A2.8A - A2.12

A2.8A Frans Hals and Pieter de Molijn, Banquet of the officers of the Calivermen civic guard, 16271

Oil on canvas, 183 x 266.5 cm, monogrammed lower left: FHF

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. OS I-111

This painting is the only one among Hals’s six civic guard portraits which bears a signature – or at least where the signature has been preserved. While the probably slightly earlier Banquet of the officers of the St George civic guard (A1.30) depicts a variation of very realistic interactions between several loose groups of speakers and listeners, the present painting presents a more distinctly coherent visual pattern. Liedtke brought to mind a largely disregarded particularity of Hals’s compositions, whose rising and falling diagonals link the different elements of the pictorial scene together, following the example of Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) and other Flemish painters.2 In this case, there is no unifying activity in Hals’s portrait ensemble – the captain cutting the roast in the center is just one individual action among several others. The colonel sitting on the left is certainly the main figure, whose head is set off effectively against the dark surfaces of the clothes and the light pattern of collars and sashes behind him, yet he only commands part of the attention. In the upper half of the composition, Hals has used the black hats to emphasize the faces. This ensures a sufficient focus of attention in this area, both on the individual and on their distinctively presented facial features.

As early as 1628 the picture is referred to in Samuel Ampzing’s (1590-1632) book Beschryvinge ende lof der stad Haerlem: ‘[…] a large painting by Frans Hals of some of the officers of the civic guard in the Oude Doelen or Calivermen’s Hall, done most boldly from life’.3

On the basis of the identification sheet by Wybrand Hendriks (1744-1831), the sitters can be identified as:

1. Willem Claesz. Vooght (1572-c. 1630), colonel

2. Johan Damius (c. 1570-1648), fiscal

3. Willem Warmont (1583/1584-1650), captain

4. Johan Schatter (c. 1594-c. 1673), captain

5. Gilles Claesz. de Wildt (1576-1630), captain

6. Nicolaes van Napels (1598-1630), lieutenant

7. Outgert Akersloot (1576-1636), lieutenant

8. Matthijs Haeswindius (c. 1588-c. 1631), lieutenant

9. Adriaen Matham (c. 1599-1660), ensign

10. Loth Schout (1600-1655), ensign

11. Pieter Ramp (c. 1592-c. 1660), ensign

12. Willem Ruychaver († 1634), servant [1]

In this group portrait, the execution of the faces and hands is more consistent than in Banquet of the officers of the St George civic guard (A1.30). Lighting and coloring are closely coherent in all details, and a planar clarity links all areas of the composition together. Accordingly, Hals’s brushwork can be similarly identified in almost all the heads – with the exception of Pieter Ramp (11) and Willem Ruychaver (12). As in the group portrait of the guardsmen of St. George’s, Hals seems not to have intervened in the somewhat feeble transfer of the features of the servant [2]. In consequence, one can clearly determine the mechanical rendering of the details in this intermediate stage, especially in the collar, which was most likely the basis of the other areas. The somewhat patchily applied face of ensign Ramp also remained hardly revised [3]. It lends itself to a comparison with the clearly executed facial area of captain Warmont (3). Hals’s brushwork can only be identified in the latter [4].

The ensign on the left is noteworthy: it is Adriaen Matham (c. 1599-1660), son and pupil of the copper engraver Jacob Matham (1571-1631), who had created the engraving after Hals’s portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius (1572-1653) in 1618 (C3). Adriaen Matham’s date of birth can only be deducted indirectly from a document of 6 December 1634, in which he stated being 35 years old.4 He would thus have been born in 1599. In 1622, Matham returned from Paris to Haarlem and served as an ensign in the Calivermen civic guard from 1624 to 1627. He may have been involved in arranging the commission for Hals’s present group portrait. Later, he was to execute engravings after three important portraits by Hals: that of Pieter van den Broecke (1585-1640) (C24), Pieter Christiansz. Bor (1559-1635) (C26) and Isaac Abrahamsz. Massa (1586-1643) (C27). He was personally close to Hals, which is proven by the fact that he became the godfather of Hals’s daughter Susanna at her baptism in 1634.5 Additionally, Matham was a member of the Dutch delegation to the king of Morocco in 1640-1641. His drawing and engraving of El Badi Palace in Marrakech are unique historical documents of its magnificent appearance before its destruction a few decades later.6

The window in the background of Banquet of the officers of the Calivermen civic guard scene is glazed. The two wings each contain a round pane in the center depicting armored fighters. To the outer sides, there are rows of – probably local – coats of arms. Visible through the window is a group of trees with clusters of finger-shaped leaves, rendered in a style that can be related to Pieter de Molijn's (1595-1661) contemporaneous tree backdrops. It is obvious to assume him as the painter of this part [5].

