A4.1.1 - A4.1.5

A4.1.1 Workshop of Frans Hals, Portrait of a man holding a lute, c. 1620

Oil on copper, 10.8 x 8.3 cm

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut, inv. no. 1998.15.1

The style of painting and the clothing of the sitter indicate a date around 1620. The execution is smoother than that of confirmed works by Hals. The facial features resemble the sitter in the portrait of 1619 in Dijon (A1.8). The likeness was copied in drawings by Tako Hajo Jelgersma (c. 1717-1795), in the Teylers Museum in Haarlem (D74), and Pieter de Goeje (1789-1859) in the University Library in Leiden (D73). Van Hall assumed a painting by Frans Hals as a modello.1

A4.1.1

The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund

© Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford CT / Photo: Allen Phillips

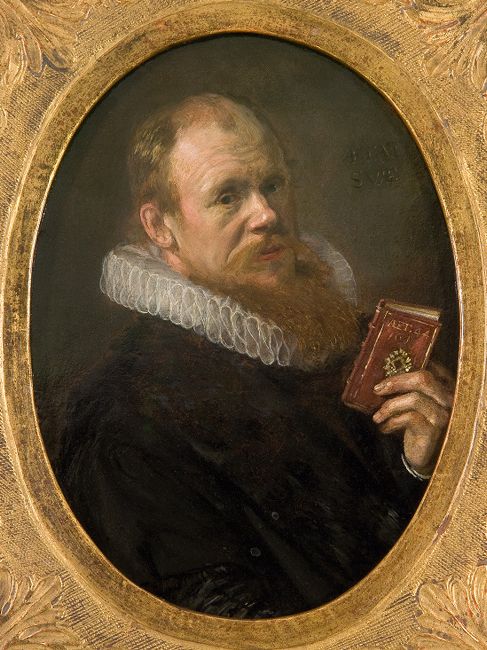

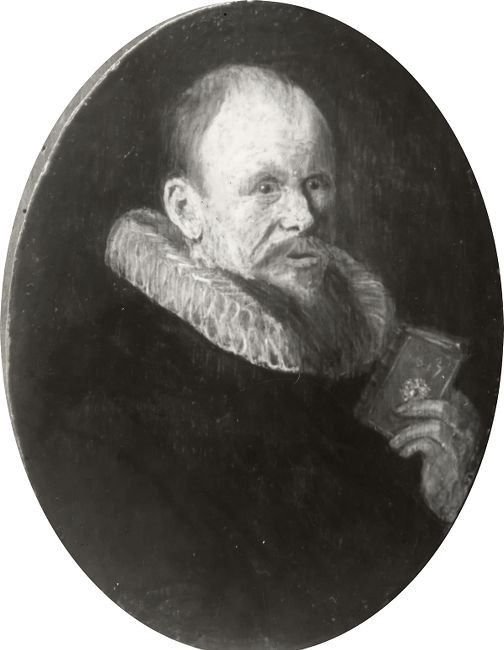

A4.1.1A Workshop of Frans Hals, Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius, 1617

