5 The structure of the catalogue

Publications about early Netherlandish painting of the 15th and 16th centuries were the first to draw conclusions on pre-modern art production circumstances. They replaced the previous attribution of a master’s name with the group of hands that were involved, for example the ‘Van der Weyden group’, ‘Memling group’ etc., as has become widely accepted in titles and publications. The present catalogue thus lists all paintings by the ‘Hals group’, including those that were executed in part or entirely by the workshop, those that were most likely painted under the supervision of the master Frans Hals, sketched by him in greater or lesser detail, sometimes executed in part and reworked in sections by him, those that are legally signed with his monogram, and most probably sold by him. Previous studies of stylistic differences between different hands in Hals’s workshop are not invalidated by this approach, but take us closer to the context of historical production. They are duly taken into account in the present separate listing of works that are either entirely autograph, part autograph, or that were created by the workshop in the style of Hals. The comments for each item identify its autograph parts in order to facilitate critical reflection by the reader. When groups of paintings are probably attributable to individual workshop-assistants on the basis of typical stylistic features, these suggestions are also included.

The assumption of a workshop production turns many previous combinations on their head. It requires renewed detailed study of the entire historical tradition and leads to many reattributions. Therefore, the present catalogue comprises both the oeuvre considered as autograph in Slive’s catalogues, and the paintings he critically discussed and rejected, as well as a number of works not listed by him. Through the re-appearance of long-lost originals on the art market, through restorations, scientific-technical analysis and improved photographic documentation of previously known pictures, new distinctions between the traditional groups have become possible and necessary. New product lines are the result of a modified, more historical, approach. Groups of genre paintings such as the Rommel-pot player, some of the fisherchildren and musicians, but also some previously excluded portraits may not be imitations or variants of lost ‘originals’ by Hals, when they differ stylistically. Rather, one can assume a workshop- production based on more or less precise specifications by the master, and on designs possibly – but not necessarily – by his own hand. Generally, the experience of research into Rembrandt’s work also influences the understanding of paintings associated with Hals, since similarities and weaknesses may simply not be a result of later imitation, but occur in authentic pictures by workshop-assistants that may have been sold at lower prices.

With regard to a discussion of attributions, the most interesting group is the one under A3 in this catalogue, classified as made by Frans Hals and his workshop. Quite a few of these pictures display sections that are strikingly loose and at the same time very confidently done, and would only be attributable by comparative study to the virtuoso hand of Frans Hals himself. Their attribution used to be disputed, since the same paintings include weaker areas that are clearly executed by another hand. Typically, the facial features stand out; this is the case with the late Portrait of a woman in the Louvre [1], but even in the Portrait of Paulus van Beresteyn (A2.1) in the same collection, the quality in the area of the hands is far above that of the rest.

