A3.19 - A3.29

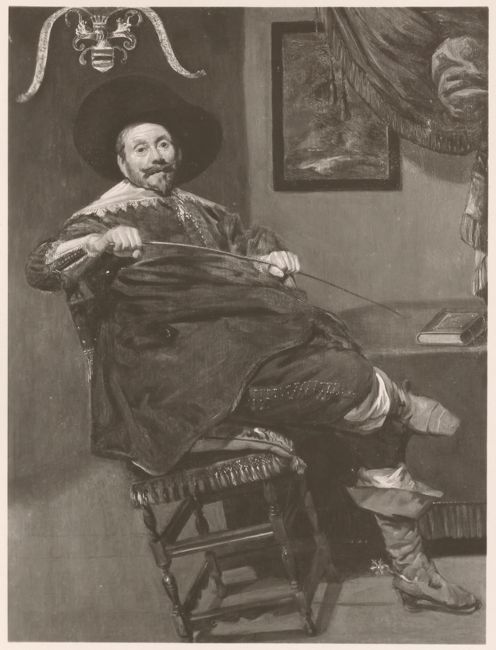

A3.19 Frans Hals and workshop, possibly partly reworked by Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck, Portrait of Nicolaes Woutersz. van der Meer, 1631

Oil on panel, 128 x 100.5 cm, inscribed and dated upper right: AETAT SVAE 56 / AN° 1631

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. OS I-117

Pendant to A3.20

Nicolaes Woutersz. van der Meer (c. 1574-1637) was a brewer in Haarlem, who repeatedly held honorary positions as a lay judge and as mayor, the latter in 1618, 1620, 1628, 1629, 1634 and 1635. Frans Hals had painted him earlier in the central foreground of the 1616 Banquet of the officers of the St George civic guard (A2.0). On 9 August 1598 Van der Meer married Cornelia Claesdr. Vooght (* c. 1578). Through this marriage Van der Meer became brother-in-law to Pieter Jacobsz. Olycan (1572-1658), politically the most influential member of the Haarlem brewer family who gave commissions to Hals throughout his active period (A3.25, A3.32 and A3.33).

In the present painting, the posture of Van der Meer follows an established type; Hals had adopted it in a similar way for the Portrait of an elderly man in the Frick Collection (A1.41). Even though the presentation of the standing body with the hand on a chair is close to previous portraits by Flemish painters – especially several of Anthony van Dyck's (1599-1641) compositions – a comparison with their glorifying elegance highlights the sobriety of Frans Hals's observation at close quarters. However, the present picture and its pendant (A3.20) differ in several respects from Hals’s autograph portraits from the 1630s. Scientific research showed that the heads of the sitters were overpainted after completion. The top layer of paint in these sections was painted over a layer of varnish.1 The realistic smoothness of the wall’s appearance is probably due to the same reworking process. I would assume that the background in the present painting was originally lighter and more diffuse.2

In both paintings, the faces were reapplied in an enamel-like painterly style with nevertheless subtly differentiated coloring. On close inspection, it becomes clear that the man’s head is executed in a consistent style on top of the underlying painting. The smooth skin throughout and the waxy beard area structured with only a few hair lines document a fijnschilder type of illusionism which differs from Hals’s sketch-like brushstroke [1]. On the basis of my observations of the removal of overpainting of the Portrait of Pieter Jacobsz. Olycan (A3.25), as well as additional comparisons, I have now come to a different conclusion from my assessment of 1989.3 I am convinced that the overpainting in both paintings is certainly not by Frans Hals, even though it is cleverly done. Stylistically, the second version of the faces visible today can be attributed most likely to the Haarlem portrait painter Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck (1601/1603-1662).

It is not clear why the present painting and its pendant were reworked. A drawing after the female portrait, created by J. van der Sprang in 1762 (D9), shows the painting in its present state, suggesting a 17th-century execution. Curiously enough, the portraits of the Van der Meer couple share the fate of reworking with several portraits of close relatives of them, executed by Hals. The Portrait of Pieter Jacobsz. Olycan (A3.25) and the 1639 pair of Olycan and his wife of 1639 (A3.32, A3.33) also suffered a smoothing reworking of the facial features. Unfortunately, no pigment samples were taken from the overpainting in Olycan's portrait of 1634-1635 (A3.25), which has been successfully removed during treatment by Martin Bijl. This would have made a comparison with the pigments of the portraits of Van der Meer and Vooght possible.

