A4.2.21 - A4.2.30

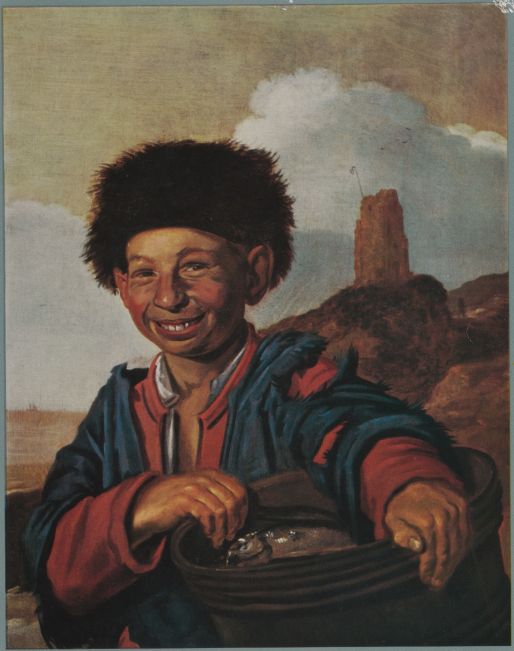

A4.2.21 Workshop of Frans Hals, Fisherboy with a basket in a landscape, c. 1636-1638

Oil on canvas, 74.1 x 60 cm, monogrammed lower left: FH

Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland, inv.no. 193

Together with the figures of the fishergirls in New York (A4.2.19) and Cincinnati (A4.2.23), the present fisherboy is quoted in the Beach scene with fisherfolk (B14), attributed to Jan Miense Molenaer (c. 1610-1668).

Judging from the hard contours of this fisherboy’s clothing and the angular modelling of the face, he was probably painted by the same hand as the boy in Antwerp (A4.2.20). The arrangement of the steeply sloping dunes is similar as well, albeit in reverse. The facial features are only captured in the outer contours and the main lines in the face. Subtle movements in the expression are excluded. A cursory brushstroke suggests the face, the jacket, and the basket. Hals's own contribution may have consisted of the design of the composition and the creation of studies for the face.

A4.2.21

Photo © National Gallery of Ireland

A4.2.22 Workshop of Frans Hals, possibly Frans Hals (II), Fisher girl with a basket, c. 1636-1638

Oil on canvas, 65.5 x 56 cm

Cologne, Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, inv.no. WRM 2531

The way the face is painted in this depiction of a fishergirl by the coast, is similar to that of the fishergirl (A4.2.19) and Malle Babbe (A4.2.31), both in collections in New York. The execution of the blouse, with its uniform white brushstrokes, also connects it with the Fishergirl in Cincinnati (A4.2.23). Slive listed two more coarsely painted variants, which are included in the present catalogue for the purpose of reconstructing the original appearance of the Cologne picture. Both variants show the composition with more space on the right-hand side, and both hands of the girl. In the unsigned version (A4.2.22a), the background was altered, but the basket with the proper left hand of the sitter on its edge is identical. In the present picture, this area is unaccountably blurred into darkness. Also, the left and lower edges appear to have been cut. It seems highly likely that the original format corresponded to that of the two subsequent variant. A comparison between the unsigned variant and the Cologne painting, clarifies that the white cloth of the collar, which formerly fell onto the chest, was partly painted over in the latter. Likewise, the sleeve and the cuff were covered up. Furthermore, the hat in the Cologne picture was reduced in size: in both the unsigned and the signed variant (A4.2.22b), it has a wide brim. The present painting was probably similarly monogrammed as the latter, the signature would have been located in the part that was cut off. Recently, X-ray examination was able to reveal these correlations, and at the same time ruled out the suspicion that the Cologne picture might be a later copy.1

A4.2.22

© Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln, Rolf Zimmermann, rba_c011279

A4.2.22a Workshop of Frans Hals, Fishergirl with a basket, c. 1636-1638

Oil on canvas, 69 x 64 cm

Sale London (Sotheby’s), 3-4 December 1997, lot 37

From the 1997 sale catalogue: ‘A technical examination of the Henle picture, however, has shown that there is no evidence of it being later than the early 18th Century. In particular, the use of azurite among the charcoal black and lead white in the sky, and the Napels yellow of the basket, make it very unlikely that the painting could be from the latter part of the 18th Century or later.’