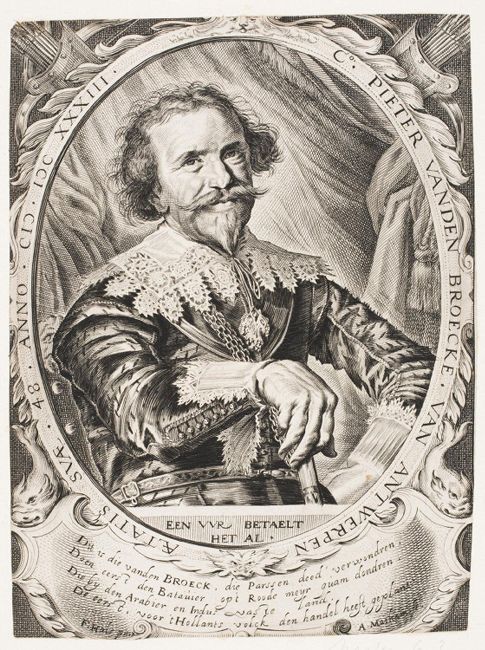

Following on from previous catalogue raisonnés, the present catalogue attempts to record the entire traditional oeuvre that can be considered as the output of Hals’s workshop. For that reason, it also includes exemplary copies and variants, engravings and drawings after lost paintings by Hals or his workshop. Contemporary engravings were also included in comparison with the surviving paintings. Digital photography allows unlimited enlargements, and enables a rediscovery of the almost unbelievable quality of engravings reproducing paintings by Hals. These were mostly created by the Haarlem masters Jacob (1571-1631), Adriaen (c. 1599-1660) and Theodor Matham (c. 1605/1606-1676), Jan van de Velde (1593-1641) and Jonas Suyderhoef (1614-1686), but also by Lucas Kilian (1579-1637) and others. In cases where the modello and the engraving could be juxtaposed, the quality can be verified immediately. If we want to gain an impression of the accuracy of representation and technical virtuosity in even minor nuances of light and shade, we need to read these engravings as serious professional documentation of lost model drawings or paintings. For this reason, contemporary engravings have been included in the present catalogue as important historical documents whose details can be compared to those of the paintings. Such a comparison can demonstrate general condition issues that lead to a loss in contrast, especially in the darker areas where white lead was only sparsely added to the paint for brightening and modelling. In other words: in Hals’s own time, many areas in a painting that were clearly defined in terms of detail and rendering of space, have since sunk into the general darker background shade. Numerous engravings allow tracking of this process, for example Adriaen Matham’s reproduction of the portrait of Pieter van den Broecke [2][3], as well as many others. Equally, there were fine details in the paintings that were lost in later cleaning and filling, but which retain a convincing presence in the engravings. This documentary value of prints, even in cases where the original is preserved, has prompted me to include the contemporary engravings after Hals’s paintings in their entirety. There are two further aspects of documentary value. The inscriptions are distinctly preserved and complement the inscriptions in paintings and related documentation, that may sometimes be lost, incomplete, or overall paltry. In addition, the wording that is often added below the depiction can supply instructive historical information as well as a reflection of the contemporary expectations of portraits.

Any differentiation between ‘master’ and ‘workshop’ which is founded on judgments of ‘quality’ and ‘style’ will inevitably include subjective criteria. All attributions rely on impressions and correlations that need to be constantly checked and rechecked, especially in comparison with available photographic material. To move forward, comprehensive and current reproduction material needs to be used, which allows previously hidden qualities to become visible. Already, colour photography and improved printing quality have increased the possibilities to objectify observations over the last decades. Digital photography offers even greater precision and much wider accessibility. Hopefully very soon, all museum collections will be accessible via the internet in high-resolution digital images. At that point, any findings from comparisons can then be held against traditional interpretations, down to the craquelure.

A1 Paintings by Frans Hals, or which have been reworked by him throughout

This group comprises the core of the generally accepted paintings that display the marks of the individual execution by Frans Hals throughout, as far as recognizable. Borderline cases are the pictures with limited background areas that can be by Hals or other people, as well as those with later overpainting or restorations covering an originally autograph paint layer. As in some group paintings, there are borderline cases with parts painted by assistants based on Hals’s design and then reworked by himself. This qualification also applies to some paintings under A2.

The discussion of individual works listed under categories A1 to A4 is followed by lists of copies that are still extant today, or which are referenced to in the literature. Many of these were at some point put forward as Hals-originals, which needs clarifying. They are listed in the present publication under the same catalogue numbers as the original models, qualified by letters in alphabetical order.

A2 Paintings by Frans Hals, with contributions by other masters or workshops

This group is also part of the core collection of verified works by Hals. Within it, paintings that have contributions by other fellow painters beside Hals are set apart. This is mainly the case with regard to the landscape backgrounds. These paintings have been taken out of category A1 in order to illustrate an extensive practice of cooperation in the production of pictures in a mostly artisanal context. Detailed photographs permit the documentation of a surprising range of cooperation and later additions. These include a composition by another hand with a figure by Hals inserted (A2.9), as well as insertions by third parties in Hals’s own compositions (A2.3). Even prominent areas like heads, collars and hands, which would fall under Hals’s own competence, were sometimes executed by other painters. The largest part of such cooperation is, however, listed in the category A3.