In the present picture, the collar area is of lesser quality; it is applied more coarsely and less accurately than in corresponding examples from Hals’ other works from this period, for instance the collar of the Portrait of an elderly man in the Frick Collection (A1.41). The collar in the Portrait of Pieter Jacobsz. Olycan (A3.25) is also more confidently captured in the foreshortened side edges [2][3].4 The collar was probably painted by an assistant of Hals, whose viscous application of paint is also apparent in the creamy overpainting of the fingers, the accents on the fingernails, the strengthened contours of the cuffs as well as the lion’s head on the back of the chair. In contrast, Hals’s brushwork is still visible in the soft contours of the brushstroke around the finger joints, especially in the left hand.

As is the case in a number of Hals's portraits (A1.65) - especially several portraits from the Olycan family (A1.17, A1.18, A1.93 and A1.94) – the coats of arms in the portraits of Van der Meer and his wife were added at a later date. Chemical analysis of the pigments identified the presence of the pigment Prussian blue, which only came onto the market in the early 18th century.5

1

Detail of cat.no. A3.19

2

Detail of cat.no. A3.19

3

Detail of cat.no. A1.41

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of an elderly man, c. 1627-1628

New York, The Frick Collection

© The Frick Collection

A3.19

A3.20

A3.20 Frans Hals and workshop, possibly partly reworked by Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck, Portrait of Cornelia Claesdr. Vooght, 1631

Oil on panel, 126.5 x 101 cm, inscribed and dated upper left: AETAT SVAE 53 / A° 1631

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. OS I-118

Pendant to A3.19

As is the case with the companion piece (A3.19), the Portrait of Cornelia Claesdr. Vooght was reworked after completion. Technical research showed that the top layer of certain parts is painted on top of a layer of varnish. Hals’s own brushstroke is recognizable in the eyebrows, the areas of the eyes and eyelids, the shadow of the nose, the upper lip, the hairline, and the white bonnet [4], but also the execution of the collar, the arms and hands and the cuffs. In contrast, overpainting is noticeable in the temple, the cheeks, the lower lip, the chin area, the rounded cast shadow of the nose and in the insertion of smoothly applied creamy reflections on the nose, the chin, the corner of the mouth and above the cheeks. It is apparent that these smoothing interventions are applied over the execution that is typical for Hals. The overpainting is also visible in the collar and the background.

An X-ray of the head of Vooght showed that her face was originally narrower and smaller, the collar less wide, and the bonnet larger. The proportion between the face and figure in both its current as well as its original state is unusual. While the head of her spouse in its present appearance is now just about imaginable, the woman’s head is comparatively small. The same disproportion is visible in comparison to the size of her hands, which cannot be found in any other autograph female portrait by Hals.

The angular reflections on the lion’s head in the back of the chair are created quite similarly to the pendant [5].6 The fur trim is executed in regular, somewhat hard stripes. In the same manner, the folds of the black skirt are suggested by a pattern of impasto brushstrokes which lack the sophisticated plasticity of comparable executions by Hals. While the smoothing of the face can be attributed to the same hand as that of the overpainting in the face of the pendant – most likely Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck (1601/1603-1662) – the impasto execution of the remaining areas cannot be attributed in the same way with certainty.