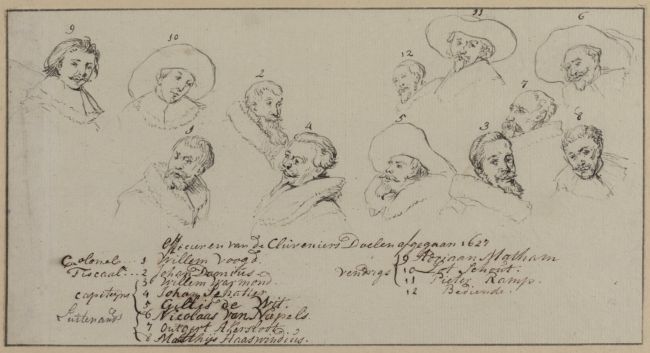

A2.8A

1

Wybrand Hendriks

Identification sheet of Banquet of the officers of the Calivermen civic guard

Haarlem, Teylers Museum, inv./cat.nr. W 043a

cat.no. D12

2

Detail of cat.no. A2.8A, head of the servant Willem Ruychaver

3

Detail of cat.no. A2.8A, head of Pieter Ramp

4

Detail of cat.no. A2.8A, head of Willem Warmont

5

Detail of cat.no. A2.8A

A2.9 Frans Hals and Claes van Heussen, Young woman selling fruit and vegetables, 1630

Oil on canvas, 157 x 200 cm, signed and dated upper right: CVHeussen fecit A° 1630

England, private collection

Considering the loose execution of the face and the stripy brushwork, the depiction of this young fruit- and vegetable seller in this otherwise smoothly-painted picture of a wide fruit stand is recognizably a contribution by a particular hand: that of Frans Hals. However, the signature indicates only the Haarlem still life specialist Claes van Heussen (c. 1598/1599 – 1630/1633) as the author of this painting. Hals’s involvement was obviously not worth mentioning separately.

The painting was first published in 1910 by Hofstede de Groot as a work by Hals, referring to the Amsterdam sales of 1810 and 1817 where it had appeared. In the latter sale catalogue, it was listed as a work by Frans Hals and ‘P. Gijzen’, referring perhaps to the Flemish painter Peeter Gijsels (1621-1691), as Hofstede de Groot suggested.7

This type of large-scale fruit and vegetable still life follows a tradition established in the Southern Netherlands by artist such as Frans Snijders (1579-1657), Joannes Fijt (1611-1661) and Peeter Boel (1622-1674). It combines a representation of the splendor of nature with hints to transience. The young woman holding a set of scales in her hand brings to mind the double meaning of the fleetingness of all beauty in nature, and the necessity of weighing facts. There was most likely also a connotation of the biblical wording ‘know them by their fruits’. Such representations were generally commissions for reception- and dining rooms. They not only refer to meals, but also – in a humanistic sense – to the seasons and the ambiguity of possessions and sensual pleasure. Slive pointed at another, slightly smaller, depiction of the same subject by Hals, listed in the supplement to the sale catalogue of the collection of Daniel Mansfeld, valued at 2 guilders.8

A2.9

© Courtesy the owner. Photo: National Gallery, London

A2.10 Frans Hals, his workshop, and Pieter de Molijn, Meeting of the officers and sergeants of the Calivermen civic guard, c. 1632-1633

Oil on canvas, 207 x 337 cm

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. OS I-112

Today, the darkened background and the discolored brown trees no longer clearly show that this was an outdoor scene. The table around which the men are grouped in conversation, stands in a garden or courtyard. An adjoining park with many broad-leafed trees is visible behind a gate. In the background to the right a house is visible at some distance. All this is much better recognizable from a watercolor copy by Wybrand Hendriks (1744-1831) [6]. With the post-exposure of the photograph on the computer screen, however, the gate in the background and the little forest can be made visible again today. The detailed execution of this part can be stylistically attributed to Pieter de Molijn (1595-1661) and his workshop, who also worked on many of Hals's other paintings.9

As in the earlier civic guard portraits, the left side of the composition, where a separate group has formed around the seated colonel, is especially emphasized. The diamond-shaped field around his head, and his hand that is placed on a commander’s baton in an imperious fashion, form a visual focal point. The group on the right seems to be engaged in an independent conversation. Their center is a captain, turning towards the viewer as if by accident and conveying the idea of an unplanned moment of observation. As in the previous group portraits, collars and sashes are used to structure the composition. Yet in this instance, they are folded even wider, forming an abstract zig-zag pattern of orange and blue color fields. Out of the seventeen actual functionaries, fourteen have been depicted in the group portrait. They are:

1. Johan Claesz. van Loo († 1660), colonel

2. Johan Schatter (1594-1673), captain

3. Cornelis Adriaensz. Backer († 1655), captain

4. Andries van der Horn (1600-1677), captain

5. Jacob Pietersz. Buttinga (c. 1600-1646), lieutenant

6. Nicolaes Olycan (1599-1639), lieutenant

7. Hendrick Pot (c. 1580-1657), lieutenant

8. Jacob Hofland, ensign

9. Jacob Steyn (1606-1679), ensign

10. Dirck Verschuyl (1592-1679), sergeant

11. Balthasar Baudart († 1658), sergeant

12. Cornelis Jansz. Ham (1591-1633), sergeant

13. Hendrik van der Boom, sergeant

14. Barent Mol, sergeant [7]

The immediacy of the depicted scene, with its frontal drive towards the viewer and the division of individual movements – which is as varied as it is psychologically plausible – give this picture its unique character. Especially the left side appears as the epitome of Hals’s gift of expression. The arrangement of the colorful sashes and flags creates a close cohesion of separate details. It is all the more astonishing that Hals’s autograph brushwork can be found to a higher degree in these accessory parts than in the faces. I myself was surprised at this discovery, which I owe to the study of high resolution photographs of the painted surface, illustrated here in several details [8][9][10]. Most astounding is the observation that Hals’s personal manner is only purely to be found in one face – that of Sergeant Cornelis Jansz. Ham (12) – and five hands. Additionally, all flags, sashes, collar, cuffs, weapons and feathers, as well as most doublets and sleeves show his typical brushwork (nos. 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, and 8). The figure of captain Johan Schatter (2) is also remarkable in this respect. In His sword, sash, and plumed hat display a wealth of brilliantly executed details, yet in the relatively smooth rendering of the face there are traces of a fine outline drawing – probably transferred from a preparatory design [11].