A4.2.22a

A4.2.22b Workshop of Frans Hals, Fishergirl with a basket, c. 1636-1638

Oil on panel, 32.0 x 27.5 cm, monogrammed lower right: FH

Sale Vienna (Dorotheum), 10 November 2020, lot 72

A4.2.22b

© Dorotheum, Vienna

A4.2.23 Workshop of Frans Hals, possibly Frans Hals (II), Fishergirl with a basket on her head, c. 1636-1638

Oil on canvas, 76.5 x 62.9 cm, monogrammed lower left: FH

Cincinnati, Cincinnati Art Museum, inv.no. 1946.92

In the present painting, the white cloth of the collar, which was overpainted in the previous picture, is the bright center of attention. The manner of execution, with its uniform brushstrokes, hard contour lines and disintegration of the motifs into individual brushstrokes, is similar to that of the majority of the half-length figure paintings in this group. This is especially apparent in the modelling of the hands and the face.

While Slive considered the present painting to have been created by a later follower of Frans Hals, I would assess the idiosyncratic, bold style of painting as an original achievement by an assistant in Hals's workshop.2 The monogram forms part of the original paint layer and therefore, the picture illustrates the production method in Hals's workshop of the late 1630s – together with the Fishergirl in New York (A4.2.19), and the two Fisherboys in Antwerp (A4.2.20) and Dublin (A4.2.21). I concur with Slive that the style of painting is close to that in the Cologne Fishergirl (A4.2.22) and the New York Malle Babbe (A4.2.31), but in my opinion the same manner is present in the New York Fishergirl (A4.2.19). In all these cases it can be supposed that assumed the execution was carried out by a relatively independent hand within the workshop. Accordingly, one should assume that within Hals's workshop, the production of paintings with marketable subjects was delegated.

In the brushwork in the abovementioned paintings, there is a notable similarity, characterized by the exaggeration and hardening of Hals’s precise application of paint. Contrasts become over-emphasized, especially in the peripheral areas of the clothing, while the faces are handled carefully, avoiding stark contrasts. In consequence, the facial features no longer form the center of energy and minute movement. Notwithstanding these remarks, the unrestrained style of painting in the fisherchildren and other genre paintings anticipates late 19th and early 20th century style of painting to an astonishing degree.

A4.2.23

A4.2.23a Follower of Frans Hals, Fishergirl with a basket on her head, 19th century

Oil on canvas, 25.3 x 19.5 cm

Stockholm, Hallwylska Museet, inv.no. XXXII:B.105._HWY

What had been considered a partial copy of the fishergirl in Cincinnati (A4.2.23), was more recently revealed to be a replica that was cut on all four sides. As the scientific examination of the pigments found traces of zinc white, which became only available from 1840 onwards, it is clearly a later copy.3

A4.2.23a

Photo: Motzkau, Holger, Hallwylska museet/SHM

A4.2.24 Workshop of Frans Hals, Fisherwoman, c. 1636-1638

Oil on canvas, 81.5 x 64.5 cm

Sale Paris (Drouot), 5 December 1980, unknown lot

This painting had not been recorded in the literature prior to its reappearance on the art market in 1976. In terms of subject matter, it can be connected to the other half-length depictions of fisherfolk, which represent the work and happy disposition of the people who fight the natural elements every day of their lives.

A4.2.24

A4.2.25 Workshop of Frans Hals, Fisherboy with a basket on his back, c. 1636-1638

Oil on canvas, 65.4 x 58.7 cm, monogrammed lower right: FH

Allentown Art Museum, Samuel H. Kress Collection, inv.no. 1961.036 000

Slive noted the reduced size of this painting, indicated by the cut-off figure in the upper left-hand corner. The picture has a recognizably independent style that was developed using Hals’s compositions. Nowhere else was the diagonal composition maintained as mechanically as in this case. The falling line of the dunes on the one hand, and the folds of the shirt and the lines of the fingers on the other are all conspicuously emphasized. The face is carved out in a few angular accents. The boy’s expression has not been coordinated with the movement that is visible in the body, but rather only shows a slightly tense smile. The background landscape with its minute details is certainly by another hand, as Colin Eisler noted.4