An interesting comparison of the execution opens up if one post-exposes the folds of the dark skirt in this picture and compares them to the similar parts in Hals' 1633 Portrait of a woman (A1.57). The rhythmic arrangement of the folds there and their plasticity are contrasted here with a flat hick-hack of lighter and darker stripes [6][7].7

4

Detail of cat.no. A3.20

5

Details of cat.no. A3.19 and A3.20

6

Detail of cat.no. A3.20

A3.21 Frans Hals and workshop, Portrait of a man, c. 1633-1634

Oil on canvas, 66.5 x 48.5 cm, monogrammed center right: FH

Buenos Aires, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, inv.no. 8626

This portrait fits perfectly into Hals's oeuvre and only there. It had not been seen in a long time and was unfortunately only documented in mediocre black-and-white illustrations. In 1928, Valentiner published it in his article ‘Rediscovered paintings by Frans Hals’ and some years later he included it in his exhibition of 50 Frans Hals paintings in Detroit.8 By then it was part of the collection of Charles F. Williams in Cincinnati. During the 1937 exhibition in Haarlem it was on loan from the Howard Young Galleries, New York, and London.9 Slive rejected the picture and excluded it from his publications.10 The museum of Buenos Aires accordingly catalogues it as the work by an anonymous Dutch artist.11

On close inspection of the details of the execution, Hals’s lively brushwork is mostly absent in this portrait. While the folds of the sleeve are described anatomically correct, there is no rhythmical emphasis on dark areas and light edges. In the same way, the lace of the collar was convincingly captured in its illumination and alternating arrangement, but this was done in short linear brushstrokes and without an underlying swift movement of the brush. Similarly, the modelling of the hand seems rather imitated than spontaneously applied. Hesitant shaping is also noticeable in the facial area and the hair [8]. Nevertheless, the sum of these elements results in a capturing of facial features which is typical for Hals, and only for him. This impression can be explained on the one hand by the extensive imitation of a portrait study by Hals, probably done on paper. On the other hand, Hals himself added decisive visual accents. These can be found in the outline of the eyes, the line of the mouth, and the accents in the hair and moustache. The psychological presence of the sitter is due to these interventions.

A3.21

8

Detail of cat. no. A3.21

A3.22 Frans Hals and workshop, Portrait of Willem van Heythuysen, c. 1634-1635

Oil on panel, 47 x 36.7 cm, monogrammed lower right: FH

Private collection

This is the second portrait of the textile merchant Willem van Heythuysen (c. 1585-1650), following the large full-length depiction of 1625-1626 (A2.6). The sitter is represented in riding clothes, wearing boots with spurs. In his outfit of a country gentleman, he seems to have entered the room in order to sit for his portrait. The posture with the crossed-over leg is in keeping with depictions of cavaliers in contemporary pictures of elegant companies. Slive refers to the assessment of such portrait positions by the Italian art writer Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo (1538-1592), who would have diagnosed a breach of decorum in the present example.12 It is characteristic for Hals’s ‘realism’ that he adopted the conventional poses – he certainly owed this to his patrons – but that he nevertheless captured his sitters convincingly in their spontaneous actions. Heythuysen is turning his head and eyes in a slightly bored manner in the direction of the viewer. The question ‘How long do I have to hold this pose for?’ might be on his lips. His inner tension is diverted towards the riding crop between his hands. Hals’s observation of situational behavior captures something spontaneous and typical. At the same time, his widely drawn contour lines create a visual field of corresponding directions of movement, centered on the illuminated face as if on a source of energy.

The superiority of this portrait compared to the other versions, the convincing resemblance of the present face to that of the Munich painting, and the compositional changes apparent in pentimenti, proclaim the present picture to be the original model for all other versions. The areas of the head and hands display Hals’s soft and confidently accentuated brushwork. The body and the background were most likely executed by an assistant on the basis of Hals’s preparatory drawing, which is visible at close range as contours. Dark contour lines are recognizable along the floorboards, the frame, and the curtain in the background, as well as on the outline of the figure and the seam of the tablecloth. In contrast, work by an assistant is indicated in the mechanical execution of the small buttons, the hard folds of the coat and the top boot on the outstretched foot. This also applies to the angular folds of the gathered curtain on the right and the stiff fringe on the chair. The juxtaposition of such traces of execution and of pentimenti such as the correction of the hat, illustrates the process of creation. They reinforce the impression that the present picture was painted in a collaboration between the master and an assistant.

