C1 - C10

C1 Jan van de Velde, Portrait of Jacobus Hendricksz. Zaffius, 1630

Copper engraving, 264 x 177 mm, signed and dated lower right: J.V.Velde/ sculpsit anno/ 1630

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. RP-P-OB-15.269

Below the coat of arms is an inscription ÆTA: 84., corresponding to the sitter’s age when he died in 1618. Below the portrait, there is a Latin inscription, which reads:

‘Why is the likeness of Zaffius entrusted to fragile paper?

So that the man may outlive his ashes.

In truth, this face is the image of true Virtue,

Shining with intelligence and holy doctrine.

‘Simplicity’, wise Zaffius will say from his living lips,

Where thou seest here a form, true Faith sees God’.1

This engraving was probably created on the basis of a lost portrait from 1611, in which the chest and head sections were identical with the painted portrait of Jacobus Hendricksz. Zaffius (1534-1618) by Frans Hals [1]. Based on the coherence of the composition and the old-fashioned perspective, it seems unlikely that the modello for this print would date from shortly before it was created in 1630. The design of the hands also displays a Mannerist over-modelling, which conforms to the representation of the face in the painted bust-length portrait. There is every reason to assume that the engraving was based on an overall similar modello by Hals, that is, a three-quarter figure with a skull. Therefore, the print is included in the present publication as a document for this lost painting.

C1

1

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Jacobus Hendricksz. Zaffius, 1611

panel, oil paint, 54.5 x 41.2 cm

upper left: AETATIS SVAE/77 AN⁰ 1611

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. OS I-511

cat.no. A1.1

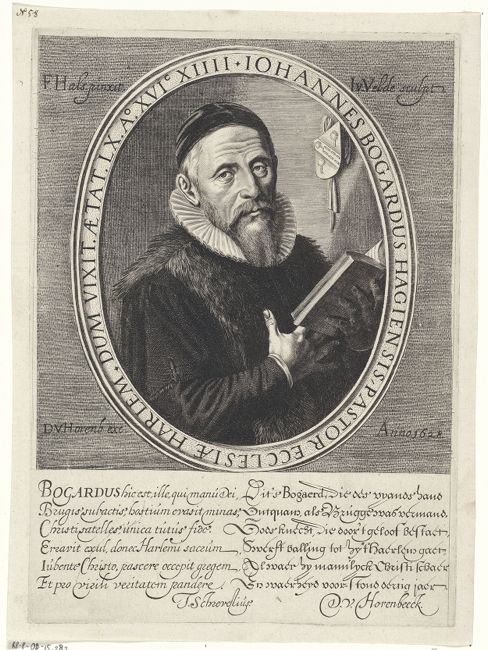

C2 Jan van de Velde, Portrait of Johannes Bogaert, 1628

Copper engraving, paper, 234 x 167 mm, signed upper right: I.v.Velde sculpt. Dated lower right: Anno 1628

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. RP-P-OB-15.282

Surrounding the portrait, the sitter’s name, age and year of death are inscribed in an oval frame. Beneath the portrait there is a poem in both Latin and Dutch:

‘This is Bogaerd, who by the hand of God,

escaped the enemy’s hand in Bruges.

Servant of God who exists through faith.

Wanders in exile until reaching Haarlem.

Where he spread His truth for thirty years’.2

Johannes Bogaert (1554-1614), born in The Hague, initially worked as a preacher in Bruges before being called to Haarlem in 1588, where he eventually died. Thus, his portrait must have been executed before 1614.3 With his deep-set eyes and a modelling based on the hard outlines of the facial features – the contours of nose, eyes and wrinkles in the forehead – the representation of the sitter’s face is close to that of Zaffius (A1.1). The hand with the wide-spread fingers under the book appears unusual, but is obscured by the book’s shadow.

C2

C3 Jacob Matham, Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius, 1618

Copper engraving, 262 x 160 mm, dated on the framing oval, lower centre: cIɔ. Iɔc. XVIII. Signed lower centre: Iac. Matham sculpsit.