A4.2.25

A4.2.26 Workshop of Frans Hals, possibly Frans Hals (II), Fisherboy, c. 1636-1638

Oil on panel, 49 x 67.5 cm

Eindhoven, private collection

In its subject matter and manner of execution, this painting follows similar models, such as the Fisherboy in a landscape in Antwerp (A4.2.20). The creation of the background and the style of painting are closest to the Manchester Fisherboy (A4.2.28). Slive noted the severe damage the paint layers sustained during World War II, and the painting’s precarious overall impression after more recent restorations. The most viable illustration of the picture in its undamaged state can be found in the 1937 exhibition catalogue.5

A4.2.26

A4.2.27 Workshop of Frans Hals, A fisherboy, c. 1636-1638

Oil on canvas, 82.1 x 65.9 cm

Raleigh, North Carolina Museum of Art, Samuel H. Kress Collection, inv.no. GL 60.17.67

Slive pointed out the noticeable changes in the popularity of the depictions of fisherchildren. They enjoyed obvious popularity in Hals’s time and afterwards but would only achieve minimal prices by the end of the 18th century.6 Hals’s rediscovery in the late 19th century would also sweep up this group in the vogue for all things painted sketchy and coarsely. The career of the present picture is a case in point. It is painted routinely and economically, and is probably identical with (or a variant of) a work sold in Amsterdam in 1799 for five guilders and four stuivers.7 In 1920, it achieved the considerable price of 4800 guineas, and it was acquired by the Kress Foundation in 1933.8 At the time, it was considered to be an authentic painting by Frans Hals, and was still listed as such in the museum catalogue of 1960.9 However, by 1974 Slive described it as a follower’s ‘coarse imitation'.10 In the more recently published collection catalogue of 2009 it is listed as made by an imitator of Hals.11 This stylistic diagnosis is indisputable. Nevertheless, there is no reason to assume an imitator somewhere outside of Hals’s workshop. Pictures of this type were only developed using Hals’s template and within a limited period of time. This is also evident in the background landscape, which matches that from other paintings painted in Haarlem in the mid-17th century. Moreover, its consistency suggests it was painted by another hand than the figure. The canvas has probably been cut at an angle and re-stretched at some point, resulting in the noticeably skewed horizon. Undeniably, there is a clear difference between the coarse-edged figure in the present painting and Hals's own style. Despite this, the group of fisherchildren paintings, with their 'late Impressionist' style, is derived from concepts and a painterly style developed by Hals. This example also demonstrates the significant tolerance the master had for workshop pictures that diverged from his own standard by a large margin.

A4.2.27

A4.2.28 Workshop of Frans Hals, Fisherboy, c. 1636-1638

Oil on panel, 28.6 x 21.9 cm, monogrammed upper right: FH

Manchester, Manchester City Art Gallery, inv.no. 1979.460

The museum website lists this painting as made by the studio of Frans Hals.12 As in the other paintings of fisherchildren, the sketchy manner of execution indeed matches the coarse style of the Hals workshop. It was probably painted directly after a model or using a relevant sketch from the workshop stock.

A4.2.28

© Manchester City Art Gallery

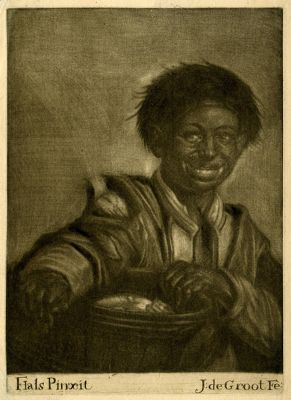

A4.2.29 Workshop or follower of Frans Hals, and Pieter de Molijn or his circle, Laughing fisherboy with a basket, c. 1636-1638

Oil on panel, 80 x 63.5 cm

Sale New York (Sotheby’s), 28 January 2005, lot 540

Overall, the manner of execution in this painting is somewhat flatter than that of the other half-length figures in dune landscapes. The figure has been rendered with wider, softer brushstrokes, and it is also known through a mezzotint by Johannes de Groot (c. 1688/89-after 1776) [1]. However, the print leaves out the landscape background, which is similar to that in the Fisherman playing the violin (A4.2.18). The motif of a ruined tower in a dune landscape can be found in several drawings by Pieter de Molijn (1595-1661), especially from 1653 and 1654.13 It is not known whether such models by Molijn already existed in the 1630s.