Stylistically, the painting can be dated to 1634-1635. Martin Bijl observed that the panels used for paintings in Haarlem were sawn by hand until c. 1634. Afterwards, they consistently show the marks from a sawmill. This is already the case for the workshop replica in private ownership (A3.23), while the present picture still shows marks of the hand saw.13

The inventory drawn up after Heythuysen’s death in 1650 lists a ‘small likeness of the deceased, in a black frame’, which hung in a private room in the sitter’s house. Twice, the picture achieved a record price on the art market: in 1865 in Paris at 35.000 Francs and in 2008 in London at seven million pounds. Several repetitions of the composition have been preserved, which can be dated justifiably to the 17th century (A3.23, A3.24).

A3.22

A3.23 Workshop of Frans Hals, Portrait of Willem van Heythuysen, c. 1635-1653

Oil on panel, 46.2 x 36.2 cm

Sale Pfarrkirchen (Reibnitz), 2 March 2007, lot 400

Dendrochronological examination could only determine a felling date after 1599 for this panel. An analysis of the pigments revealed pigments typical for the 17th century.14 The appearance of this variant is closer to the original version (A3.22) than to the one in Brussel (A3.24). The paint layer appears to be thinner than that of the Brussels variant and is stylistically different – as such, it must have been executed by a different hand. Most probably, the present painting was created in Hals’s workshop in parallel to the first version or based on the same preparatory design. Martin Bijl’s observation that the panel of the present picture already displays traces of having been cut in a sawmill, indicates a follow-up commission that was ordered after c. 1634.

The inscription on the back commemorates Heythuysen’s personal achievements: ‘Willem van Heythuyzen, Protestant left Flanders on account of his Religion & brought over with him 28 Families into Holland some of which afterwards settled in England’. The fact that the picture first appeared in an 1893 London sale, suggests the possibility that Van Heythuysen ordered it himself for his contacts in England.15

A3.23

A3.24 Workshop of Frans Hals, Portrait of Willem van Heythuysen, c. 165316

Oil on panel, 47.5 x 37.5 cm, monogrammed lower right: FH

Brussels, Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, inv.no. 2247

Availability of all three versions of the portrait of Willem van Heythuysen, their scientific examination and restoration have led to a clarification of the sequence of creation and the historical authenticity. Dendrochronology has determined a date of creation not before 1650 for the Brussels picture.17 The identification of a receipt for a payment of 36 guilders from Maerten van Sittard to Frans Hals proved the Brussels picture to be a later copy.18 Van Sittard was a relative of Heythuysen and one of his executors. This is the only documented case of a preserved copy made in Hals’s workshop. The inscription on an old label on the reverse of the panel confirms the purpose of the commission to be the commemoration of the founder of the residential complex Hofje van Heythuysen: ‘Willem van Heijthuysen/ Stichter van dit Hofje/ Overleden den 6. July 1650’.

This version is close to the original, but coarser in some details and less astute in three-dimensional representation. The difference is most noticeable in the essential portrait areas of face and hands. In the original, these were contributed by the master. The similarity suffers in particular from the too-wide area around the eyes, which is more clearly designed in the first version (A3.22) and corresponds better with the large-scale Munich portrait as well (A2.6) [9][10][11]. In most cases, the production of copies after 17th-century paintings was delegated to workshop assistants. Based on a comparison of the details of the execution and in contradiction with previous literature, the same approach can be assumed in this instance.

A3.24

Photo: J. Geleyns

9

Detail of cat.no. A3.24

10

Detail of cat.no. A3.22

11

Detail of cat.no. A2.6

Frans Hals (I)<Portrait of Willem van Heythuysen

Munich, Alte Pinakothek

A3.24a Workshop or follower of Frans Hals, Portrait of Willem van Heythuysen

Oil on panel, 46 x 36 cm

Sale Cologne, 20-23 October 1965, lot 133419

As far as discernible from a photograph, the representation is mostly similar to that of the original version (A3.22), yet the facial features are especially close to the second version (A3.23). In the existing photographs, neither the inscription on the ribbons on the side of the coat of arms nor the coat of arms as such are legible. The bars in the shield of the coat of arms may refer to the same bars as those in the coat of arms on the upper left corner of Heythuysen’s tomb slab in the church of St. Bavo in Haarlem.