Oil on copper, 15.5 x 12 cm, inscribed and dated center right: AET.44 / 1617

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv. no. OS 2003-18

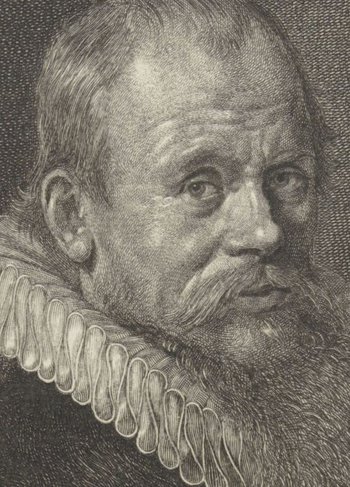

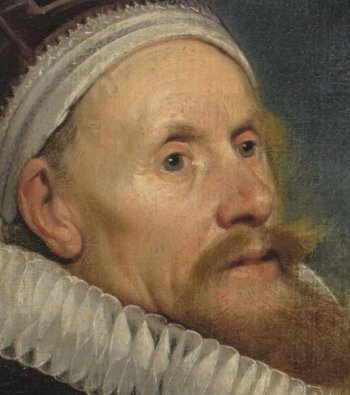

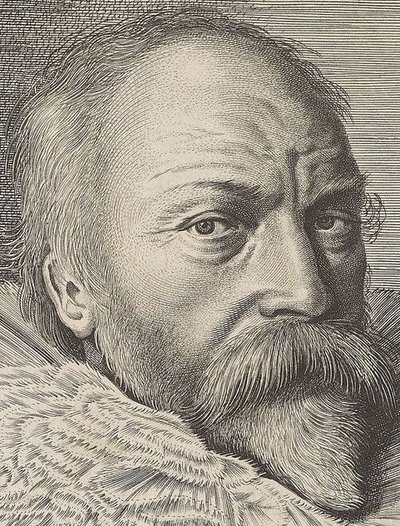

The present painting was the subject of several controversial assessments, both with regard to its quality of execution and its placement in the oeuvre of Frans Hals. As far as today’s condition allows to see, Hals’s typical brushwork is preserved intact only in the area below the collar in the left half of the composition, while the original paint in the central area of the head can only be gleaned. The portrait was disfigured by damages and paint losses. The differences with the original state become apparent in comparison with two contemporary copper engravings of exactly the same size, which represent the subject in reverse. The first is by Jacob Matham (1571-1631), dated 1618 (C3) [1], and the second by Jonas Suyderhoef (1614-1686), probably created between 1642 and 1648 (C4) [2]. Both refer to Frans Hals as the painter of the modello, yet there are such significant differences between them, that it is likely they were based on different examples. In Matham’s representation, the proportions of the face are more elongated – higher forehead, narrow ear with a thicker upper rim, longer nose, shorter distance between the nose and mouth, subtle modelling of forehead, eyes, and cheeks. The engraving by Suyderhoef, then again, displays a different direction of the eyes. And only in this print, we see the blinking left eye and the smug expression in the area of the mouth and nose, the slightly raised eyebrows and the separately depicted wrinkles in the forehead. In proportions, this later print is more consistent with the painted likeness of Schrevelius, even though the surface of the painting has abraded strongly.

Up to now, it was predominantly believed that Hals created this small oval portrait, which in turn served as the example for the engravings by Matham and Suyderhoef.2 After all, we find references to him on both prints. Additionally, there is a contemporary document that mentions a portrait of Schrevelius, painted by Hals. In his diary, the humanist Aernout van Buchel (1565-1641) mentions a visit to Schrevelius in Leiden on 10 January 1628. On this occasion, he was shown the latter’s portrait that was painted by Hals. Buchelius writes: ‘Rector Schrevelius also showed his portrait by Hals, the Haarlem painter, on a small panel, painted most vividly’.3 The painting must have appeared differently than it does now: fresher and with many original details still present. Accordingly, Martin Bijl writes that ‘Matham made his reproduction in 1617 or 1618 after a significantly lighter painting’.4 However, Valentiner already expressed the idea that Matham’s print was actually not created on the basis of the painting.5 Following the differences between the two engravings, he supposed that Matham must have used an example by his father-in-law Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617). But in this case, the Mannerist character of Matham’s print is brought forth by the engraver’s own typical elegant lines which do not necessarily have to trace back to a template by Goltzius. Finally, we have the clear indication on the engraving itself: ‘Fra Hals pinxit’.