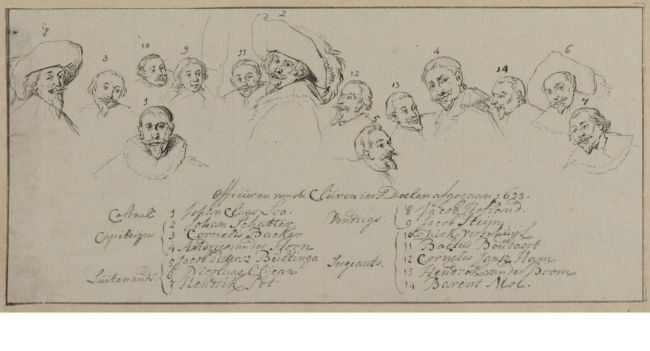

A2.10

6

Wybrand Hendriks

The meeting of officers and sub-alterns of the Cluveniersdoelen of Haarlem, c. 1780-1820

Haarlem, Teylers Museum, inv./cat.nr. W 044

cat.no. D16

7

Wybrand Hendriks

Identification sheet of The Meeting of the officers and sergeants of the Calivermen civic guard, c. 1778

Haarlem, Teylers Museum, inv./cat.nr. W 044a

cat.no. D17

8

Detail of cat.no. A2.10, the sash of Andries van der Horn

9

Detail of cat.no. A2.10, the sash of Johan Schatter

10

Detail of cat.no. A2.10, the sash of Johan Claesz. van Loo

Although thirteen of the total of fourteen faces are typical creations by Hals – in their physiognomic conception and lighting – they are executed in a softer, less accentuated manner. This suggests that Hals had created the portrait templates, which assistants copied onto the final canvas. Hals produced these designs in individual sessions with his models, presumably already on the scale required for the final execution and on convenient material such as paper or canvas. This procedure allowed him to observe the sitters in close-up and in identical lighting, without having to shift his gaze too much. Recopying of the templates was a routine task. With his subsequent corrections and amplifications of important effects, Hals was able to produce a credible overall image. The incorporation of the separate faces worked quite convincingly for Hals in this instance and in his other group portraits, in terms of size ratio as well as lighting and colors. The viewer does not realize that in a corresponding real situation the heads of the figures on the back row would have to be proportionally smaller and overall smaller in relation to the bodies. This being said, in one case this procedure of inserting separate portraits did not quite work out. The upper body and shoulders of the seated commander Van Loo – on the left – cannot be imagined here realistically, despite the optical foreshortening of his outstretched arm. This disproportion becomes particularly visible when a reproduction of this part is clarified by post-exposure on the computer screen.

What the faces executed by Hals himself look like, can be seen in many comparisons with other works. As a surprising example, however, the present picture offers the well-preserved head of Sergeant Ham (12), standing in the second row in the center of the composition. It can be assumed that this figure was added later. Little is known about the sitter; he was a pharmacist in Haarlem and also a commissioner for small claims at the court there. Hals has painted his face delicately, with a thin layer of paint. His features are drawn in a few strokes with a flat brush[12]. If one compares this observation, which concentrates on a few highlights and shadows, with the face of Commander Van Loo (1), this graphic character appears to be missing in the latter. The commander's dominating eye and nose zones have been rendered in a pulpy manner with a soft brush, which were later reinforced with thick black contours. The area of the mouth and moustache is also depicted smoothly and captured stiffly [13]. It is equally astounding to compare the face of Captain Van der Horn (4) with that of his bust portrait by Hals from 1638 (A1.93) [14][15]. When facing the detail image, one might think they are looking at a portrait from the mid-19th century. The smoothly applied paint and its saturated tonality have nothing in common with the sheer, sketch-like bravura of the later portraits. Looking back to earlier examples, the head of Captain Backer (3) lends itself for comparison with the Portrait of an elderly man in the Frick Collection (A1.41).10 Biesboer even assumed that it was the same person.11 Here too, thick impasto contrasts with the watercolor-like lightness of Hals’s autograph single portraits.

11

Detail of cat.no. A2.10, the head of Johan Schatter

12

Detail of cat.no. A2.10, head of Cornelis Jansz. Ham

13

Detail of cat.no. A2.10, head of Johan Claesz. van Loo

14

Detail of cat.no. A2.10, head of Andries van der Horn

15

Detail of cat.no. A1.93

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Andries van der Horn, 1638

canvas, oil paint, 85.8 x 67.5 cm

São Paulo, Museu de Art de São Paulo

Photo: Google

Some hand and glove sections in the present painting are also executed in a smooth manner of painting and with schematic contours. The anatomically secure depiction of hand shapes in various movements and directions here also indicates the use of preparatory studies, transferred to the final composition similarly to the sitters’ faces. By and large, we are looking at various refractions of Hals’s painting. We have a composition designed by him, into which he added some details directly, while preparing studies of other motifs. He had then inserted these by his assistants into the composition, to make further amendments while adjusting the whole image. The contributions by assistants (or by an assistant) are recognizable in the soft, less accentuated representation. An example can be found in the wax-like hand of Lieutenant Buttinga (5), which adjoins an assertively contoured cuff [16]. This latter area strikingly demonstrates Hals’s nuanced brushwork.

