresponding with the 1774 catalogue published by Minich.19 Another, more recent, number on the lower left edge also corresponds to similar numbers visible on the two paintings now in Odessa.

An overview of all four paintings gives a clear impression of Hals’s profane and worldly approach. His authors of the biblical message to change the world were three coarse old men and one attentive boy looking up, with equally trivial background figures, almost rough mock-ups.

While the areas of faces and hands in the depictions of St John and St Mark were soiled when they were recovered, their original coloring and brushwork has become mostly visible again through cleaning and restoration. In comparison to the two other evangelists, St. Luke and St Matthew, they stand out against the latter’s substantial overpainting, particularly in the faces and hands. A sensitive and skillful restoration of these coarse interventions could result in making the series more visually balanced again.

A1.40

A1.41 Frans Hals, Portrait of an elderly man, c. 1627-1628

Oil on canvas, 115.6 x 91.4 cm

New York, The Frick Collection, inv.no. 1910.1.69

Lead white saponification and earlier cleaning of the facial features caused a loss in opacity in the face of this portrait. The canvas was cut along the lower edge. The lighter shades and the simplification of compact spherical volumes is especially comparable with the representational approach in the Banquet of the Officers of the Calivermen civic guard of 1626-1627(A2.8A). The cut of the clothing is also in keeping with that of the sitters there. The hint of a wary eye, movement of the head towards the viewer, and the mouth that is opening as if about to speak, signal a cautious approach of a sitter who is represented in ponderous self-repose. The man’s hands are comparable to those of Nicolaes Woutersz. van der Meer (1574-1637) of 1631 (A3.19), though the latter’s body is turned more towards the viewer. The illumination of head, hands and body in the Frick painting – designed specifically for round shapes – fits better into the period of the abovementioned civic guard portrait than of later works. The three-quarter turn of the man’s body suggests that the portrait originally had a companion piece. Arthur Wheelock seconded Valentiner's suggestion to consider the 1633 Portrait of a woman (A1.57) – which depicts an elderly seated woman – as the pendant. Yet, the obvious differences in style and manner of execution, as well as the female portrait’s seated position and different viewing angle would argue against the hypothesis.20

Pieter Biesboer has put forward quite remarkable arguments in favor of his identification of the present sitter as Cornelis Adriaensz. Backer († 1655), who appears in Hals’s civic guard portrait of 1632/1633 (A2.10), standing second from the left. He points to the similarity between that sitter and the present picture’s round, bald head. Biesboer supports his thesis by quoting from a reference in Backer’s estate inventory of 1656: ‘two portraits of lord burgomaster Backer and his wife’.21 Backer had married in December 1630 and was one of Haarlem’s burgomasters in 1633 and 1637-1638. He rose to the rank of colonel in the Calivermen civic guard and became a representative in the States General from 1646 to 1648. The grand manner of the gentleman’s appearance in the present picture would fit in with these roles, but if we give serious consideration to the stylistic elements, they should be dated earlier than the wedding in 1630. The sitter is probably also older than the captain on the guardsmen’s picture; he is taller and more bulky than that rather short and dainty gentleman, if we take his later portrait in the painting by Pieter Soutman (1593/1601-1657) of 1642 into account [4].22 In Hals’s, as well as in Soutman’s guardsmen’s portrait, his face is less fleshy, more angular and more creased. The shape of the eyebrows differs, as does the shape of the eyes in their sockets, the cheekbones and chin – which is v-shaped there and rounder here. In both paintings Backer’s eyes are dark brown; the present sitter appears to have a lighter, green-grey eye color. In addition, the hair, moustache and beard could not be changed at random at the time; it is not likely that a man with such thinning temples as in the Frick portrait, could return to a full head of hair a few years later, as is seen in Soutman’s depiction. The fact that Backer owned a portrait of himself and his wife is not unusual and still quite far from the possibility that Hals was the painter.

A1.41

4

detail of Pieter Soutman

Officers and sub-alterns of the Calivermen's civic guard, Haarlem, 1642

oil on canvas, 203 x 344.5 cm

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. OSI-313

A1.42 Frans Hals, Portrait of Lucas de Clercq, c. 1627-1628

Oil on canvas, 121.6 x 91.5 cm

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum (on loan from the City of Amsterdam), inv.no. SK-C 556

Pendant to A1.72A [5]

Slive commented on the restrained and austere clothing in the portraits of Lucas de Clercq († 1652) and his wife Feyntje van Steenkiste (1603/1604-1640), which was typical for the Mennonites' strict way of life.23 The sitter and his wife belonged to this protestant sect and had signed their marriage certificate in Haarlem on 11 January 1626.