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. RP-P-OB-27.290X

This print is a memorial for the ingenious scholar Theodorus Schrevelius (1572-1649), as well as for the superb engraver Jacob Matham (1571-1631). The latter implemented an entire pictorial programme into the elaborate ornamental border. The portrait was based on a lost template by Hals, which is documented through the small painted variant on copper in the Frans Hals Museum, dated 1617 [2]. Below the portrait, there is a poem written by Petrus Scriverius (1576-1660):

‘Because he bridled so many hard mouths of wayward youths,

With the force of his eloquence and his palladian discipline,

Schrevelius was worthy, Mathanius, of your copper,

Worthy too to win this reward for his conscientious care,

So that if perchance envious time should blot out his name

And hide the man, his likeness may speak for him’.4

C3

2

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius, 1617

copper, oil paint, 15.5 x 12 cm

center right: AET.44 /1617

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. OS-2003-18

cat.no. A4.1.1A

C4 Jonas Suyderhoef, Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius, c. 1642-1648

Copper engraving, 216 x 147 mm, signed lower right: I. Suyderhoef Scu.

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. RP-P-OB-60.762

This engraving of Theodorus Schrevelius (1572-1649) was executed after the painted and partly reworked copy on copper [2] and probably also on the basis of the print by Jacob Matham (1571-1631) (C3) – considering the identical inscriptions on the oval frame. The measurements of the portrait itself precisely match those of the small portrait on copper. The Latin text underneath the portrait was written by Caspar van Baerle (1584-1648), also known as Barlaeus. It reads as follows:

‘It were easy to portray this man when the stronger vigour of

His age and looks would themselves portray my Schrevelius.

Now it is harder to praise in his old age the man under whose championship

Frail savagery bowed its stiff head to Phoebus

Raw schoolboys were instructed in the arts of learning.

He who taught all how to live now lives for himself, and that

Tongue so elegant for Latinity is now silent.

Worn by his work as a schoolmaster, worn by so many labours,

His weary old age now beseeches Heaven for repose’.5

C4

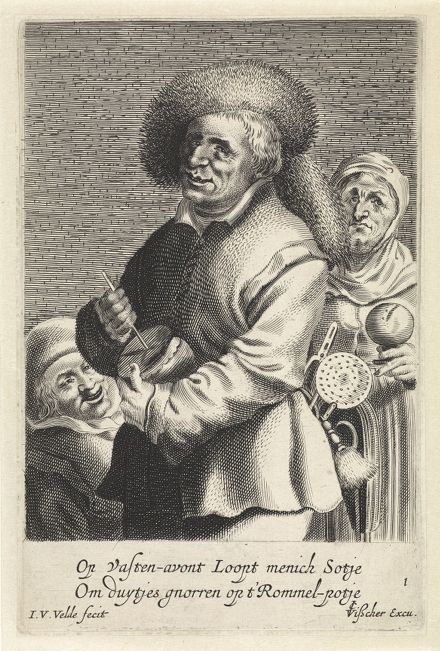

C5 Jan van de Velde, The rommel-pot player

Copper engraving, 203 x 134 mm, signed lower left: I. V. Velde fecit

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. RP-P-OB-15.301

The text under the picture reads as follows: ‘Many fools run around at Shrovetide / To make a half-penny grunt on a rommel-pot’.6 The protagonist is based on Hals’s figure of the Rommel-pot player [3], but with changed facial features and a different hat.

C5

3

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Rommel-pot player, c. 1622-1624

canvas, oil paint, 106 x 80.3 cm

Fort Worth, Kimbell Art Museum, inv.no. ACF 1951.01

cat.no. A4.2.1a

C6 Jan van Somer, The rommel-pot player

Mezzotint, 338 x 254 mm, signed lower right: j van Somer fecit

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. RP-P-1909-149

After one of the variants of the Rommel-pot player, featuring five children. The inscription lower left erroneously states that the example for the print was painted by Jan Lievens (1607-1674). Slive notes that the children’s costumes post-date 1650.7

C6

C7 François Hubert, The rommel-pot player, c. 1781-1783

Copper engraving, 238 x 198 mm, signed lower right: Hubert sculp.

