A1.72 - A1.80

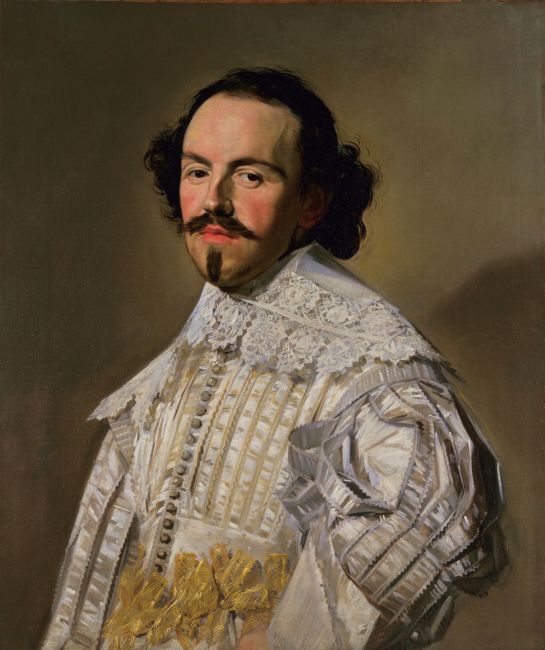

A1.72 Frans Hals, Portrait of a man, 1635

Oil on canvas 87.5 x 68.5 cm, inscribed, dated and monogrammed center right: AETAT SVAE 50/ AN° 1635 / FH

Amsterdam/Geneva, Salomon Lilian Old Master Paintings

Pendant to A3.36 [1]

Together with the Portrait of a woman (A3.36) dated 1640, the present picture 1635 appeared at auction in 1797, 1819 and 1876.1 The supposed relation between the two portraits could be correct, considering their size: the female portrait was slightly cut at the upper edge and measures 85.2 x 68.1 cm, nearly the same size as the male counterpart. The common provenance connects both pictures to the Hals workshop. The question is whether the two other portraits with feigned ovals (A1.79, A1.80), which are quite similar in size, would fit into the context of a more extensive family gallery. The catalogue of the 1819 sale states: ‘Two portraits, wherein a man set in years wearing a round hat and Spanish dress, the other an aged woman in simple house dress […] Both pictures have the signature of the master but from different years […] The man is 1635, while the woman is 1640!’.2 Slive mentioned the notable time gap, which need not necessarily exclude a designation as pendants. He assessed the Portrait of a woman as a ‘convincing original’, and the supposed pendant as ‘too feeble to ascribe to Hals’.3 Today, the situation can be regarded as reversed.

Martin Bijl’s restoration of the male portrait in 2019 made Hals’s brushwork visible again all areas; the face, the collar, the hands and the black suit. Their cool accentuated tonality now emerges – in contrast to the earlier, yellowed and smoother surface impression. To achieve this, an entire layer of smoothing overpainting needed to be removed.

1.72

© Salomon Lilian / Photo: René Gerritsen

1

Frans Hals (I) and workshop

Portrait of a woman, 1640

oil paint, canvas, 85.2 x 68.1 cm

center left: AETAT SVAE 53 /AN° 1640

Ghent, Musée des Beaux-Arts, inv.no. 1898-B

Photo: Hugo Maertens

cat.no. A3.36

2

Frans Hals (I)

Portret van Lucas de Clercq (....-1652), ca. 1627-1628

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. SK-C-556

cat.no. A1.42

A1.72A

A1.72A Frans Hals, Portrait of Feyntje van Steenkiste, 1635

oil on canvas, 121.9 x 91.5 cm, inscribed and dated upper left: AETAT SVAE 31/ AN° 1635

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. SK-C-577

Pendant to A1.42 [2]