In the literature, there are different opinions regarding the authorship and date on this pair of portraits. With its blond coloring, the round modelling of the head and the emphasis on solid volume in the body, the male portrait is close to the Banquet of the Officers of the Calivermen civic guard of 1627 (A2.8A). The style of the collars and clothing is also comparable. Based on these characteristics, the execution of the Portrait of Lucas de Clercq can be dated to the late 1620s. Unfortunately, no date has been preserved in the painting itself, or in related documentation. While the measurements, representation and background color of the female portrait match with those of the male counterpart, there are differences in style and quality of execution. The generous and effective style, and the vibrant appearance of the present are not visible in the female likeness, which today appears flatter and less expressive due to overpainting, and which for some reason was painted as late as 1635.24

A1.42

5

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Feyntje van Steenkiste (1603/1604-1640), dated 1635

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. SK-C-557

cat.no. A1.72A

A1.43 Frans Hals, Young woman, c. 1628

Oil on panel, 58 x 52 cm

Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv.no. MI 926

This genre-like portrait presents an uncommon subject, both in Hals's oeuvre and in his time. Even the landscape in the background is unusual, since it does not form a coherent whole with the light-dark contrasts in the woman’s face and body, which suggest she is lighted in an enclosed space. In other ways, this problem also occurs in the Heythuysen portrait and in the double portrait of the Massa couple (A2.6, A2.8).

As Slive explained, the sitter was typically recognizable as a prostitute at the time, further indicated by her loose hair and open blouse.25 Well-known representations of this type can be found in The procuress and the Smiling girl holding an obscene image [6], both by Gerard van Honthorst (1592-1656) and dated 1625.26 If my assumption is correct, that Frans Hals has seen Honthorst’s 1625 depiction of Granida and Daifilo in the latter’s workshop, he probably must have also seen these two paintings there, using them as sources of inspiration for his own work.27 A merry prostitute dressed in a similar outfit as Hals’s, is frequently depicted in the center of tavern scenes by Haarlem genre painter Jan Miense Molenaer (c. 1609/1610-1668).28

Unlike in Hals's earlier depictions of merry couples (A3.1, A3.2, A3.3), there is no sense of spirited exuberance or even of an uninhibited party mood or suggestive winking in the present painting. Rather, the woman’s lowered gaze and mischievous smile suggest a slightly evasive manner, a shyness as in an unexpected interview situation. In contrast to the lascivious and brash courtesans in pictures by the Utrecht Caravaggists, a real person emerges here, who may have felt the oddness of being painted at a time when the subjects of portraits were normally persons of high social standing, holding puritanical views. Within the range of artistic genres that were common for the period, this painting cannot be considered to be an ancestral portrait, painted for family commemoration or other forms of representation. Yet, there is neither a clear didactical purpose, for example expressing a warning against misbehavior such as in Verdonck (A1.34), or displaying laughter and other distinct emotions as examples of the transience of sensory impressions. Historically, the only reason for this painting would have been a commission. Unless it was entirely private in character, the only explanation is Slive's suggestion of a commission for a gallery of courtesans, i.e. a representation on the door of a room in a brothel.29 If this was the case, Hals may not only have painted a single portrait. The interpretation is further supported by the fact that the area of the girl’s chest was originally more covered by her blouse, which can be discerned in slanting light. This indicates an interest in making her appear more like a prostitute at a later stage.

A1.43

© 2009 RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Jean-Gilles Berizzi

6

Gerard van Honthorst

Lachende vrouw met een obscene afbeelding, 1625 gedateerd

Saint Louis (Missouri), Saint Louis Art Museum, inv./cat.nr. 63:1954

A1.44 Frans Hals, Portrait of a young man wearing a wide-brimmed hat, c. 162930

Oil on panel, 29.3 x 23.2 cm

Washington, National Gallery of Art, inv.no. 1940.1.12

Arthur Wheelock outlined the special character of this small-scale painting, which is tied to traditional portraiture by the use of a feigned oval frame and the sitter's formal pose. He referred to similar small portraits of family members in the context of Jan Miense Molenaer's (1609-1668) family picture of c. 1632.31 He also raised the possibility of a connection to the Hals family, in this instance to the son Harmen Hals (1611-1669), whose age would match with that of the sitter in the present portrait.32

The sketchy manner of execution relates this picture to genre paintings like Two laughing boys (A1.33), Verdonck (A1.34) and Laughing boy with a wine glass (A1.35). These informal elements would be an argument in favor of the picture not being a commission but rather a portrait within the family or a circle of friends.