A3 Paintings with discernible stylistic differences in separate areas, comprising both sections that were recognizably painted by Frans Hals, and contributions by workshop-assistants

Works from all periods in Hals’s oeuvre show stylistic and qualitative variations between individual sections. With this master, the study of more or less close correlations between similar motifs – for example the dress or the hands – by Hals gives a very clear idea of his approach. The reason is the remarkable homogeneity of what has been preserved, while virtuoso brushwork is combined with distinct anatomical understanding. Recognizing this typical mode of representation permits to differentiate between areas that were probably executed by the master himself and those that were carried out by another hand. Above all, differences can be discerned in Hals’s specific ability of focusing on the visual appearance in the observation of physical qualities. This is especially noticeable in the psychology of momentary observation.

There is usually a less developed ability to capture optical phenomena in the contributions by assistants, but also a reduced psychology in the momentary observation. Contributions by assistants are therefore quite easily recognizable, as they have not sufficiently absorbed Hals’s probably mostly unconscious approach. While partial divergences or weaknesses were previously used to argue against authentication of entire works by the master, or at least to express doubt, the historically founded assumption of a workshop practice can reach to a more satisfactory and more acceptable solution while taking the actual appearance of many works into account. From a historical point of view, even those artworks with only a partially autograph involvement are by Frans Hals, as they were created under his supervision, and he was the recipient for commission payments. From the point of view of having been executed by his own hand, they are however only partially attributable.

A4 Paintings that were executed under Hals’s supervision, probably on the basis of his compositional designs and using his templates

Many paintings that are similar to Hals’s secure autograph works, yet which differ from them in typical elements have been attributed to him in the past, on the basis of historical documentation, inscriptions on contemporary reproductive prints, the association between pendants, credible historical signatures, as well as subject matter and style. There is the phenomenon of the sketchy Frans Hals style that is recognizable at different levels of quality and based on various originals from different creative periods. This ‘Halsian’ characteristic can also be found in areas and artworks which can certainly not be considered autograph. In the historical sense, all these paintings and areas of paintings are by Frans Hals, as they were most likely executed under his supervision in the workshop, and largely following his intentions, even though not touched by his own hand. In many cases, an underdrawing or a first sketch may have formed the basis for the paint layer that was applied by assistants. It must be assumed that the composition and the principal design of these creations were in keeping with the ideas of Frans Hals, respectively with the contemporary assessment and the asking price for such products by his workshop. Many of these artworks bear a historical signature, in the sense that it was applied at the time when they were painted. This is particularly true for the genre paintings.

A4.1 Miniature portraits and portraits executed parallel to engraved portraits

This section combines small-scale portraits that can be identified on the basis of engravings, with smaller portrait-formats from the Hals workshop that are similar in type. With regard to all ambitious painting commissions, from today's perspective, we would like to assume that Hals created at least the basic design himself. This also applies to the small surviving portraits. Their function as modellos for prints does not seem coincidental, as they were probably made for the express purpose of an engraving. However, with the exception of the Portrait of Jean de la Chambre (A1.87), which shows Hals's brushwork throughout, the smaller pictures are stylistically different from Hals's autograph works and display significant weaknesses in execution. For a long time, I was convinced that these were copies after lost originals. But why should the majority of portraits of prominent personalities at the time have been lost? Their portrait engravings were commissioned by institutions such as churches, schools and universities; they safeguarded these testimonials of their own tradition in the same way as they did paintings. Accordingly, it was rather more likely that these would survive. An explanation for the loss of quality in the small-scale oil paintings can be found in the assumption that Hals would only very rarely produce a complete oil painting in preparation for an engraving. After all, the main purpose of these commissions was the print and not the painted portrait. This is underlined by the wording of contemporary inscriptions illustrating the importance of the respective sitter. The production of an oil painting was an additional cost factor, which a painter only accepted once a commission was given. What we regard as cheap supports today, was valuable material for Frans Hals, consisting of imported oak, copper or primed canvas on stretchers. Such material costs are listed separately in many invoices from the 17th century.

