A1.81 – A1.90

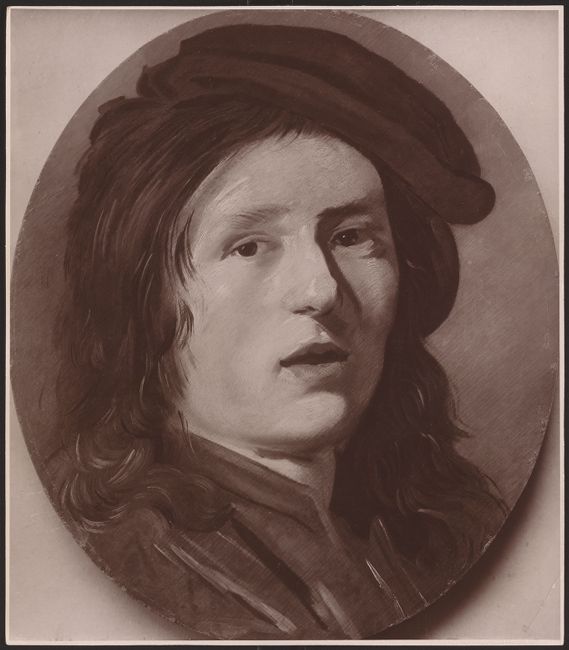

A1.81 Frans Hals, Boy pointing with his finger, wearing a beret, c. 1636-1637

Oil on panel, 41.5 x 39 cm

London, Sphinx Fine Art, 2014

This painting was sadly cut in size, but continues Hals’s sequence of moralizing genre paintings in the form of busts and half-length figures. The gesture of the raised finger is didactic in character and recurs several times in Hals’s oeuvre (A3.1). In this instance it probably refers to the transience of youth and beauty. With his full hair, actor’s beret and cloak thrown over, this representation of a young man is not actually a portrait. It shows him as giving a stage performance, comparable to the half-length figures in The merry lute player (A1.26) and Young man holding a skull (A1.29). Hals follows the model of the Utrecht school, such as is visible in the Young man wearing a burgundy jacket and beret by Jan van Bijlert (c. 1597/98-1671).1

Today’s appearance of the present picture – originally diamond shaped – was recovered in the course of several restorations and examinations since 1981. Before, the collar had been changed and the hand had become invisible through overpainting. A copy of the overpainted state was formerly in the Epstein collection in Baltimore and later with Newhouse Galleries in New York, which Valentiner thought to be probably a portrait of one of Frans Hals’s sons (A1.81a).2 From today’s perspective, it is certainly possible that one of Hals’s sons sat for such a genre painting, yet any other easily available model would have done just as well.

A1.81

A1.81a Anonymous, Boy wearing a beret

Oil on panel, 38 x 32.4 cm

New York, Newhouse Galleries, by 1937

This anonymous copy shows the composition of Boy pointing with his finger, wearing a beret in the overpainted condition.

A1.81a

A1.82 Frans Hals, Portrait of Nicolaes Pietersz. Duyst van Voorhout, c. 1636-1637

Oil on canvas, 80.6 x 66 cm

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv.no. 49.7.33

With his arm out akimbo in a powerful posture and heavy in body weight, the sitter appears similar to the portraits of the Laughing cavalier (A1.16) or of the prosperous merchant Willem van Heythuysen (1585-1650) (A2.6) from a decade earlier. In the present picture, the expensively dressed gentleman is moved even closer towards the viewer. We can imagine Frans Hals sitting at his easel, looking up at his sitter as he is huffed and puffed at.

The painting used to hang in Petworth House. According to the catalogues of the collection there dating from 1856 to 1920, the sitter is Nicolaes Pietersz. Duyst van Voorhout (c. 1600-1650), owner of the Swan’s Neck brewery. This information was based on an inscription on the reverse that is no longer preserved. Duyst van Voorhout was a brewer, born in 1599 or 1600 which makes him about 36 to 37 years old at the time when he was painted. He was a bachelor and apparently vain, as his expensive outfit suggests. In his estate there were 47 paintings, including a work by Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) and one by Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617). His estate inventory lists nine portraits without naming the painters.3 This disregard is typical for the contemporary approach to this genre, probably including Frans Hals’s role as portrait painter - and not just by this patron.