This portrait depicts Feyntje van Steenkiste (1603/1604-1640), who had married Lucas de Clercq (†1652) in 1626. The identification is confirmed by the painting’s provenance which leads back to the De Clercq family, as well as by the matching life dates of the sitters. The 17th-century treatment of the reverse of the canvas, its format and the composition clearly confirm the picture as the pendant of the portrait of the sitter’s husband as well (A1.42). However, in its current condition it lacks the male portrait’s physical presence and the immediacy of expression, because the rendering of the facial features appears rather flat. Besides the plasticity and vitality of the man’s likeness, which almost jumps out of the picture, the female portrait seems rigid. The Portrait of Feyntje van Steenkiste is dated 1635 and as such it is of a later date than its counterpart, which stylistically fits in the mid-1620s. It remains unknown why the female portrait – which was clearly matched in size to the male portrait – was created nine years later. In any case, also the structure of the canvas and the ground layer are different, which normally would not be the case with simultaneous commissions of portrait pendants. On the basis of scientific examination of the paint layers, Hendriks and Levy-van Halm describe the differences between the two pendants: ‘Examination techniques of X-radiography, infrared reflectography and paint sampling, confirm a difference in their canvas supports and in the initial paint layers applied. However, final paint application and especially the contours show a close similarity. Possibly the pendants were begun by different hands and brought to completion by one hand, in order to unify them. A comparable practice would be the studio of Rubens, where finishing touches were added by the master’.4 Further examinations conducted at the J. Paul Getty Museum in 2007 and 2008 confirm the differences in the density of the canvas – finely woven canvas in the present picture as opposed to a coarser weave in the pendant – and a different ground layer – there is vermillion as a red admixture in the colored ground in the present painting, opposed to red earth in the ground of De Clercq’s portrait. The robust drawing of the facial features is clearly recognizable: the lines of the eyelids, the pupils, the line of the mouth and the shadow of the nose are contoured in well-defined brushstrokes. A few lines also mark the thin brows and the shades under the cheekbones. Likewise, the dark shadows and highlights in the fingers and the folds of the dress are equally marked, as is the knob on the chair with the lion’s head, modelled with a few accents.

On the basis of the similarly flat rendering in the self portrait of Judith Leyster (1609-1660) from c. 1630,5 I suspected in 1989 that she, who frequently imitated Hals’s style, was the creator of the portrait of Feyntje van Steenkiste.6 Nevertheless, the currently available detail-images of both paintings do not support this hypothesis. Zooming in into the Leyster self-portrait shows how different the manner of painting is from Hals’s. And detailed examination of the portrait of Van Steenkiste surprises by revealing Hals’s characteristic execution in the hands and costume.[3][4] If we more thoroughly examine the manner of representation of her dress, we discover delicate paint layers in black-grey tones, with securely inserted black contours. The particularly well preserved Portrait of a woman, dated 1637 (A1.85) offers itself as a comparative painting from the same period of origin. Similar as in that painting, we can also recognize Frans Hals in the portrait of Feyntje van Steenkiste as an observer of the silky surface of the fabric, who interrupts delicate grey-in-grey passages with hard black contours. This is done with such a subtle grasp of nuances and at the same time with a determinate emphasis on single sharp accents, that none of Hals’s assistants could ever be held responsible for this clear and angular, yet semi-abstract representation.[7][8]

The hands, which are depicted with only a few brushstrokes, can also be attributed to Hals himself, and the same applies for the bonnet and collar. In the end, the only question that remains open, is who has painted the face, which in some parts definitely differs from Hals’s style of painting. These differences become particularly clear when juxtaposing the portrait of Feyntje van Steenkiste to other female portraits by Hals, such as the Portrait of a woman, also dated 1635 (A1.78) [5] and the portrait possibly depicting Maria Larp, which probably dates from the same period (A1.79) [6] as well. Following the manner of execution in these two portraits, it becomes clear that in the face of Feyntje van Steenkiste, there are narrow islands in which Hals’s characteristic handwriting can be identified. These are the eyes, their sockets and the eyebrows, as well as the right hand side lower eyelid, the shadow of the nose and the right hand side nostril. Of the mouth, only the line between the lips has remained. The rest has been covered in a thick, light colored paint, thus becoming flat and rigid. The lower eyelid on the left has been painted over, as is the white of the eye on the right. The modelling of the corners of the mouth and the nasolabial folds have completely disappeared. Theoretically, these parts could also be the work that was delegated to a workshop assistant. Yet the patchy application and the underlying layers of paint that shimmer through, argument for a subsequent revision instead. I am not in the position to judge whether these additions can be removed or softened, but it would be nice to regain some of the original, more animated, facial expression of the sitter.