A4.2.29

1

Johannes de Groot (II)

Laughing Fisher Boy with a Basket, c. 1710-1720

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1874,0613.792

cat.no. C35

A4.2.29a Follower of Frans Hals, Laughing fisherboy with a basket

Oil on canvas, 80 x 64 cm

Sale London (Sotheby’s), 10 April 2013, lot 33 Christie's), 30 April 1954, lot 146

A4.2.29a

© Sotheby’s 2023

A4.2.29b Follower of Frans Hals, Laughing fisherboy

Oil on panel, 37.7 x 33.2 cm

Sale London (Sotheby’s), 1 July 2022, lot 130

A4.2.29b

© Sotheby’s 2023

A4.2.30 Workshop of Frans Hals, possibly Frans Hals (II), and Philips Wouwerman, Portrait of a fisherman holding a beer keg, c. 1636-1638

Oil on canvas, 82.9 x 68.5 cm

Sale New York (Sotheby’s), 1 February 2020, lot 191

Cornelis Guldewagen (1599-1663), who had his portrait painted by Hals between 1660 and 1663 (A4.3.54), was the owner of the brewery ‘t Vergulde Hart, respectively, Het Rode Hert.14 Such a red stag is emblazoned on the beer barrel held by the laughing man in this picture. I agree with Slive that the manner of execution of the figure is similar to that of the fisherboys in Antwerp (A4.2.20) and Dublin (A4.2.21).15 Nevertheless, I diverge from his opinion, in that I consider all three works to be workshop products.

While in autograph paintings by Hals, bold lines are used to denote different nuances of color and brightness, in this painting they are used in the contours of the face, clothes and hands. Such a brutalist touch as is displayed here, can be found nowhere else in Hals's oeuvre. The broad and sketchy brushstrokes are, however, close to the coarser hands that can be seen in the two family portraits in London (A4.3.19) and Madrid (A4.3.24). I would therefore assume that the same assistant who was employed in the execution of the family portraits, took even greater liberty in producing the present picture and the ones in Antwerp and Dublin. Hals himself could have laid out the composition, and, at the most, have prepared a sketch that formed the basis for the man’s face. Nevertheless, one needs to become accustomed to the idea that, in a workshop where the master created sensitive portraits, there could exist a second line of production for artworks executed in a broader manner, like the present painting. Once one has familiarized oneself to the idea that two such different styles coexisted within the same workshop, it becomes clear that the trees, sky and landscape were painted by a specialist who used the brush in a different way from the person who painted the figure of the man and his beer keg.

A4.2.30

Photograph Courtesy of Sotheby’s, Inc. © 2023

Notes

1 Stukenbrock 1993, p. 134; examination at the restoration department of the Wallraf-Richartz Museum from 30 July to 30 August 2018, museum’s internal documentation.

2 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 1, p. 142-143.

3 Stukenbrock 1993, p. 129-130.

4 Eisler 1977, p. 132-133.

5 Haarlem 1937, fig. 58. See also the RKD images record (no. 308074), in which the second image reflects the painting’s previous condition.

6 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 132.

7 Sale Amsterdam, 21 August 1799, lot 58 (Lugt 5966). See also: Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 132.

8 Sale London (Christie’s), 20 February 1920, lot 135.

9 Raleigh 1960, p. 136.

10 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 132.

11 Weller 2009, no. 19

12 https://manchesterartgallery.org/explore/title/?mag-object-8210 (accessed 3 April 2024).

13 For instance: Pieter de Molijn, Figures outside the ramparts of Brussels, near the Namense Poort, 1653, black chalk and grey wash on paper, 170 x 213 mm, sale Amsterdam (Christie’s), 9 November 1998, lot 73. Beck 1998, no. 206.

14 The Golden Stag, or the Red Stag. See: Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 44-45, 109; Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 35.

15 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, no. 71, 73, 74.