A1.44

Notes

1 For complete references to inventories and catalogues, see: Seelig/Binzer/Dullaart 2010, p. 100.

2 According to Seelig, the two paintings are so obviously related to each other compositionally, that it seems unlikely they once could have formed a coherent series of the Five Senses, with additional paintings. He also does not necessarily see them as depictions of the sense Taste and Hearing. See: Seelig/Binzer/Dullaart 2010, p. 98-99.

3 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3 (1974), p. 35. Bredius suspected these depictions of the Five Senses to have been painted possibly by Dirck or Harmen Hals, see: RKD, Bredius notes (also for a full transcription of the inventory).

4 Inventory of Willem Schrijver, 26 October 1611, Amsterdam. See: Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 409, doc. 166.

5 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3 (1974), p. 35.

6 For instance: Laughing boy with a flute, oil on panel, 38 x 37.5 cm, in sale, Munich (Neumeister), 20 November 2013, lot 300.

7 In other works it could also be a diagonally stretched canvas, see: Young violinist (A4.2.51).

8 Hofstede de Groot 1907-1928, vol. 3 (1910), p. 9, nos. 4-7.

9 Sale The Hague (Ottho van Thol), 25-28 August 1760, lot 134 (Lugt 1109); sale The Hague (Rietmulder), 13 April 1771, lot 35 (Lugt 1917); sale Amsterdam (Jan Yver), 1-3 May 1771, lot 34 (Lugt 1926).

10 Minich 1774, nos. 1894-1897.

11 Exhibition Pushkin Museum, Moscow, 17 July to 9 September 2012.

12 Linnik 1959, p. 70-76.

13 Hendrick ter Brugghen, Series of the four evangelists, 1621, Deventer, Museum De Waag.

14 Abraham Bloemaert, St Matthew and the angel, 1621, oil on canvas, 64.8 x 54 cm, in sale London (Christie’s), 14 December 1990, lot 118.

15 ‘De vyer Evangeliste in wit en swart geschildert’, see: Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 197.

16 Sale London (Christie, Manson & Woods), 20 October 1972, lot 83.

17 Schillemans 1992, p. 45.

18 Sale London (Sotheby’s), 3 July 1997, lot 22.

19 Minich 1774, no. 1897.

20 Wheelock 1995, p. 70; Valentiner 1923, p. 109, 313.

21 ‘2 contrafeytsels vande heer burgem. Backer en zijne huysvrou’; Biesboer/Togneri 2002, p. 138-139.

22 Pieter Soutman, Officers and sub-alterns of the Calivermen's civic guard, Haarlem, 1642, oil on canvas, 203 x 344.5 cm, Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. OSI-313.

23 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 264.

24 This date can also be found on an inscription on the back of a drawing after the portrait of De Clercq from the late 18th or early 19th century (D100): Hals 1635 N 242.

25 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 1, p. 92-93.

26 Gerard van Honthorst, The procuress, 1625, oil on panel, 75.8 x 107.5 cm, Utrecht, Centraal Museum, inv.no. 10786.

27 Gerard van Honthorst, Granida and Daifilo, 1625, oil on canvas, 145.2 x 179.3 cm, Utrecht, Centraal Museum, inv.no. 5571. See chapter 1.3.

28 Jan Miense Molenaer, Merry company with a violinist in a tavern, oil on panel, 73.1 x 106.6 cm, in sale London (Sotheby’s), 8 December 2016, lot 130; Jan Miense Molenaer, Company playing cards, oil on panel, 48.5 x 68.7 cm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. SK-A-3023.

29 Slive 2014, p. 119.

30 C. 1629 on stylistic grounds and on the basis of the dendrochronological report.

31 Jan Miense Molenaer, Probable self-portrait with family, oil on panel, 62.3 x 81.3 cm, Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. OS 75-332.

32 Wheelock 1995, p. 66-68.