A4.2.7 - A4.2.11

A4.2.7 Workshop of Frans Hals, Boy with a lute and a wineglass, c. 1626-1628

Oil on canvas, 72.1 x 59.1 cm

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv.no. 14.40.604

This depiction is a demonstration: the empty glass, the sounds of the lute fading away, the sweet taste of the fruit on the table, and the rapidly passing youth of the merry protagonist all contribute to conveying the experience of transience. Hofrichter emphasized the moral message: ‘The subject of the painting is intemperance. The “fingernail-test” of the title is an allusion to the fact that the youth has drained his tankard to the point that not enough liquid is left to cover his fingernail'.1 In Hals’s realistic scene, the symbolic hints are not composed or read as rigid messages, but they are rather allusions to an underlying significance. In a perception focused on the appearance of the real world, vivid impressions simultaneously conveyed meaning.

If we want to know what viewers felt when looking at pictures, we need to compare typically ambiguous representations from the same period and region. There are two suitable examples for the present painting: one is the copper engraving by Theodor Matham (c. 1605-1676) from Haarlem, created in France in 1629 [1]. The other is a painting depicting the sense of taste [2], clearly influenced by Hals, from a series of the Five Senses by Petrus Staverenus (c. 1610-after 1654), also a member of the Haarlem guild of St Luke. The series was later distributed in print, for example by Abraham Bloteling (1640-1690)2 and Jan Verkolje (1650-1693).3 Both compositions address a wider public and depict sensory impressions as both comprehensible and transitory. The inscription under Matham’s engraving emphasizes this deeper experience:

‘All these rubies that we place

among the ranks of precious stones,

what if: we compared them

to these delicious drops:

which, as divine gifts, can

recall humans from their bones’.4

The boy in the present painting imitates the gesture of captain Michiel de Wael (1596-1659) in the Banquet of the officers of the St George civic guard of 1626-1627 (A1.30)[3]. The boy’s hand holding the glass is largely a copy, down to the shadow on the ring finger [4], even though the overall style of the brushwork is hesitant – noticeably also in the fingers and fingernails of the right hand, the hair and the central part of the face, as well as the cuffs and collar.5 In its type of model, and in the soft handling in the area around the eyes and mouth, the central part of the face ties in with Hals’s representations of merry musicians and may be based on a first design by Hals himself. However, the colors remain waxy, and the expression is comparatively rigid. I would not dare to propose an author for such a dependent work. It is possible that Judith Leyster (1609-1660) was the painter, as Hofrichter suggested, but it could equally be another assistant. In any case, the painting cannot have been painted prior to the 1626-1627 Banquet of the officers of the St George civic guard.

A4.2.7

1

Theodor Matham

Boy with a glass turned upside down, c. 1625-1629

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-2003-47

2

Petrus Staverenus

Personification of the five senses: Taste

© Christie’s Images Limited [2019]

3

Detail of cat.no. A1.130

Frans Hals (I)

Banquet of the officers of the St George civic guard, c. 1626-1627

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

4

Detail of cat.no. A4.2.7

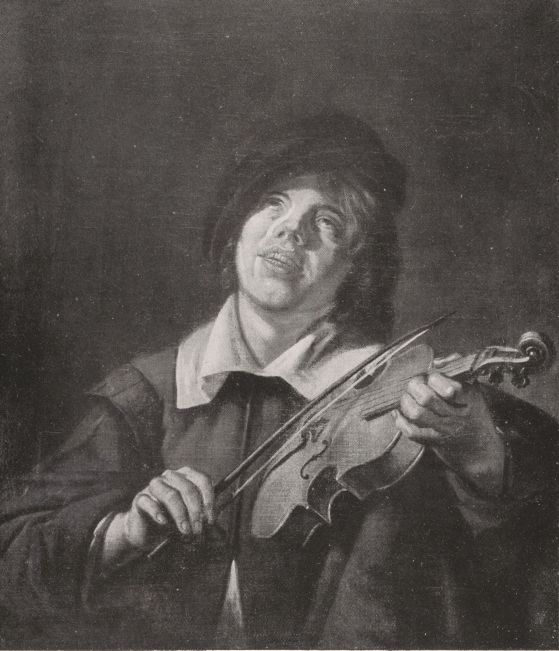

A4.2.8a Workshop of Frans Hals, possibly Jan Miense Molenaer or Judith Leyster, The violin player, c. 1626-1628