The Hague, RKD - Netherlands Institute For Art History

This print was last published in Le Brun’s first volume of Galerie des peintres Flamands, Hollandais et Allemands of 1792. According to the accompanying text, the painting that served as the example, was at that time in the collection of Charles René Dominique Sochet Destouches (1727-1793). Slive published this engraving as an illustration of a no longer extant version of Hals’s composition.8

C7

C8 Pieter de Mare, The rommel-pot player

Copper engraving, 330 x 285 mm, signed lower right: P. de Mare Sc.

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. RP-P-OB-22.884

This engraving isolates the main protagonist and the boy on his immediate left from the entire crowd in Hals’s original composition [3]. This depiction is based on either the prime version by Hals, on one of the copies, or on an already existing variant featuring only these two figures. The contrast between the old man and the young boy, as well as the correspondence between their tilted heads are sufficient to illustrate the concept of ‘foolishness’. As in most of the 18th-century engravings made after works by Hals, the focus is on the entertainment value of the curious and grotesque figures. Slive pointed out that the fox tail was replaced by a bow in this instance, which eliminated the symbolical characterisation of the main protagonist as a fool.9

C8

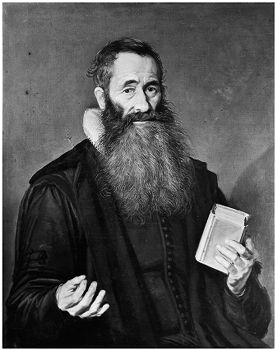

C9 Jan van de Velde, Portrait of Petrus Scriverius

Copper engraving, 267 x 155 mm, signed lower centre: I. v. velde sculpsit

London, The Royal Collection Trust, inv.no. 670167

After a lost modello by Frans Hals, which also served as the example for the painted portrait of Petrus Scriverius (1576-1660)[4]. The motto ‘LEGENDO ET SCRIBENDO’ on the oval frame around the portrait may be interpreted as delectatus sum, that is ‘I am delighted by reading and writing’, or alternatively ‘my life is dedicated to reading and writing’. As such, it resonates with the sitter’s name Scriverius, which is a Latinized version of his actual name Schrijver. The translation of the Latin inscription translates as follows:

‘You see here the face of one who, shunning public office,

Makes the Muses his own at his own expense.

He loves the privacy of his home, sells himself to none,

Devoting all his hours of leisure to his fellow-citizens.

While he castigates the faults and bland dreams of men of old,

He is also afire to win the esteem of you, his fellow Batavians.

Let gangs of workmen hired at great expense make a great din,

A free right-hand will produce sincere work’.10

The copper plate with the engraving has been preserved and is in the collection of the Stichting Familie van Hoogstraten in Dordrecht.

C9

© His Majesty King Charles III 2023

4

workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Petrus Scriverius, 1626

panel, oil paint, 22.2 x 16.5 cm

lower left: FHF

lower right: 1626

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv.no. 29.100.8

cat.no. A4.1.4

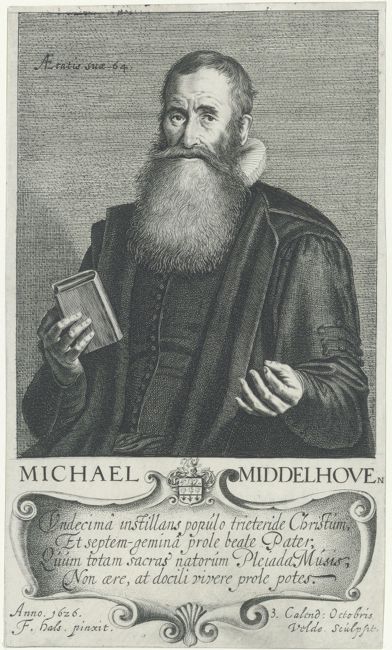

C10 Jan van de Velde, Portrait of Michiel Jansz van Middelhoven, 1626

Copper engraving, 210 x 125 mm, signed lower right: Velde. Sculpsit. Dated lower left and right: Anno. 16z6. 3. Calend: Octobris