A1.82

A1.83 Frans Hals, Portrait of a man, possibly Jan Hendricksz. Soop, 1637

Oil on canvas 82 x 66 cm, inscribed, dated and monogrammed center right: AETAT. 52/ A° 1637 FH

São Paulo, Museu de Arte de São Paulo, inv.no. MASP.00187

Overall, the paint surface has suffered severely from infilling and flattening during lining. Slive noted these losses, which are particularly apparent in comparison with the engraving by Pieter de Mare (1758-1796) (C28). Details like the half of the left ear, clearly discernible in the engraving, were eliminated through later retouchings. Slive also pointed out that the inscription was reworked twice. He mentioned the unclear age of the sitter, where the second digit could be read as ‘2’, but probably was reworked.4 He also argued in favor of reading the date as ‘1631’, while the majority of other authors opted for interpreting the last digit as ‘7’, thus assuming a date of completion in 1637. In my view, a date of 1631 does not fit in with the sculptural and smoother manner of representation we observe in secure portraits from the early 1630s. I would like to outline this in greater detail in the following.

Frans Hals painted three portraits of seated officers, whose right arm is stretched towards the viewer, with the hand holding the knob of the baton. This position is displayed frontally in the left hand foreground of Meeting of the officers and sergeants of the Calivermen civic guard of 1632/1633 (A2.10) [1]. With a slight sideways turn of the body, it appears in the Portrait of Pieter van den Broecke of 1633 (A1.58) and similarly dashing is the slightly older officer in the present picture. He wears a fine lace collar and expensively embroidered doublet, but conveys his military function through his hat which resists wind and weather, and his gorget. The change in observation becomes clear in the different levels of attention given to the element of movement. The present picture no longer displays the accentuated sculptural shapes and the emphasis on spatial movement of the two earlier examples. It is distinctly softer, reinterpreted as a sequence of color lines within a painterly harmony of color fields. Individual areas such as the volumes of the face and hands, which had still been modelled with strong contrasts in 1633, are now transformed into transitions of areas of color and light. These are closer to the two guardsmen on the right hand edge of Hals’s 1639 Officers and sergeants of the St George civic guard (A2.12) than to anything else [2]. There are few other examples where Hals’s stylistic development as a change in perception, from the objective to the subjective, from draughtsman to painter, are demonstrated so clearly. Since this is an irreversible mental process, which lays out a subconscious foundation for the creative process, it would not be an arbitrary choice of expression. I therefore maintain the later date of 1637 for the present picture.

Grijzenhout and Dudok van Heel presented a series of arguments in favor of the identification of the present portrait’s sitter as the Amsterdam citizen Jan Hendricksz. Soop (1578-1638).5 Originally, he had been a glass blower, and after the closure of his glass manufacture in 1622, Het Glashuis in Amsterdam, he commanded a company of Waardgelders in The Hague. These were mercenaries who would protect the city against riots or attacks, if the civic guard were no longer in a position to manage the situation. Based on the date of completion of the painting of 1637, Soop would have been 59 years old in his portrait, which matches the present painted representation indeed. Shortly before his death, or even in anticipation of nearing the end of his life, he could have donned the outfit of his former authority accordingly and have his portrait painted in a commanding pose. The impression given by the present pictures would be in keeping with that.

A1.83

Photo: Google

1

Detail of cat.no. A2.10

Frans Hals (I), his workshop and Pieter de Molijn

Meeting of the officers and sergeants of the Calivermen civic guard, c. 1632-1633

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

2

Detail of cat.no. A2.12

Frans Hals (I) and workshop

Officers and sergeants of the St George civic guard, 1639

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

A1.84 Frans Hals, Portrait of a man, 1637

Oil on canvas, 93 x 68.5 cm, inscribed and dated upper right: AETAT. SVAE 37~/ AN° 1637

Antwerp, The Phoebus Foundation

Pendant to A1.85

This gentleman’s portrait seems to transform the formal gesture of the hands into an expression of courtesy towards the viewer. The amicable face is turned to the viewer from a lateral body posture, giving his full attention to the viewer. Few other portraits express so much graciousness. In comparison with the earlier representative portraits of men of rank, the movement is reduced and just subtle here. The painterly execution displays a reduced coloring and striking smoothness.