A3.24a

A3.24b follower of Frans Hals, Portrait of Willem van Heythuysen, possibly 19th century

Oil on canvas 54 x 41 cm20

France, private collections

The high price of 4.650 francs that was achieved for this painting at the 1870 Peletier auction is remarkable.21 This copy could well date from the period of Hals’s rediscovery at the time, which would be consistent with the canvas support – instead of the panel of the other versions. Also in accordance would be Slive's reference to a copy after the Brussels picture that was created by the painter Pieter Ernst Hendrik Praetorius (1791-1876), by his own account in 1865/1866.22

A3.25 Frans Hals and workshop, Portrait of Pieter Jacobsz. Olycan, c. 1634-163523

Oil on panel, 68 x 56.6 cm

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. OS-2004-39

Pendant to A3.33a [12]

Due to its condition and the lesser quality of execution of the pendant (A3.33a), art historians considered this painting to be a weak variant of Hals's 1639 Portrait of Pieter Jacobsz. Olycan (A3.32) – even though it was appreciated by some connoisseurs. The restoration by Martin Bijl and an examination of the historical context have now allowed this portrait to be adequately categorized. The current bust-length portrait was cut down from probably an original standing three-quarter length figure. Scientific examination revealed that the panel was trimmed soon after its execution – probably due to damage. Bijl dated this intervention no later than 1635, based on the character of the cuts of the saw.24 After the painting was reduced in size, new compositional elements were added to the dry but as yet unvarnished paint layer, depicting a now more upright collar – instead of resting on the shoulder – and the present black coat and the arm with the hand just disappearing under the edge of the fur trim. This hand, which was only underpainted and not clearly defined, had for Slive been the downfall in the picture’s categorization, as it could not have been painted by Hals himself.25 It is not known who was responsible for the new design of the hand and coat areas in such an uninspired manner, but it must have probably been done during the 17th century, since the watercolor copy by Wybrand Hendriks (1744-1831) already shows the state of the painting in which it is still visible today (D24).

In today’s condition, the painting shows in part the confident brushwork of Hals – in the shadowed side of the forehead, and in the contouring of the eyes, nose, and mouth – but predominantly, it displays a smoother and softer handling. This includes smoothing overpainting in the area of the head, such as on the ear, the eyelids, the nose, the cheeks, and the lip. Hals’s brushwork was also later attenuated in the hair on the head and in the moustache. A further phenomenon is the strengthening of the whitening of the hair of the head and the beard which emerged in this early Olycan portrait over the course of several reworkings and restorations. The thinly applied brown and grey tones were partly dissolved and thinned down while the opaque lead white lines gained preponderance. The result is that the sitter’s full hair seems more silvery and brushed smoothly than in the unkempt appearance of 1639 [13][14]. Finally, the design of the collar also deviates from the accurate modelling we see in contemporary examples.

Biesboer dated the picture around 1629-1630, since Olycan had first become mayor in 1630.26 However, Hillegers moved it closer to the portrait in Sarasota, whose facial features it closely resembles (A3.32).27 Indeed, the loose brushwork and the modelling details of the facial features support a date of creation not far removed from the Portrait of Pieter van den Broecke (A1.58), Portrait of Nicolaes Hasselaer (A1.62) and the Portrait of Tieleman Roosterman (A1.65), all three dated 1633 and 1634.

13

detail of cat.no. A3.25

14

detail of cat.no. A3.32

Frans Hals (I) and workshop

Portrait of Pieter Jacobsz. Olycan

canvas, oil paint, 111.1 x 86.7 cm

Sarasota, The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, inv.no. SN251

© Collection of The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, the State Art Museum of Florida

A3.25

12

attributed to Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck

Portrait of Maritge Claesdr. Vooght

panel, oil paint, 68.5 x 57.8 cm

sale New York (Sotheby’s), 6 June 2012, lot 36

cat.no. A3.33a

A3.26 Frans Hals and workshop, Portrait of a woman, 1634

Oil on canvas, 111.1 x 83.2 cm, inscribed and dated upper left: AETA SVAE 28 /AN° 1634

Baltimore, The Baltimore Museum of Art, inv.no. 1951.107

Pendant to A1.68 [15]

Slive's suggestion that the present painting and the 1634 Portrait of a man in Budapest (A1.68) could be pendants appears entirely convincing, judging from the matching costumes and the reconstruction of the original size of the male counterpart.28 The friendly, yet reserved and understanding expression of the woman fits quite well as a complement to the somewhat stilted appearance of the man.