Finally, we find an astonishing abundance of quite typical and highly virtuoso individual contributions by the master in the other, otherwise neglected marginal areas of the composition. Thus all the costumes, the collars, the cuffs, the feather on the hats, the majority of the sashes over the men’s chests, the sash bows and –knots, and the three hanging sash ends with their lace trimming are bravura-details by Hals’s own hand. A similarly free and well-detailed painting style highlights the two flags, and hardly noticed so far is the delicate execution of the weapons, the finely cut metal surfaces of the halberds and partisans, gleaming in silver and gold above the heads of the men. When comparing this manner of execution with that in the 1639 Officers and sergeants of the St George civic guard (A2.12), one can discover Frans Hals' stupendous talent as a still-life painter, but also get a precise idea of master- and workshop-execution. Finally, Hals appears as a painter with a penchant for depicting amusing details in the figures of the two guards in the background on the right.

16

Detail of cat.no. A2.10, hand of Jacob Pietersz. Buttinga

A2.11 Frans Hals and Pieter Codde, Militia company of district XI under the command of captain Reynier Reael and lieutenant Cornelis Michielsz Blaeuw – known as The meagre company, 1633-1637

Oil on canvas, 209 x 429 cm, dated on the right: A° 1637

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, on loan from the City of Amsterdam, inv.no. SK-C-374

The exceptional, singular and only now fully appreciated honor of being both the model of one of Frans Hals’s most admired figures, and the sitter of an excellent and equally autograph portrait by Rembrandt (1606-1669), fell to Nicolaas van Bambeeck (1596-1661).12 Bambeeck was one of the wealthiest people in his district and a creditor for Hendrick Uylenburgh (c. 1587-1661), Rembrandt’s agent and influential patron. He appeared in Hals’s monumental portrait because of his temporary role as an ensign of the Arquebusiers’ civic guard company of Amsterdam’s 11th district. Unusually, its leaders captain Reynier Reael (1588-1648) and lieutenant Cornelis Michielsz. Blaeuw (1591-1638) had given the commission to paint a total of sixteen of their company’s guardsmen to a painter outside their home town – or they arranged it via the agent Uylenburgh – they chose Frans Hals from Haarlem. Dudok van Heel explained this process as follows: ‘The civic guard painting may have been commissioned in 1633 from Hendrik Uylenburgh, who subsequently engaged Frans Hals, just as in 1632 he had approached Rembrandt to execute the Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp’.13

Other than in Haarlem, the Amsterdam guardsmen had to be represented standing as full-lentgh figures. Representing sixteen figures in life-size required a substantial picture size, which Hals was to surpass only by a small margin in his group portrait of the double row of nineteen guardsmen of St George in 1639 (A2.12). Dudok van Heel assumed that Hals had not only received this commission through Uylenburgh but was also offered cheap lodgings and a suitable studio to paint his large-scale group painting.14 This was probably the former studio of the portraitist Cornelis van der Voort (1576-1624), which Hendrik Uylenburgh had rented in 1625 or early in 1626. The house with work space was located on the edge of the same quarter of Amsterdam as the homes of the sitters.

The peculiar title of the picture is based on Jan van Dijk’s (c. 1690-1769) 1758 guide of paintings in the Amsterdam town hall, whose author found all the guards in the picture so skinny that they might as well be called the ‘Meagre Company’.15 After completion, the painting was hung in the headquarters of the Amsterdam Crossbowmen’s building. Later it was moved to the Amsterdam Town Hall, where it hung in the large court martial chamber. In 1885, it came to the newly opened Rijksmuseum on loan from the city of Amsterdam, where it still remains today.

Hals had started this project in Amsterdam in 1633, and continued there in 1634, but then left it unfinished. Four documents written between 19 March and 16 June 1636 give insight into the dispute between Hals and his patrons. According to these, Hals first promised completion by June 1636, but once this date had passed, neither reminders nor threats could induce him to continue his work in Amsterdam. The documents which record Hals’s proposals for the painting’s execution are instructive with regard to his work process. They state that Hals had imposed the condition that he could paint the painting in Haarlem. ‘although he had not been obliged to do so, he had subsequently agreed to go to Amsterdam to make the initial sketches of the officers’ heads, which he would then finish in Haarlem’. According to the guardsmen, ‘it had originally been agreed that Hals would do the portrait heads in Amsterdam and fill in the detail in Haarlem for a fee of 60 guilders a head. This was later raised to 66 guilders, provided he did the work in Amsterdam instead of Haarlem, and that he completed both the heads and the full figures there, as he had already started doing in some cases’. Hals’s response states that he was ‘prepared to move the painting from Amsterdam to his house in Haarlem, where he will first finish any of the officers’ dress which has not yet been painted. He will then do the heads, and assumes that no one will object to coming to Haarlem for the purpose. However, if six or seven of the officers are not prepared to make the journey he will bring the painting to Amsterdam, where he will fill in the remaining heads’.16