The process of paintings production can be imagined as follows: a scholar working for a distinguished school – or, equally, a professor at a university or a clergyman serving a community – would usually have his portrait painted as a commission by the school, or on the initiative of the engraver or publisher who would be able to sell the prints to interested clients. Wealthy private scholars such as Theodorus Schrevelius (1572-1649), Petrus Scriverius (1576-1660) or the three calligraphers Arnold Möller, Jean de la Chambre (1605/1606-1668), and Theodorus Blevet (1598-1661) were the exception. These sitters commissioned Hals to create their portrait painting as a modello for the engraving, in order to send the prints with its inscribed eulogy to a circle of recipients. Schrevelius, Scriverius and possibly also Blevet added the painted portraits of their wives to their own, matching in size, and probably to hang in their homes. Unless a specific commission had been given for a painted portrait, a painter had no reason to bear the material costs and effort for such a work. A modello of the sitter in oil on paper would then suffice. This execution also did not have to present a complete painting, but could be limited to the crucial part of the face. The rest could be worked out by assistants.

One such surviving example painted on paper is the Portrait of Theodor Wickenburg (A4.1.17), which was still listed in 1923, yet has since been lost.1 Paper permitted an easy transfer of a design to an engraver's copperplate as well as other substrates; it is ideal for repeated use, as is illustrated by the matching sizes of engravings and paintings. However, the painted paper would become worn, and was not very durable anyway. ‘Like other seventeenth-century artists – most notably Rembrandt, Van Goyen and his brother Dirck – Frans Hals may have occasionally sketched in oil on paper. These works are conspicuously rare today because with age paper becomes a brittle support for oil paint. If Hals made any they may have simply disintegrated’.2 I consider these observations fundamental, also with regard to modellos for the group portraits. The oil paintings that often, but not always, matched the size of the engravings, were in many cases a parallel safeguarding measure, based on the modello delivered to the engraver. Therefore, neither the portrait of René Descartes (A4.1.15, A4.1.15a) nor those of the Haarlem scholars and theologians must have been created as original paintings on panel or canvas. In addition, Hals's painted modello may sometimes have consisted only of a head. The workshop assistants would then have completed the remainder of the composition in accordance with general instructions. A key example for this practice is the Portrait of Isaac Abrahsmz. Massa, dated 1635 (A4.1.11), which shows lines of copying points along the mouth and eyes.3 This means that the initial depiction of the face was used for both the engraving and the preserved painting. Without question, the engraving shows qualities which cannot be found with the same clarity in the painted portrait.

The discussion whether these and other small-scale portraits are copies or originals can only be conducted on the basis of critical comparison of preserved objects and consideration of historical production procedure. In this context, connoisseurship is irreplaceable. There is no ‘technical evidence’ confirming or denying the authorship of a particular master, as is sometimes stated.4 No technical examination can distinguish the hand of the master from that of an assistant in the same workshop, or of a collaborator working with the same material and in the same process.

A4.2 Genre paintings and A4.3 Portraits

Where Hals’s assistants were granted the greatest flexibility was in portrait-like genre paintings. These similarly sized depictions of figures that were laughing, singing, drinking or playing music, represent a production for the open market – in contrast to commissioned portraits. It seems likely that different levels of execution quality commanded different levels of pricing. In addition, there is a considerable range in the quality of the paintings. There is no documentation about the extent to which the master gave his assistants instructions, and it is not evident from the works either. Within Hals’s workshop, there are different stylistic types. Historically, all these artworks are originals by Hals; with regard to research into his individual powers of expression and their development they are products of his supervision. Yet, even within the products from the Hals workshop, individual artistic achievements are recognizable – ranging from the New York Malle Babbe (A4.2.31), to the late male portrait in the Fitzwilliam Museum (A4.3.55). However, we can only tentatively put a name to these. Only the signed works by Jan Hals (I) form a distinct group, together with very closely related paintings. These have been included in the present catalogue, even though it is not certain if they were actually executed within Hals’s workshop or elsewhere.

B Documentary workshop replicas, copies and variations

Several paintings by Hals are only documented through repetitions. Where there are several of these that are all based on the same composition, those that are closest to the date of creation and most reliable have been listed first. Furthermore, this section includes documentary partial repetitions and variants that reflect an original execution by Hals which does not survive accordingly in the preserved originals. These comparative examples serve the purpose of clarifying Hals’s subject matter and the understanding of his workshop practices, including the making of copies and variants.