3

Detail of: Judith Leyster

Self-portrait, c. 1630

Washington, National Gallery of Art

4

Detail of cat.no. A1.72A

5

Detail of cat.no. A1.78

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a woman, 1635

New York, The Frick Collection

© The Frick Collection

6

Detail of cat.no. A1.79

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a woman, c. 1635

London, National Gallery

7

Detail of cat.no. A1.85

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a woman, 1637

Antwerp, The Phoebus Foundation

© The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerpen

brightness increased digitally

8

Detail of cat.no. A1.72A

brightness increased digitally

A1.73 Frans Hals, Portrait of a man, c. 1635

Oil on panel, 67.5 x 57 cm

Stuttgart, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, inv.no. 2500

Pendant to A1.74

The format of this picture and its pendant is unusual. A square panel, set on edge, with its four corners cut off, forms the basis of the octagonal format. Similar to some of Hals’s genre paintings, the wood grain runs in a diagonal direction – from the upper left to the lower right in the male pendant, and in opposite direction in the female counterpart.7 This structure is visible through the thinner paint layers and in raking light, providing extra animation to the portraits.

Interestingly, this pair of pendants is the only case in Hals's oeuvre where the woman appears on the left and the man on the right. Generally, portrait tradition prescribes the opposite arrangement; with the light usually coming from the left, automatically creating smoother facial features in the female face - which is lit more from the front – and a more angular emphasis on the male face which is lit from the side. Slive presumed a particular form of commission as the reason for this divergence; according to this, the husband would have been portrayed on his own before marriage and the wife's portrait would have been added later in a fashion to match the existing portrait.8 There could also have been other reasons, even a physical defect that would have demanded viewing the man from the left, respectively the woman from the right.

A1.74

A1.73

A1.74 Frans Hals, Portrait of a woman, c. 1635

Oil on panel, 67.5 x 57 cm

Stuttgart, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, inv.no. 2499

Pendant to A1.73

Hals seems to have dealt with the lighting difficulty by moderating the facial shadows in the woman’s face, in contrast to the sharper shadows in the male face. In addition, used a darker background color, in order to make the woman’s face appear lighter. Both faces are executed with distinct details and very smooth modelling in flowing brushstrokes, different from the angular accents from the portraits from 1633 (A1.56, A1.57, A1.58), and already approaching the dated works of 1635. Both pictures display this stylistic tendency.

A1.75 Frans Hals, Portrait of a man in white, c. 1635

Oil on canvas, 68.7 x 59.1 cm

San Francisco, Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, inv.no. 75.2.5

Valentiner compared this elegant portrait to the 1624 Laughing cavalier in the Wallace Collection (A1.16).9 Indeed, the posture is similar, but the temperament on display is entirely different: the present ‘Adonis’ cannot hide a sour and skeptical attitude. He is turned towards the light which comes from the left, typically the position of a female sitter in a pair of pendants. Hals's painterly bravura is evident in the delicate nuances of yellow, white and ivory of the bows, the silk of the doublet and the lace collar. The somewhat shyly turned head above is built up with strong flesh tones. Hals's psychological characterization could be based on the sitter's displeasure with the boring task of modelling. The reality of a painful posing, and possibly the underlying snobbery in the gaze on the painter opposite cannot be bettered. Overall, the paint surface is well preserved, there is only a slightly irritating filling on the shaded side of the nose bridge.

A1.75

A1.76 Frans Hals, Head of a girl,10 c. 1635

Oil on panel, ø 31 cm, monogrammed right: FH11

Paris, private collection

This face of a child was modelled so loosely and with such few brushstrokes that it can only have been painted by Frans Hals himself. It has not been listed in previous literature. The area to the right of the face was recognizably overpainted. The light background covers the original wide hair area, with merely some thin locks placed on top.