A2.11

17

Schematic representation of cat.no. A2.11

The officers did not accept this proposal and it is not clear, for which reasons the process failed. It is conceivable that the patrons were negligent in attending the portrait sessions, which Hals had already complained about in the second document. This meant waiting time for him, raising the cost of his stay in Amsterdam. His initially favorable housing at Uylenburgh altered when in 1634 Rembrandt and his wife took up residence in the home of their cousin Uylenburgh. This meant Hals had to find new lodgings in Amsterdam for the duration of his commission. Dudok van Heel connects this fact to Hals’s reference to unpaid lodging costs.17 Norbert Middelkoop pointed out that Hals possibly may also have been displeased because he felt underpaid in comparison to his Amsterdam colleagues.18 It is only likely that he knew about their prices, such as the 61 guilders that Thomas de Keyser (1596-1667) received in 1632 for each of the half-length portraits in the background of the Officers and other civic guardsmen of the 3rd district of Amsterdam, under the command of Captain Allaert Cloeck and Lieutenant Lucas Jacobsz. Rotgans.19 It was often the case that portrait sessions were attended unwillingly. This was particularly true for posing in full regalia. The officers of the civic guards were members of the urban upper class of society, who were perhaps not especially accommodating towards a craftsman, albeit an esteemed portrait specialist like Hals. They were used to be deferred to, not vice versa. We also do not know whether the risk of contagion played a part during the dispute of 1636, since Haarlem was afflicted by an epidemic of the plague from October 1635 to spring 1637, to which a quarter of the population fell victim.

In the end, the Amsterdam painter Pieter Codde (1599-1678) was commissioned to finish the group portrait. Codde lived in the same 11th district as the civic guard company and was one of their members himself.20 Until then, he had specialized in genre painting in small formats. Codde managed to adapt to Hals’s painting to a surprising extent; nevertheless, his share of the painting is clearly distinguishable from Hals’s part. The figures in the right half of the composition are predominantly executed by him, as is the background. An x-ray reports some changes in the development of the scene: the posture of the guard in the center was changed, probably still by Hals himself.21 A visible building on the right was overpainted, which indicates that Hals had originally planned to set the scene outdoors.

In 1989 Martin Bijl described several stages in the development of the present picture.22 The documents about the dispute with the patrons also confirm that Hals must have met the guardsmen face to face several times. X-radiography has revealed traces of a preparatory sketch in oil which Hals used to outline the overall composition. Within this framework, he began to execute the individual figures, starting on the left. As a first step he sketched the turn and the direction of the gaze of each portrait. Hals’s confident brushstroke with its diagonal accents can be identified in all faces up to the right hand edge of the painting. Angular cast shadows on some collars are also evident. In their self-assured graduation of brightness levels they are easily distinguishable from Codde’s stiff collar contours. A separation of Hals’s and Codde’s shares in the portrait is relevant both for the historical reconstruction of the execution of this important commission and for a comparison of the two painters’ artistic approaches. The following listing records the recognizable individual contributions [17]. It must be taken into account that in the majority of the figures Hals’s share consisted of preparatory sketches and first stages of depicting the faces, while Codde’s achievements lay in the completion of the given template. His contributions were carried out carefully and delicately throughout, so that many parts of Hals’s brushwork remained present even in a half-finished state. This applies in particular to the figures in the background in the left half of the composition.

1 Captain Reynier Reael

- Hals: the bearded face, the outline of the collar and the hands

- Codde: the body, the sash, the cuffs, the rest of the collar, the chair

2 Lieutenant Cornelis Michielsz. Blaeuw

- Hals: the head; the outline of the collar, sash and hands

- Codde: the rest of the collar and the sash; the lower hand, the body

3 Nicolaas van Bambeeck

- Hals: the rough modelling of the face and beard; the costume, sash and flag

- Codde: smoothening in the flag, touches around the nose, the fine parallel hairs in the hair and beard, the lace on the chest underneath the collar, the blue bows below the orange sash

4

- Hals: the sketchy modelling of the face and mustache, the hand, the light reflections on the collar

- Codde: the rest of the collar, the costume

5

- Hals: the sketchy modelling of the face with mustache and beard

- Codde: completion of the collar, the sash

6

- Hals: the sketchy modelling of the face, beard and ear, the collar, the sash, the hands

- Codde: the hair, the halberd

7

- Hals: the sketchy modelling of the face, the collar, the hand

- Codde: the sash, and the rest of the figure

8 Carel Gerard

- Hals: the lit side of the face with the mustache and beard

- Codde: smoothening and overworking of the face and hair, the rest of the figure

9

- Hals: sketch of the face with moustache and beard, the outline of the collar

- Codde: the rest of the figure

10

- Hals: sketch of the head and the left ear

- Codde: modelling of the face, the rest of the figure

11 Pieter Ranst

- Hals: sketch of the face with the outline of the beard, the light reflections on the collar

- Codde: the beard, the hair, the rest of the collar and figure

12 Jan Pellicorne

- Hals: sketch of the face, beard and hair; most of the collar

- Codde: rest of the figure

13

- Hals: outline of the face and the collar – originally the collar was set higher - this is the figure with the fewest visible traces of Hals’s work

- Codde: completion of the face and collar, as well as the rest of the figure

14

- Hals: sketch of the bearded face, the light reflections on the collar, the outline of the arm and hand

- Codde: completion of the hair and collar, the rest of the figure

15

- Hals: sketch of the bearded face, the light reflections on the collar

- Codde: completion of the collar, the rest of the figure

16

- Hals: sketch of the face with outline of the beard and the collar

- Codde: completion of the shades on the face, hair, beard, and collar; the rest of the figure