Oil on panel, 74.3 x 66.0 cm, monogrammed lower right: FH

Richmond, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, inv. no. 49.11.32

In 1964, Horst Gerson suggested an attribution to Judith Leyster (1609-1660), which was tentatively supported by Slive: ‘I tend to favor an attribution to Judith, and see a connection between it and the group of her paintings which, if not signed, would be attributed to the “Master of the Upward Glance”’ – pointing at the 1629 Serenade, the slightly later Two children with a cat and an eel and further examples.6 While I would also consider Leyster or perhaps Jan Miense Molenaer (c. 1610-1668) as the painter, the connection with the Hals workshop seems predominant to me. It is evident in many details, especially in the soft painterly design of the face and hands, which differs distinctly from depictions of figures playing the violin in Leyster’s late work. Hofrichter claims the picture for Leyster and refers to the FH monogram as ‘falsely inscribed’.7 However, there is no more evidence supporting this statement than for monograms in many other paintings that feature Hals's motifs in combination with execution styles that clearly deviate from his manner. On the contrary: the monogram – which is not suspicious, according to today’s technical examination criteria – is a document guiding the reconstruction of the collaboration between Leyster and Hals. If there are earlier works signed by Leyster, such as the Two children with a cat of 1629 (A4.2.10), that were described by engraver Cornelis Danckerts (1604-1656) as F. Hals pinxit (C15), there must have been special agreements between the master and his pupil. These must have taken into account the authorship of the design and the adopted templates, as well as an independent execution. Of equal importance was the introduction of the commission, which may also have been applicable for genre paintings. In the present case, the sense of hearing is represented according to the existing pictorial tradition of the Five Senses, while the diagonal composition and the transformation of the symbolical subject into an animated facial movement, are very close to Frans Hals. The boy’s model is possibly identical to that in the Boy with a lute and a wineglass (A4.2.7). The execution could be based on relevant facial studies by Hals. Hofrichter lists six different copies, all probably contemporary with the present painting, to which an additional variant can be added (A4.2.15).8

A4.2.8a

© Virginia Museum of Fine Arts / Photo: Troy Wilkinson

A4.2.8b Workshop of Frans Hals or possibly Judith Leyster, Young man playing the violin, c. 1626-1628

Oil on panel, 79 x 67 cm, monogrammed lower right: FH

Sale Vienna (Dorotheum), 9 April 2014, lot 787

A4.2.8b

© Dorotheum, Vienna

A4.2.8c Workshop or follower of Frans Hals, Young man playing the violin

Oil on canvas, 43 x 36 cm

Sale Amsterdam (Fr. Muller), 30 June- 2 July 1909, lot 12

A4.2.8c

A4.2.8d Workshop or follower of Frans Hals, Young man playing the violin

Oil on canvas, 87 x 74 cm

Sale Amsterdam (Roos), 31 March 1914, lot 39

A4.2.8d

A4.2.8e Workshop or follower of Frans Hals, Young man playing the violin

Oil on canvas, 75.5 x 63.5 cm

Vienna, art dealer Galerie Pallamar

A4.2.8e

A4.2.9 Workshop of Frans Hals – possibly Jan Miense Molenaer – and Pieter de Molijn, Young man playing the violin in a landscape, c. 1629

Oil on canvas, 100 x 83 cm

Ipswich (MA), private collection

This painting was first published by Hofrichter in 1989 and constitutes an extended variant of the Young man playing the violin (A4.2.8a), whilst stylistically deviating from it. The face has been smoothed and is reminiscent of faces in the early works of Jan Miense Molenaer (c. 1610-1668). Accordingly, the subject is especially closely related to Two boys and a girl making music, signed, and dated I MR 1629 [5]. That painting features a similarly positioned violinist, who also wears an open waistcoat, showing a long stretch of the white shirt underneath. It is more coherent overall and entirely consistent in the anatomy of the figures and their details. Consequently, it is only conceivable that it was created before, and not after the present picture. The latter has been assembled out of different motifs: the head imitating Hals, and the ‘Halsian’ hand – particularly the left hand, which copies Hals’ hand of Michiel de Wael (1596-1659) in the Banquet of the officers of the St George civic guard of 1626-1627 (A1.30)[3], and which was also used in Boy with a lute and a wineglass (A4.2.7). Such a connection with Hals’s templates and the references to a series of artworks produced in his workshop, suggest that the present painting might be a very early work by Molenaer, whose earliest dated paintings are from 1629. Finally, Young man playing the violin in a landscape may have been a commission that required an additional contribution by a landscape painter for the particularly attractive background, which, on the basis of stylistics, can be attributed to Pieter de Molijn (1595-1661).