A1.84

© The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerpen

A1.85

© The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerpen

A1.85 Frans Hals, Portrait of a woman, 1637

Oil on canvas, 93 x 68.5 cm, inscribed and dated upper left: AETAT SVAE 36 /AN° 1637

Antwerp, The Phoebus Foundation

Pendant to A1.84

The accommodating posture of the elegant gentleman meets with the present woman’s calm and self-centered attitude. Probably in order to lift the two faces to approximately the same height, her shoulders are placed distinctly higher. The near-frontal body position and the darkening of the grey half-tones that can be observed in many portraits from this period make the figure appear somewhat solid. Under bright lighting, however, we can appreciate the masterly play of grey shades and highlighted edges that structures the dark costume in a perfectly observed, and at the same time appealing, abstract manner [3]. The modelling of hand and glove is equally simple and confident as in the male pendant. Overall, Hals’s sober physiognomic capture is nevertheless more suited to the disposition of the gentleman than to that of the lady, who is not much flattered.

3

Detail of cat.no. A1.85

© The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerpen

A1.86 Frans Hals, Portrait of a man, c. 1637-1638

Oil on canvas, 121 x 90 cm

Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, inv.no. 1276

The man’s distinctive head, with a good-natured smile and the emphasis on laughter lines next to his eyes, appears wedged in by the upturned collar. The head is depicted as if in the moment of turning, while the cheerful eyes are already directed towards the viewer. The modest gesture of the hand on the chest is relaxed. Slive accurately identified the symptoms of arthritis in this hand, which can also be observed in the Portrait of a woman of 1633 (A1.57). The man’s other hand rests loosely on the hip and belies the potential aggressiveness of such a posture. The modelling of the face and the body emphasizes the angularity and cartilaginous character of the details, in contrast to the massive compactness of the above-mentioned representations. This shift in focus moves this portrait away from the 1635 Portrait of a woman in the Frick Collection (A1.78) that Valentiner suggested as a possible companion piece.6 What seemed conceivable in the grey reproductions from earlier periods cannot be upheld on the basis of today’s color reproductions. An attempt to identify the sitter as the Friesland lawyer Johannes Saeckma (1572-1636) is now disproved as well.7

A1.86

A1.87 Frans Hals, Portrait of Jean de la Chambre, 1638

Oil on panel, 20.6 x 16.8 cm, inscribed and dated upper left: 1638./ aet 33.

London, National Gallery, inv.no. NG6411

Jean de la Chambre (1605-1668) was rector of the French school in Haarlem and devoted himself to calligraphy. Hals painted his portrait in 1638 in a small format, apparently as a template for an engraving that was created in the same year [4]. The print served as a frontispiece for a book that De la Chambre published, featuring samples of his calligraphic skill.8 Slive pointed out that calligraphers are never portrayed in reverse in engravings, because the depiction of the right hand forms a central part of the sitter’s identity.9 The portrait print of the notary and historian Pieter Christiaensz. Bor (1559-1635) (C26) also fits into this context, as he too is depicted with a quill in his hand. In the painting, De la Chambre’s hand is only outlined and hardly detailed, but his face is loosely drawn with a few confident brushstrokes and characterized as ‘speaking’ with the slightly open mouth and the raised eyebrows.

Together with the Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius (A4.1.1A), this modello for an engraving – executed as a miniature portrait in the same size and entirely by the master’s own hand – stands out in the overall production of Frans Hals and his workshop. Did the calligrapher perhaps recognize a special quality in Hals’s confident brushstroke? For Hals, a portrait was painted according to the commission, by himself or by others. In this instance, the objective was probably both the painted and the engraved image, meant to reflect favorably the abilities of the penman.