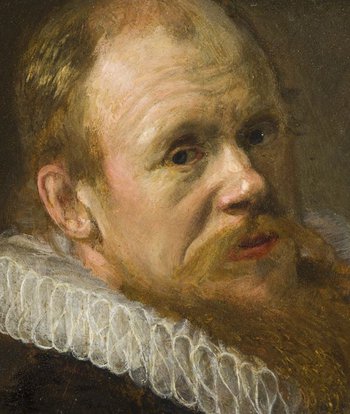

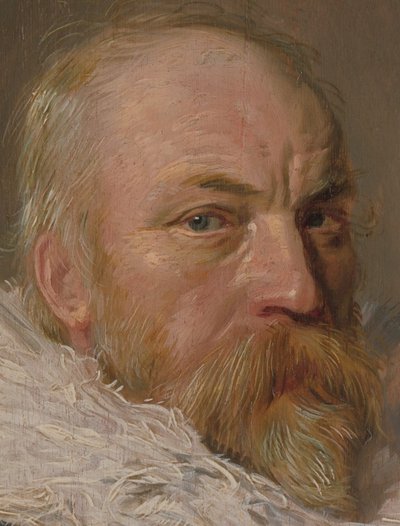

The conclusion that can be drawn today, after precise comparison of the currently available photographs, is that a model painted by Hals must have existed prior to the engraving of Matham, which the latter has meticulously reproduced. In its facial proportions and colorful appearance, this original was probably close to the portrait of Schrevelius that is included in the family portrait by Pieter de Grebber (c. 1600-1652), created in 1625 [3].6 When Schrevelius or his friends planned to produce another edition of portrait prints 30 years after the creation of the Matham print, Hals’s original example was probably no longer available. Most likely, it had been executed on paper, or it consisted of multiple studies that were not intended to be preserved. However, a version of the same format in oil on copper – this material was used for the majority of the small formats created in Hals’s workshop – had been produced as a ricordo, which is the painting under discussion here [4]. This workshop product was probably in the possession of Schrevelius, together with the – now lost – portrait of Maria van Teylingen, which served as its counterpart.7 Comparison shows that this painted repetition differs from the 1618 engraving in small details.

After Matham had died in 1631, and Suyderhoef had been successfully producing portrait engravings for Hals since 1637, the latter also took on the creation of the new Schrevelius print in the 1640s. The example for this engraving seems to have been only the painted copper plate discussed here, albeit with fresh revisions, such as the highlights on the nose, which Bijl identified as compressed patches of paint that had not yet fully dried.8 Further modifications concerned the mischievously mocking facial expression, with the eyes turned towards the viewer, which does not appear like this in Matham’s 1618 print. Who carried out these alterations cannot be determined. Unfortunately, these early revisions in the painting fell victim to later cleaning and reworking and are no longer preserved. Suyderhoef’s engraving thus shows them as a snapshot from the past. This difference in direct source of inspiration makes the print by Matham the only surviving document for Hals’s original, no longer extant, painted portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius. That this must have been a highly detailed work of art, is witnessed by the detailing in the costume. The curved surfaces of the various fabrics and fur have been rendered virtuously, despite the small format. Comparing these details in the Matham print with the painted version, provides us with a clear order between the variants: it is possible to paint the costume as a simplified and inaccurate version on the basis of Matham’s engraved example [5][6]. It is, however, impossible to develop such a coherent representation of forms, surfaces, and illumination when using the coarsely painted portrait as the point of departure. The Suyderhoef print, in turn, illustrates what comes out when one creates an engraving on the basis of such an example [7].