In some instances smoothing overpaint is visible, for instance in the faces of ensign Bambeeck (3), officer Carel Gerard (8), Pieter Ranst (11) and of figures no. 7, 9 and 10 [18][19][20][21]22][23]. The portrait of Jan Pellicorne (12), on the other hand, shows the untouched brushstrokes of Hals: the beam of light running from the root of the nose to its tip has been captured in a single stroke of paint with a flat brush [24]. In contrast, the faces of figures no. 13 and 16 are uniformly executed in Codde’s somewhat fibrous manner[25][26]. Weaker parts are the posture Pieter Ranst (11), who seems to be tilting backwards, and the repetitive superimposition of the hands of figures no. 15 and 16 [27]. As tightly as the eight guardsmen in conversation on the left are grouped together, so peculiarly isolated appear their eight colleagues on the right hand side. In the latter can be recognized the separate execution in the workshop. Hals probably would have created a different set-up in this part, making use of lighting and compositional devices such as sashes and hand gestures. The six figures on the right, finally, are not fully convincing in their bodily proportions and positioning of the feet.

Time and again, the present painting has inspired reflections on the difference in style between the two contemporaneous painters. The different manners of execution of the faces, hands and costumes are obvious despite Codde's attempts in approximating Hals’ examples. Yet, both painters come very close to each other in their rendering of arms, and one can particularly appreciate Hals's gift of observation and attentiveness in this special field. As the detail-illustrations reveal Codde was also sensitive to the observation of lighting and reflection. His renderings of several rapiers, a halberd and a partisan show the evenly distributed gradations of brightness in the highlighted edges and reflection points [28][29]. In contrast, Hals rather captured the dynamic change of brightness on the respective materials, particularly brilliantly in the weapons in Gathering of the officers and sergeants of the Calivermen civic guard of 1632-1633 (A2.10) [30][31]. If one wonders whether he has not called in a specialist here, a look at the weapons and seat cushions, which are already unsurpassed in their characterisation in the early Banquet of the officers of the St George civic guard of 1616 (A2.0), will prove instructively.

18

Detail of cat.no. A2.11, head of (3) Nicolaes van Bambeeck

19

Detail of cat.no. A2.11, head of (8) Carel Gerard

20

Detail of cat.no. A2.11, head of (11) Pieter Ranst

21

Detail of cat.no. A2.11, head of figure 7

22

Detail of cat.no. A2.11, head of figure 9

23

Detail of cat.no. A2.11, head of figure 10

24

Detail of cat.no. A2.11, head of (12) Jean Pellicorne

25

Detail of cat.no. A2.11, head of figure 13

26

Detail of cat.no. A2.11, head of figure 16

27

Detail of cat.no. A2.11, hands of figures 15 and 16

28

Detail of cat.no. A2.11, halberd by Pieter Codde

29

Detail of cat.no. A2.11, rapier by Pieter Codde

30

Detail of cat.no. A2.10, halberd by Frans Hals

31

Detail of cat.no. A2.10, rapier by Frans Hals

Most recently, Middelkoop succeeded to identify some of the sitters in this group portrait. He convincingly identified the figure in the centre foreground (8) as probably being Carel Gerard (1608-1673), who is proven to be a member of the civic guard company presented here.23 A portrait by Govert Flinck (1615-1660) dated 1639 is traditionally connected with his name.24 The sitter’s striking physiognomy is recognisable in the present group portrait, despite the sharp turn of the face. Other members of the company at the time were Jean Pellicorne (1597- after 1639) – no. 12 – who was painted by Rembrandt around 1633 – recognizable by his wedge-shaped face and pronounced long nose – and the regent Pieter Ranst (1590-1641), no. 11, of whom a clearly matching portrait has survived.25

It is also conceivable that Codde, who belonged to the company at the time as well, appears in the painting. However, since there is no confirmed portrait of him, this assumption cannot be pursued further. If at all the painter was allowed to be included in a group portrait of officers and sergeants, presumably this would be in a subordinate position, similar to that of Frans Hals in the group portrait of the Officers and sergeants of the St. George civic guard of 1639 (A2.12). Just as in that painting, Codde may be identical with one of the figures looking towards the viewer. Nevertheless, the seventh figure from the right is too old for Codde, who was born in 1599 and was in his late 30s when the painting was made. Figures no. 12 and 14 are – fortunately for today's interpretation – left largely in the state as was sketched by Hals. Surely, Codde would not have had to kept his own likeness in such a state. In addition, no. 14 shows facial proportions that have not yet been worked out fully (a shifted eye axis and raised right ear) [31]. Either of these portraits would not have escaped Codde's attention and reworking if it had been his own representation, meant for posterity.26

32

Detail of cat.no. A2.11, head of figure 14

A2.12 Frans Hals, his workshop and Cornelis Symonsz. van der Schalcke, Officers and sergeants of the St George civic guard, 1639

Oil on canvas, 218 x 421 cm

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. OS I-113

This latest and largest civic guard portrait by Hals depicts 19 persons in a row, 17 of them officers or sergeants of one of the three companies of the St George civic guard and one from the Calivermen civic guard. The 19th person – the only figure without a status symbol, appearing as the second guardsman from the upper left – is the artist Frans Hals himself. Since the original of his small-scale bust portrait from some years later has not been preserved, but only several copies of it (B17), this is the only authentic self-portrait of the painter.