Recently, Marieke de Winkel drew attention to the clothing of the depicted child, identifying it as characteristic female dress: "... it is definitely a girl because she is wearing a rijglijf. The red shoulder straps over the shirt are a sure sign of that. According to estate inventories, rijglijven were always red (sometimes pink) and were only worn by girl and women and always over the shirt. The whole rijglijf looks like the one in the Kitchen scene with the parable of the rich man and poor Lazarus, attributed to Pieter de Rijck in the Rijksmuseum[9]. The combination of a skirt and rijglijf (in English: stays, or a pair of bodies) over a shirt was an informal attire. All women wore it as undergarments but in portraits it is usually covered by outerwear. In genre paintings, we come accross it often and there it is worn by working woman, who literally had to roll up their sleeves".12

A1.76

9

attributed to Pieter Cornelisz. van Rijck or Anonymous Northern Netherlands (hist. region) c. 1610-1620

Kitchen interior with the parable of the rich man and poor Lazarus, c. 1610-1620

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. SK-A-868

A1.77 Frans Hals, Portrait of a woman, c. 1635

Oil on canvas, 76 x 61.4 cm

Berlin, Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie, inv.no. 801

In its confident modelling of the facial features with similar strong accents in the shadows, this elegant portrait seems closest to the 1635 Portrait of a woman (A1.78), and can thus be dated c. 1635 as well. The painting was acquired by the Berlin Gemäldegalerie in 1841, and was for a long time considered to be the pendant to the Portrait of a man (A3.18), acquired a year earlier and made to match in size by additions to the canvas. However, the man is depicted from closer-by, and the soft and fluid style of painting in the female portrait differs from the angularly rendered features of the male portrait.

In 2019, the team of Anna Tummers and Arie Wallert published the results of a joint research project into the technique and materials of Hals, with the present painting as its subject. Using five non-invasive investigation techniques, the canvas, ground and paint layer were analyzed. Interesting is the documentation of the various dimensions of the painting’s stretching: by 1767 – probably its original size – it was larger at the top, bottom and left hand side than it is today. It was reduced by 1786, and then again slightly enlarged on the lower and left edges, resulting in the currently visible picture plane. In their conclusion, the authors list the most striking results of their research into Hals’s choice of colors and pigments, and his technique, such as the ‘very sparse and loose initial sketch, efficient use of the ground color (using translucent glazes over the ground to create shadowy skin tones and brown hair) and speed of application of the paint’. Analysis of the pigments revealed a ‘very distinctive use of blue azurite to create various types of grey shadows [...]’. The researchers also found that Hals used different mixtures of pigments for passages that are seemingly the same color. Finally, the study demonstrates that Hals had in this instance used a pre-primed canvas, the format of which he indicated by incising a line into the ground layer, functioning as a border.13

A1.77

Photo: Christoph Schmidt; Public Domain Mark 1.0

A1.78 Frans Hals, Portrait of a woman, 1635

Oil on canvas, 116.5 x 93.3 cm, inscribed and dated upper left: AETAT SVAE 56 / AN° 1635

New York, The Frick Collection, inv.no. 1910.1.72

Hals used this sitter’s self-righteous pose on several occasions, with one hand on the chest and the other holding a devout book between the fingers. Squeezed into her expensive conservative silk outfit and tied in by the conventional portrait representation, she nevertheless glances at the viewer in a very lively manner. The modelling of this kindly bulldog-like face is a bravura masterpiece by the artist [10]. The spatial suggestion of a background wall with a lighter projecting part is notable. It has a parallel in the Portrait of Cornelia Claesdr. Vooght of 1631 (A3.20), but the present picture has a lighter and more diffuse background, against which the compact appearance of the sitter in the armchair stands out distinctly. The canvas was trimmed on all sides.