Paris, Fondation Custodia- Collection Frits Lugt, inv.no. 3260

After the lost portrait by Frans Hals [5]. The text in the cartouche below the portrait reads as follows:

‘MICHAEL MIDDELHOVEn

Bringing Christ closer to his people over 33 years

And a happy father to 7 pairs of children

With this august pleiade of muses,

you cannot live on your stipend,

but through your learned descendants’.11

C10

5

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Michiel Jansz. van Middelhoven (1562-1638), 1626

Paris, private collection Adolphe Schloss

cat.no. A1.27

Notes

1 ‘Cur ZAFFI Teneræ mandatur imago papÿro’./Vt possit, cineri. VIR. superesse suo’./Scilicet hac facies veræ Virtutis imago est/Ingenio. sacris dogmatibusque. Nitens/Adspicis hanc.‘ PRVDENS, viventis ab ore. Loquetur/Simplicitas formam. Relligioque. Deum’.

2 ‘BOGARDUS hic est, ille, qui manu Dei, / Brugis subactis, hostium evasit minas; / Christi satelles, unica tutus fide. / Erravit exul, donec Harlemi sacrum, / Iubente Christo, pascere occepit gregem, / Et pro virili veritatem pandere. / T. Schrevelius’. Dutch: ‘Dit’s Bogaerd, die des vyands hand / Ontquam, als Brugge was vermand. / Gods knecht die door ’t geloof bestaet / Swerft balling tot hy t’Haerlem gaet / Alwaer hy mann’lyck Christi schaer / Zn waerheyd voor-Stond dertig jaer. / D.v. Hoornbeeck’.

3 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 120, no. L8. For further biographical information on Johannes Bogaert, see: Van der Aa 1852-1878, vol. 2-1, p. 767-768; Molhuysen 1911-1937, vol. 1, p. 384-385.

4 ‘Cum tot dura vagæ frenaverit ora iuventæ,/ Viribus eloquy, Palladijsque minis;/ Dignus erat Mathame tuo Schrevelius ære, / Dignus et hæc curæ præmia ferre’suæ. / Vt si fort’ætas obliteret invida nomen, / Dissimulet qu’ virum, posset imago loqui’.

5 ‘Tunc pinxisse virum, facile est; cum fortior ætas / Et frons Screevelivm pingeret ipsa meum. / Nunc laudasse senem, gravius. quo vindice, Phæbo / Barbaries rigidum subdidit agra caput. / Vivere qui cunctos docuit, sibi vivit, & illa, / In latias voces lingua discerta silet. / Quam trivere Scholæ, quam tot trivere labores, / Otia iam Superos fossa senecta rogat’.

6 ‘Op Vasten-avont Loopt menich Sotje / Om duytjes gnorren op t’ Rommel potje’.

7 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 118, no. L3-16.

8 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 118, no. L3-13.

9 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 118, no. L3-17.

10 ‘ILLIVS ORA VIDES, QVI PVBLICA MVNIA VITANS/ AONIAS PROPRIO VINDICAT AERE DEAS./ SECRETOSQUE LARES AMAT, HAVD MERCABILIS VLLI,/ CIVIBVS IMPENDENS OTIA TOTA SVIS,/ DVM VETERVM CVLPAS, BLANDITAQVE SOMNIA DAMNAT,/ ARDET ET IN LAVDES IRE BATAVE TVAS./ MAGNA CREPENT OPERAE MAGNIS MERCENDIBVS EMPTAE,/ LIBERA VERIDICVM DEXTERA PANGET OPVS’.

11 ‘MICHAEL MIDDELHOVEn/ Vndecima instillans populo trieteride Christum,/ Et septem-gemina prole beate Pater,/ Quum totam sacras natorum Pleiada Musis,/ Non aere, at docili vivere prole potes.’