The sitters are as follows:

1. Johan Claesz. van Loo († 1660), colonel

2. Michiel de Wael (1596-1659), fiscal

3. Quirijn Jansz. Damast (1577-1650), captain

4. Florens van der Hoeff (c. 1600-1657), captain

5. Nicolaes Grauwert (1582-1658), captain

6. Hendrick Pot (c. 1580-1657), lieutenant

7. François Wouters (1600-1661), lieutenant

8. Cornelis Hendricksz. Coning (1601-1671), lieutenant

9. Hendrick Hendricksz. Coning (1604-after 1660), lieutenant

10. Dirck Dicx (1603-after 1650), ensign

11. Lambert Wouters (1602-1655), ensign

12. Pieter Schout, ensign

13. Jacob Druyvesteyn (1612-1691), ensign

14. Gabriël Loreyn (c. 1591-1660), sergeant

15. Lucas van Tetterode (c. 1592-1647), sergeant

16. Nicolaes Jansz. Loo (1607-1641), sergeant

17. Abraham Cornelisz. van der Schalke (1582-1642), sergeant

18. Pieter de Jong, sergeant

19. Frans Hals (1582/1583-1666), painter [33]

The affiliation to the individual companies is indicated by the colors of the sashes: orange, white and blue. Hals created variety by the different turns of the men’s heads, and by the variations in illumination of the figures in the different conversational groups. Part of the group was arranged standing on a ramp above and behind the men in the front. Just how much the civic guard portraits were proof of the sitters’ status, and how much competition there was in this category, is outlined by Koos Levy-van Halm and Liesbeth Abraham.27 For example, sergeant Hendrick Hendricksz. Coning (9), who was originally depicted as a sergeant with the insignia of his rank, a halberd. This is clearly visible in the x-ray that shows the underlying paint layers. Meanwhile, he is now depicted holding a partisan, the attribute of an officer. In fact, Coning was to become a lieutenant with the militia of the Calivermen civic guard in 1639. It is evident that the painting had to pay tribute to this change in status. The visual prominence given to Michiel de Wael (2) is also striking: he stands in the front row, his tan costume contrasting with the black clothing of the men surrounding him. In 1636, De Wael had been promoted by the captain to the new position of treasurer, as indicated by the short commander’s staff that he holds.28 In x-ray, his originally round pleated collar is visible, which was altered into a more fashionable flat lace collar in the final painting.

Several sitters in the present picture also appear in other paintings by Hals, which offers opportunities for comparison the artist’s approach to their portraits. This applies to captain Van Loo (1) (A2.10), fiscal De Wael (2) (A1.22, A1.30), lieutenant and painter colleague Pot (6) (A2.10), lieutenant Wouters (7) (A1.102, A3.50), ensign Dicx (10) (A1.30) and lieutenant Coning (8) (A3.15). In addition, we encounter Michiel de Wael a few years later in the 1642 group portrait of the Calivermen civic guard painted by Pieter Soutman.29

A2.12

33

Schematic representation of cat.no. A2.12

The background depicting a landscape and buildings is only faintly visible today, yet it can be attributed by comparing the details. Gratama’s suggestion that it could have been painted by Cornelis Symonsz. van der Schalcke (1617-1671), a nephew of the sergeant painted as no. 17, was not agreed upon for a long time.30 The reworking of the two buildings in the background by Dirk Maas (1656-1717) in 1706 – as documented in archival sources – must have played a role in this.31 It is unclear how much of the original background is still preserved since this 18th-century campaign. However, a comparison with the two later family portraits from the Hals studio (A4.3.19, A4.3.24), shows a match in the depiction of the foliage, as well as in the dark clouded skies with bright background lighting. The beams of light that are shimmering through reveal that the sky was originally clouded more dynamically. Upon comparison with the accepted oeuvre of Van der Schaclke, the landscapes in the two family portraits can be convincingly attributed to him. Accordingly, he can also be supposed to have been responsible for the background in the present painting, which would then be the earliest known work by his hand.

The width of the picture suggests that most of the figures, especially their faces and hands, must have been executed with the help of intermediate studies. Such direct ‘snapshots’ in a small format, preferably on paper, could represent the single sitters in consistent lighting as close to life as possible. The final composition, which combines all portraits, is executed in a cursory and planar manner, compared to Hals’s individual portraits of the period. It should thus most probably be understood as the result of a simplified transfer of the single facial studies that were made after life. Simplifying means that outlines and shapes were rendered precisely, yet Hals’s energetic brushwork was neglected. The style of painting in the faces, which is more pasty and smoother than in earlier group paintings, as well as the dashed marking of hair areas and shadow zones, reveal the work of an assistant who transferred the facial studies. Hals does not seem to have simulated the use of his own spontaneous manner of execution. The process of binding together individual areas and the resulting levelling of execution would also explain why the most freshly painted representations can be found on the right hand side of the composition. The head and body of ensign Schout (12), outer right, was probably painted onto the canvas directly from life by Hals. Also the second figure from the right, ensign Dicx (10), profited from his marginal position in the composition, as can be seen in the rendering of his facial features and hair, which are largely painted in Hals’s loose manner. [34]

The smoother and more careful arrangement of all other faces and figures, on the other hand, can be attributed to one or more other hands who had to insert the several individual portraits into the final composition, in the correct format, and on the basis of presumably differently detailed models. This probably also applies to the artist’s self-portrait, in which partial and stroked modelling in the hair and mustache can be recognized – clearly deriving from Hals’ approach. Further examples are offered by the heads of captain Grauwert (5) and sergeant Van der Schalcke (17) [35][36]. Standing out from this layer of general execution throughout the whole composition – characterized by an even, impasto application of paint – are the distinctive emphases and corrections that reveal the optical qualities of highlights and shadows, and at the same time, the brushwork of Frans Hals. These can be found in the mouth lines, nose shadows and eye contours and – as in Hals’ self-portrait – in the diagonal streaks of highlights running against the strokes in the mustache and goatee. Such loose reworking is also visible in many hair sections, for instance in the hair of De Wael (2) [37].