When studied up close, the woman’s hands, pearl necklace, cuffs, and the overall dress, including the collar and lace cap, appear to have been painted by an experienced workshop assistant. Only a few touches of revision by the master can be discerned. The surface of the face seems to have been smoothed in some areas. The paint has been applied in an impasto manner, causing a comparatively pronounced craquelure pattern.

15

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of a man, dated 1634

Budapest, Szépmüvészeti Múzeum, inv./cat.nr. 4158

© Museum of Fine Arts Budapest

cat.no. A1.68

A3.26

The Baltimore Museum of Art: The Jacob Epstein Collection, BMA 1951.107; photograph by Mitro Hood

A3.27 Frans Hals and workshop, Portrait of a man, c. 1634-1635

Oil on canvas, 78.9 x 66.1 cm

Sale London (Sotheby’s), 7 December 2022, lot 5

This painting was cut slightly along the lower edge. At first, the smooth execution of the jacket, but also of the collar and the two-dimensional area of the face seem atypical for Frans Hals. This may be the reason why Slive classified it as a work by an imitator.29 Nevertheless, the central area of the face is absolutely typical for Hals. The accuracy of a few brushstrokes that capture the merry and animated expression around the eyes, nose and mouth indicates that Hals designed this picture and summarily executed the area of the face. Consequently, this area remained with thin paint layers and just a few accents of light and shadow. The remainder of the portrait was executed subsequently and more hesitantly by the hand of an assistant.

A3.27

Photograph Courtesy of Sotheby’s, Inc. © 2023

A3.28 see: A1.72A

A3.29 Frans Hals, his workshop and Pieter de Molijn, Portrait of Nicolaes van den Heuvel, Susanna van Haelwael and their eldest children, c. 1635

Oil on canvas, 111.8 x 89.9 cm

Cincinnati, Cincinnati Art Museum, inv.no. 1927.399

This small-scale depiction of a full-length family group combines elements of portraiture with those of interior and landscape painting, but also still life. The four figures are arranged next to each other on the terrace of a manor house. Behind them, chairs are visible that were pushed back from a table. The tabletop appears next to the shoulder of the seated woman, covered with an oriental carpet. On top of it, a glass of wine and an orange indicate a possible ceremony, combined with a Eucharist symbolism in the wine catching the light, and the meaning of the sweet fruit of the certitude of faith. The older child is holding an orange with one hand and grabs its younger sibling with the other. As outlined by Slive, the gestures of the parents are typical expressions of love and friendship, going back to Cesare Ripa’s 1644 Iconologia.30 The viewer is presented with a sort of pantomime, as the smile of the mother in the center is directed at them, whilst her proper left hand points towards her husband. The other family members are looking at each other and turn lovingly towards one another. Similar to the Portrait of Willem van Heythuysen (A2.6), the standing gentleman is seen against a background of red drapery; in both pictures elements of stately architecture can be seen on the side and behind the drapery. As in Van Heythuysen’s portrait, there are roses in the foreground – rendered in a somewhat stiffer manner – which most likely indicate the joy of life and transience.