A4.2.9

5

Jan Miense Molenaer

Two boys and a girl making music, dated 1629

London (England), National Gallery (London), inv./cat.nr. NG 5416

A4.2.10 Judith Leyster, Two children with a cat, c. 1629

Oil on canvas, 61 x 52 cm, signed and remains of a date lower left: JL* 16..

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. SK-C-1846

This painting can be connected to the other depictions of children created by the Hals workshop. The protagonist is based on the same model as the Laughing boy with a flute (compare: A4.2.3b).9 Yet, the present picture gives a much clearer idea of the gracefulness of the lost example by Hals, than the above-mentioned versions. At the same time, Leyster’s adoption of templates that were only accessible in the Hals workshop indicates her association with the workshop during the period of 1629-1630.

On the basis of the verse under the engraving of the present composition by Cornelis Danckerts (1604-1656) [6], Hofrichter interpreted the moral message of the scene as a reference to the ‘choleric inscrutability of cats’. The verse reads: ‘Tell him or me / if he who laughs / is happy / or hides no pain’.10 Interestingly, Danckerts referred to Frans Hals as the inventor of the composition, by including the inscription f. Hals pinxit to his print.

A4.2.10

6

Cornelis Danckerts (I)

Laughing boy and girl with cat and biscuit, after 1629

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1885-A-9027

cat.no. C15

A4.2.10a Judith Leyster, or her workshop, Boy with a cat

Oil on canvas, 77.5 x 50.5 cm

Sale Munich (Hampel), 19-20 September 2013, lot 597

A4.2.10a

© Hampel Fine Art Auctions

A4.2.11 Attributed to Judith Leyster, Merry company of three boys with a violin, c. 1629-1630

Oil on panel, 27.5 x 20.9 cm

Oslo, Nasjonalmuseet, inv.no. 1388

The present painting and the version of the Rommel-pot player in Chicago (A4.2.1r) are extremely closely related in their style of painting. The execution of the hair and the patchy light reflections in the faces are similar also to the to the monogrammed Two children with a cat (A4.2.10). Hofrichter notably recognized Adriaen Brouwer’s (c. 1605-1638) influence in the subject, the motifs and the free handling.11 From 1623 to c. 1626/1627 Brouwer was in Haarlem, where he presumably trained with Hals, according to Arnold Houbraken’s (1660-1719) biography.12 It is not clear how long this tutelage lasted and how close the collaboration was. There is certainly no workshop painting from the 1620s that could be stylistically attributed to Brouwer, or to Dirck van Delen (1605-1671), who probably trained in Hals’s workshop at the same time. Consequently, either some paintings by Brouwer remained in Hals’s workshop after he left, or the Chicago Rommel-pot player and the present picture should need to be detached from the attribution to Judith Leyster (1609-1660) and ascribed to the direct following of Brouwer, in which case they could not date later than 1626-1627.

A4.2.11

Notes

1 Hofrichter 1989, p. 58.

2 Abraham Bloteling, Man with an empty glass (Taste), mezzotint, 195 x 136 mm (plate edge), Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, inv. no. RP-P-1889-A-14494.

3 Jan Verkolje, Man with an empty glass (Taste), mezzotint, 163 x 122 mm (plate edge), Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, inv. no. RP-P-OB-17.543.

4 Tous ces Rubis que nous mettons / Aux rang des pierres pretieuses, / Quest-ce: si nous les comparons / A ces gouttes delicieuses: / Qui peuvent, comme dons devins, / Rappeler des mors les humains.

6 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 137. Judith Leyster, The serenade, 1629, oil on panel, 47 x 34.5 cm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. SK-A-2326; Two children with a cat and an eel, c. 1635, oil on panel, 59.6 x 48.2 cm, London, National Gallery, inv.no. NG5417.

7 Hofrichter 1989, p. 56.

8 Hofrichter 1989, p. 57.

10 ‘Seght my of hy, Die lacht is bly, /of weesens schyn verbercht geen pyn’. Hofrichter 1989, p. 45.

11 Hofrichter 1989, p. 44.

12 Houbraken 1718-1721, vol. 1, p. 319, 347.