A1.87

4

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of Jean de la Chambre, after 1638

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-60.744

cat.no. C31

A1.88 Frans Hals, Portrait of a woman, 1638

Oil on canvas, 66.5 x 52.3 cm, inscribed and dated upper left: AETAT . SVAE . 41/AN° . 1638 .

Cleveland, The Cleveland Museum of Art, inv.no. 48.137

While this portrait is formal in posture and gesture, its execution is masterly and the coloring is brightened by the yellow and red accents on the bodice and the purse. The woman’s alert expression with the pursed lips is particularly memorable. The portrait is probably related to a pendant that could not be identified so far. Recently, Marieke de Winkel suggested an identification of the woman as Aeltje Dircksdr. Pater (1597-1678), which would fit in with the dates inscribed on the painting.10 However, the facial features do not sufficiently resemble those of Pater’s securely identified portrait by Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck (1600/1603-1662), dated 1653.11 In that portrait, the forehead is higher, the chin wider, while the eyebrows are more pointy. Also, the present portrait displays a rounder head. In addition, size and technique do not correspond to what is listed by Hofstede de Groot. Under nos. 240 and 241, he records a pair of pictures sold at auction in Amsterdam in 1850 and 1851, depicting Jan de Wael (1594-1663) and his wife Aeltgen Dircksdr. Pater, both measuring 73 x 54 cm, painted on panel.12

De Winkel associated the hitherto unidentified Portrait of a man (A1.101) as the companion piece of the present portrait. However, when Verspronck’s 1653 Portrait of Johan de Wael appeared – most recently with Agnew’s in London – it became clear that the men’s likenesses do not correspond.13

A1.88

A1.89 Frans Hals, Portrait of a man, 1638

Oil on canvas, 89 x 69.8 cm, inscribed and dated upper right: AETAT SVAE 38/ AN° 1638

Stockholm, Swedish Royal Collection, inv.no. 376

Pendant to A1.90

The sitter is represented in an official posture and with an affirmative gesture. He turns to the viewer with a smile that is almost apologetic and somewhat wistful. The corners of his mouth are slightly extended and his eyebrows raised. The coloring is muted and entirely focused on the face. In a subtle lighting, the much emphasized plasticity of previous years has been reduced. In its pose, lighting and psychological approach the present picture strongly resembles the Portrait of a man in Frankfurt, equally in an oval shape (A1.91).

A1.89

A1.90

A1.90 Frans Hals, Portrait of a woman, 1638

Oil on canvas, 89.1 x 70.2 cm, inscribed and dated upper left: AETAT SVAE 41/ AN° 1638

Stockholm, Swedish Royal Collection, inv.no. 376

Pendant to A1.89

As is so often the case with Hals’s female portraits, the expensively dressed sitter makes a reserved appearance, with her eyes turned to the viewer in a meaningful manner, and the lips firmly closed.

Notes

1 Jan van Bijlert, Young man wearing a burgundy jacket and beret, oil on panel, 55.3 x 45.2 cm, Amsterdam/London, Gebr. Douwes, by 2008.

2 Valentiner 1935, no. 18.

3 See Liedtke 2007, vol. 1, p. 285.

4 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3 (1974), p. 51.

5 Grijzenhout 2015, p. 14-29; Dudok van Heel 2017, p. 30-33.

6 Valentiner 1923, p. 136-137.

7 Engels 1991, p. 53-70; Ekkart 1992, p. 143-150.

8 Verscheyden geschriften, geschreven ende int koper gesneden,/ door Jean de la Chambre, liefhebber ende beminder der/ pennen, tot Haarlem. Anno 1638.

9 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 273.

10 De Winkel 2012, p. 147-150.

11 Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck, Portrait of Aeltje Dircksdr. Pater, 1653, oil on canvas, 87 x 68 cm, Berlin, Gemäldegalerie der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, inv.no. 877 A.

12 Hofstede de Groot 1907-1928, vol. 3 (1910), p. 71.

13 Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck, Portrait of Johan de Wael, dated 1653, oil on canvas, 88.9 x 69 cm, whereabouts unknown.