In 2021 Frans Grijzenhout identified the sitters to be the Haarlem yarn merchant Nicolaes van den Heuvel (c. 1603-1661), his wife Susanna van Haelwael (1606/1607-1667) and their two children.31 The man's clothing, without cuffs, identifies him as a Mennonite. The identification of this painting, created around 1635, challenges the comparison with the Family portrait created in 1654 by Adriaen van Ostade (1610-1685), which has survived as a depiction of the same parents with their then larger crowd of children [16]. The latter painting, however, is much smaller and includes a much larger group of people positioned in the middle-ground of the composition, which reduces the size of the individual faces and limits their comparability. Yet, despite the somewhat simplified rendering in the later painting, the identification of the parents is clear. The portrait of the father must have been based on Ostade's own designs, while the mother's face may have been taken from Hals's earlier work. On the basis of this confirmation, Grijzenhout was able to identify the children depicted in both family portraits and thus deduce the date of origin of Hals's family group. Since the couple's eldest daughter, Maria, was born in 1629 or 1630, and the next children in the 1654 family portrait were significantly younger, the little girl in Hals's portrait had to be the child whose burial is attested on December 6, 1636. This would then be the terminus ante quem for the commission.

It can be assumed that the entire composition and the initial modelling of the figures have been done by Hals himself. The brightest parts of the portrait are the faces and hands, which, however, vary in quality. The faces of both parents were probably based on individual studies by Hals and executed by him for the most part, while the clothing including collars, all hands and the children’s faces are executed by a weaker hand – or even by two weaker hands. The very ‘Halsian’ design of the well-proportioned parents’ figures is remarkable and contrasts with the clumsy hard lines of light and shadow on the children’s clothing. Illuminated areas and folds in the shadows of the parents’ clothing are, however, more even in their brushwork. It seems reasonable to assume that preparatory drawings or paintings created after life as ‘snapshots’ were available for these areas, including the faces and hands, and were subsequently copied in proportion into the painting.

On the right-hand side of the composition a view towards a manor house and a church tower are visible, which have not yet been identified. The slightly abraded paint surface in this area also makes it harder to identify the painter’s hand. Just like other backgrounds in Hals’s works, the brushwork clearly differs from his own. However, the depiction of the trees and the foliage in the typical finger-like shapes corresponds to the style of Pieter de Molijn (1595-1661). It is interesting to note that infrared-reflectography found an underdrawing of the background, probably done in black chalk. However, in the absence of matching comparisons, this does not provide enough information about the exact sequence of steps in the working process, and even less about those involved in the execution.

A3.29

16

Adriaen van Ostade

Family portrait in an interior, dated 1654

Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv./cat.nr. 1679

© 2014 RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Michel Urtado

Notes

1 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 249.

2 From the darkening of the setting, Slive concluded a change in Hals’s style at the beginning of the 1630s (Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 248).

3 Grimm 1989, p. 182, no. 56, 57.

5 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 121, 248.

8 Valentiner 1928, p. 248, fig. 6; Valentiner 1935, no. 32.

9 Haarlem 1937, no. 59.

10 Oral communication between Seymour Slive and Claudia Caraballo de Quentin, 23 April 1991.

11 Website Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires, accessed 25 October 2022.

12 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3 (1974), p. 66.

13 See also London/The Hague 2007-2008, p. 118, note 10.

14 Middelkoop/Van Grevenstein 1988, p. 97; Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 276-277; London/The Hague 2007-2008, p. 241, note 6.

15 Sale London (Christie, Manson & Woods), 24 June 1893, lot 21 (Lugt 51887).

16 Based on the documentation delivered in 1653.

17 London/The Hague 2007-2008, p. 118.

18 Biesboer 1995, p. 120-121.

19 Provenance, according to private communication with a relative of the former owner: formerly Uccle (Brussels), property of Michel van Gelder and Leo Nardus (since 1908); confiscated by the German occupying forces in 1940, auctioned by Lempertz, Cologne, in 1943, claimed for restitution in 1948; whereabouts unknown since then.

20 Slive erroneously records the size as 52 x 62 cm (Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 276, 278, note 1, ill. 51b).

21 sale Paris (M. Peletier), 28 April 1870, lot 12 (Lugt 31982).

22 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 278.

23 On the basis of dendrochronological examination, the sawing marks and stylistics datable to c. 1634-1635.

24 Biesboer/Bijl 2006, p. 19, 21.

25 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 69.

26 Biesboer/Bijl 2006, p. 9.

27 Haarlem 2013, p. 138.

28 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3 (1974), p. 55.

29 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3 (1974), D 50.

30 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 270.

31 Grijzenhout 2021, p. 170-189.