A similar sequence of approach can already be observed in the meeting of the officers and sergeants of the Calivermen civic guard, of 1632-1633 (A2.10). But unlike there, Hals has largely retreated from the intensive involvement with details in the present painting. One-and-a-half collar sections (no. 10, 12), two-and-a-half sword handles (no. 5, 12), one sash (no. 12); yet no hand, no glove, no cuff, no halberd, no partisan can be identified as his individual bravura contribution.32 Overall, the painting stands out in its muted tonality and even distribution of color accents, opposed to the agitated composition and spatial grouping of the more colorful representation of the abovementioned Calivermen civic guard. Whoever has assisted Hals in both cases cannot be guessed. In contrast to the commission of 1632-1633, Hals’s sons Frans (II) (1618-1669) and Jan (c. 1620-c. 1654) were active in the workshop as fully trained assistants by 1639.

In comparison to the other group portraits, the appearance of the present picture is somewhat impaired by the cracks in the impasto paint layer.

34

Detail of cat.no. A2.12, ensigns Pieter Schout (12) and Dirck Dicx (10)

35

Detail of cat.no. A2.12, head of Nicolaes Grauwert

36

Detail of cat.no. A2.12, head of Abraham Cornelisz. van der Schalke (17)

37

Detail of cat.no. A2.12, head of Michiel de Wael (2)

Notes

1 The date of 1627 is in accordance with the service period of the sitters, which was 1624-1627.

2 New York 2011, p. 18-19.

3 ‘Daer is van Franz Hals een groot stuck schilderije van einige Bevelhebbers der Schutterije in den Ouden Doelen ofte Kluyveniers, seer stout naer t’leven gehandeld’. Ampzing 1628, p. 371.

4 Biesboer/Köhler 2006, p. 238.

5 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 386, doc. 62.

6 Adriaen Matham, View of the palace of the sultan of Marocco in Marrakesh, 1646, etching and engraving, 580 x 2595 mm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. RP-P-OB-81.619.

7 Sale Amsterdam, 6 August 1810, lot 41 (Lugt 7844); sale Amsterdam, 25 August 1817, lot 33 (Lugt 9208). See: Hofstede de Groot 1907-1928, vol. 3 (1910), p. 32, no. 121c, listing incorrect dimensions; Hofstede de Groot 1921, p. 67-68.

8 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3 (1974), p. 43; sale Amsterdam, 13 August 1806, lot 323 (Lugt 7143): ‘Hals. (F.) / hoog 38, breed 54 duim, [c. 95 x 135 cm] op doek / 323. Een Fruit en Groenteverkoopster; meesterlyk geschilderd’.

11 Biesboer/Bijl 2006, p. 10, 11, 15.

12 Rembrandt, Portrait of Nicolaes van Bambeeck, 1641, oil on canvas, 111,5 x 90,5 cm, Brussels, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, inv.no. 155; the portrait by Rembrandt was only surpassed by its pendant, the Portrait of Agatha Bas, 1641, oil on canvas, 105,4 x 83,9 cm, Great Britain, The Royal Collection, inv.no. RCIN 405352.

13 Dudok van Heel 2017, p. 18.

14 Dudok van Heel 2017, p. 23-24.

15 ‘Magere Compagnie’ (Van Dijk 1758, p. 30).

16 All citations from: Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 391.

17 Dudok van Heel 2017, p. 23-24.

18 Middelkoop 2019, vol. 1, p. 84.

19 Thomas de Keyser, Officers and Other civic guardsmen of the IIIrd District of Amsterdam, under the Command of Captain Allaert Cloeck and Lieutenant Lucas Jacobsz Rotgans, dated 1632, oil on canvas, 220 x 351 cm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. SK-C-381.

20 Van Eeghen 1974, p. 138-140.

21 X-ray illustrated in Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 106-107.

22 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 103-108.

23 Middelkoop 2019, p. 799.

24 Govert Flinck, Portrait of a man, 1639, oil on canvas, 76.5 x 63.5 cm, private collection.

25 Rembrandt and studio, Portrait of Jean Pellicorne and his son Casper, c. 1633, oil on canvas, 155.5 x 123 cm, London, The Wallace Collection, inv.no. P82; Anonymous, Portrait of Pieter Ranst, oil on canvas, 116.5 x 87 cm, sale Paris (Drouot), 24 June 1998, lot 16.

26 Middelkoop 2019, p. 799 suggest that figure no. 14 is possibly Pieter Codde.

27 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 95-100; Biesboer/Köhler 2006, p. 486.

28 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 99.

29 Pieter Soutman, Officers and sub-alterns of the Calivermen's civic guard, 1642, oil on canvas, 203 x 344,5 cm, Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. OS I-314.

30 Gratama 1946, p. 41; Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3 (1974), p. 67.

31 Biesboer/Köhler 2006, p. 486.