A1.78

© The Frick Collection

10

Detail of cat.no. A1.78

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a woman, 1635

New York, The Frick Collection

© The Frick Collection

A1.79 Frans Hals, Portrait of Marie Larp, c. 1635

Oil on canvas, 83.4 x 68.1 cm

London, National Gallery, inv.no. NG6413

Probably pendant to A1.80

The identification of the sitter is based on a label on the stretcher with the note: ‘Mademoiselle Marie Larp fille / de Nicolas Larp et de / Mademoiselle *** de / Wanemburg’.14 In the auction of paintings from the collection of Comte Eugène d’Oultremont in 1889, this picture was listed as ‘Maria Larp’, together with the portrait of ‘Pieter Tjarck’, that has the same format but a slightly differing oval frame. In 1972, I had assumed a connection of the present picture with the Portrait of a man (A4.3.6), based on Valentiner's erroneously listed size.15 As the larger size of the latter is now known, there is no longer any reason for the assumption. The identification of the sitter as Marie Larp († 1675) has a historical background, as outlined by Slive, in accordance with information held by the Haarlem archives. According to these, one Maria Claesdr. married one Pieter Dircksz. in Haarlem in 1634. With her full name as Maritgen Claesdr. Larp, this Marie reappears in 1646 as the widow of Pieter Dircksz. Tjarck.16 It seems thus likely that the two pictures are companion pieces, even though the male portrait is rougher and more angular than the female one, and may have been executed a little later.

A1.80

A1.79

A1.80 Frans Hals, Portrait of Pieter Dircksz. Tjarck, c. 1636-1637

Oil on canvas, 82.3 x 69.9 cm

Los Angeles, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, inv.no. M.74.31

Probably pendant to A1.79

The elegant sitter holds a rose in his right hand, which could be read as a symbol of love for his wife but perhaps also of human transience. The oval frame is strangely irregular in shape, as if bulging on the lower left. It is not clear if this shape is original. The modelling of face and hands differs from that of the presumed pendant, and is closer to portraits dated 1637.

A1.80a Anonymous, Portrait of Pieter Dircksz. Tjarck

Oil on canvas, 101 x 81 cm

Liège, Musée des Beaux-Arts, inv.no. 646

Enlarged copy after the bust-length Portrait of Pieter Dircksz. Tjarck, featuring the sitter standing in three-quarter length.

A1.80a

Notes

1 Sale Amsterdam (Schley), 21-22 June 1797, lot 90 (Lugt 5624); sale Leipzig (Lampe), 17-20 May 1819, lot 35; sale Paris (Pillet), 16 March 1876, lot 21 (Lugt 36278).

2 'Zwey Portraits, wovon das eine einen Mann von gesetzten Jahren im runden Hut und spanischer Kleidung, das andere eine bejahrte Frau in einfacher Haustracht darstellt’ […] Beyde Bilder haben die Signatur des Meisters aber verschiedene Jahrezahlen […] Das Mänliche ist 1635, das weibliche hingegen 1640 gefertigt!’. Transcription from Trautscholdt 1957, p. 229.

3 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3 (1974), p. 72.

4 Hendriks/Levy-van Halm/Van Asperen de Boer 1991, p. 52.

5 Judith Leyster, Self-portrait, c. 1630, oil on canvas, 74.6 x 65.1 cm, Washington (D.C.), National Gallery of Art, inv.no. 1949.6.1.

6 Grimm 1989, p. 238-239.

7 Such as cat.nos. A1.36, A1.81, A3.4 and A3.31.

8 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 56.

9 Valentiner 1923, p. 313.

10 The title of the painting was changed from Head of a boy to Head of a girl in May 2025, in reaction to an e-mail of Marieke de Winkel to the author.

11 Narrow and in unusually thin lines.

12 E-mail Marieke de Winkel to the author, April 2025.

13 Tummers et al. 2019, p. 937-938, 941.

14 Transcription from Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 61.

15 Grimm 1972, p. 202, no. 75; Valentiner 1923, p. 149.

16 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 60, 61.