C Documentary engravings

Engravings after works by Hals can be divided into two main groups: contemporary and later reproductions. The first were purpose-driven, probably initiated by the painter or patron themselves in the majority of cases, and approved by them. These are portraits that commemorate esteemed priests, scholars and artists. In addition, there are amusing and entertaining representations of quirky individuals such as Verdonck and Peeckelhaering, who had aroused public interest, as well as a few moralising genre scenes.

The second group contains works not envisaged by the artist, and consists of mostly much later reproductions of his paintings as examples of special representational quality. Other than Rembrandt (1606-1669), who often captured and distributed his own pictorial creations in engravings, Hals became known to a wider public only through engravings created after his work by other hands. Only a small part of Hals's public before the 19th century consisted of collectors of paintings and prints. The major part was composed of relatives, friends, admirers and followers of the people represented by Hals, as well as enthusiasts of bizarre expressive characters. Their interest was mainly directed towards the representation, while their interest in Hals's artisticity was limited. Admittedly, the engravings only hinted at his virtuoso ability.

The remaining engravings can provide a detailed impression of Hals's creation of artworks that are no longer extant. But in many cases they can also record earlier states of preservation of paintings and qualities no longer visible in the pictures. The innovative general accessibility of engravings through online databases – such as RKD images, Graphikportal, the British Museum’s Collection Online, the Rijksmuseum’s Rijksstudio, and the online collection of the Fitzwilliam Museum – and the increasingly high-resolution of the images allow informative observations and comparisons. Accordingly, the 17th- and 18th-century engravings after works by Hals and his workshop have been included in the present catalogue in full, following the chronological sequence of Hals's models.

D Paintings, drawings and watercolours as documentary copies

Sometimes, only a drawing after a painting survives as documentation of the original composition. Sizes have often been changed and compositions reduced or altered. Occasionally, the original appearance of formerly brighter and more contrasting colors can also be glimpsed in such drawings and watercolour copies, especially with regard to dark shades and the design of the background.

E Attributions

This group consists of problematic cases among the preserved paintings, as long as these are still relevant for Hals-research or have become topical through recent findings and exhibitions. Previous suggestions for attributions from different sources are listed, as well as alternative proposals, the relevant literature references to the discussion are listed in the accompanying records in RKD images.

X Imitations

In the 17th and 18th centuries, copies and variations of Hals’s paintings were created, with the focus primarily on the subject matter and compositional innovation. It was only the discovery of Hals's style of painting as ‘Art’ in the modern sense – and the high prices that this type of paintings fetched – that led to the creation of free imitations by modern masters. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when Hals was admired by Realists, Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, many artworks were created that are now easily recognizable as forgeries and that can be verified as such because of their material characteristics. With very few exceptions, these are not included in the present catalogue, apart from those that are present in museum collections or the art historical literature about Hals as autograph works, or at least have been seriously considered as such.

1

Frans Hals (I) and Jan Hals (I)

Portrait of a woman

canvas, oil paint, 108 x 80 cm

Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv.no. MI 927

© 2011 RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Franck Raux

cat.no. A3.53

2

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Pieter van den Broecke (1585-1640), 1633

Hampstead (Greater London), Kenwood The Iveagh Bequest, inv./cat.nr. 51 (88028830)

cat.no. A1.58

© Historic England Archive. Reuse not permitted

3

Adriaen Matham

Portrait of Pieter van den Broecke (1585-1640), dated 1633

Philadelphia (Pennsylvania), Philadelphia Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 1985-52-34432

cat.no. C24

Notes

1 Valentiner 1923, p. 270.

2 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 125.

3 The linear composition of the subject was copied from a modello. Small black dots are recognizable on the outer contours of the lips, the lines of the eyes, eyelids, eyebrows and moustache hairs, resembling a string of pearls. These are traces of the black powder coming through pinprick holes in a drawing on paper or parchment. The traces of this method, which had been used since the Middle Ages, were not obliterated by the partly thin paint layer and remained visible through the dry paint.

4 In the context discussed here, see: Liedtke 2007, vol. 1, p. 283.