The sitter in this portrait, Theodorus Schrevelius (1572-1649), son of the cabinetmaker Cornelis Jansz Schrevel, was the director of the Latin school in Haarlem when Hals painted him in 1617. This municipal Latin school, which still exists today, has been founded in 1389, making it one of the oldest of its kind in Europe. Later on, from 1625 to 1642, Schrevelius served as rector of the Latin school in Leiden. He is the author of a history of Haarlem, published in 1647. In this publication one finds a praising passage about the paintings of Frans Hals, which is the most detailed account of his work that was written by a contemporary. Literally, it reads that Hals ‘[...] excels almost everyone with the superb and uncommon manner of painting, which is uniquely his. His paintings are imbued with such force and vitality that he seems to defy nature herself with his brush. This is seen in all his portraits, so numerous as to pass belief, which are colored in such a way that they seem to live and breathe’.9 This appreciation is, however, only relative. It corresponds in tone and length to the similar words of praise that Schrevelius wrote about Hals’s Haarlem colleagues. It should also be mentioned that in 1625, some years after Hals made his portrait, Schrevelius commissioned another, more ambitious portrait of him and his family not from Hals, but from his younger Haarlem colleague Pieter de Grebber. Unfortunately, it remains unclear what prompted Hals’s portrait of Schrevelius and who might have commissioned it. The text underneath Matham’s engraving gives a possible explanation. Referring to Schrevelius’s position as a schoolmaster, it reads: ‘Because he bridled so many hard mouths of wayward youths,/ With the force of his eloquence and his Palladian discipline,/ Schrevelius was worthy, Mathanius, of your copper […]’.10 Remarkable is also the emphasis on the skill of the engraver – which was probably the primary concern – instead of Hals’s achievement in creating the painted likeness of Schrevelius. Between 1607 and 1618, Schrevelius served in the city council of Haarlem. He had to give up this post because of the conflicts between the orthodox Calvinists and the more liberal Remonstrants, to which he belonged himself. In 1620 he also lost his position at the Latin school, which prompted him to move to Leiden. Confessional conflicts had probably been looming in Haarlem for some time, and it is thus plausible that Schrevelius planned his portrait in 1617 either as an advertisement of his services, or, resignedly, as a token of gratitude to his supporters. The production of the portrait engraving would then have been the decisive motive to have his portrait painted, and Schrevelius himself would have been the patron. The existence of a painted companion piece also supports this hypothesis.11

A4.1.1A

1

Detail of cat.no. C3, reversed

Jacob Matham

Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius, 1618

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

2

Detail of cat.no. C4, reversed

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius, c. 1642-1648

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

3

Detail of: Pieter de Grebber

Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius and his family, 1625

Amsterdam Museum

4

Detail of cat.no. A4.1.1

5

Detail of fig. cat.no. A4.1.1

6

Detail of cat.no. C3, reversed

Jacob Matham

Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius, 1618

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

7

Detail of cat.no. C4, reversed

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius, c. 1642-1648

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

A4.1.1Aa Anonymous, Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius

Oil on panel, 14.5 x 10.8 cm

Dublin, private collection

This bust-length portrait appears nearly identical in size to the one on copper (A4.1.1A). Overall, the execution appears coarser, yet it was more likely based on the painted portrait than on the engraving by Suyderhoef (C4).

A4.1.1Aa

A4.1.2 Workshop of Frans Hals, Portrait of a young cavalier, 1624

Oil on copper, 21.6 x 14.3 cm, inscribed and dated upper right: AETAT:SUAE 24 / Ao 1624.

Frankfurt am Main, Städel Museum, inv.no. 292

If we assume the existence of a workshop practice in which different levels of involvement by the master can be discerned, there is no longer any reason to regard the present painting – or many other ‘Halsian’ portraits – as a copy after a lost original.12 The present small-scale painting was most likely created by an assistant, on the basis of a design by Hals, adopting a conventional posture. While the execution of the hands and the clothing appears smooth and hesitant, and the man’s right hand was foreshortened clumsily, the face is modelled in a more confident manner. Nevertheless, the rendering of details such as the ear, the hairline, and the area around the eyes, does not show Hals’s clear brushwork. The same is true for the lighter spots and highlights on the nose, eye, and mouth. These are correctly set in their brightness, while deviating from Hals’s style. Such an appearance would suggest an execution based on a separate study of the head, rather than the involvement of the master in this portrait.

Until a few years ago, it seemed plausible to me to identify the sitter as Adriaen Matham (c. 1599-1660), who is depicted as an ensign in the Banquet of the officers of the Calivermen civic guard (A2.8A).13 The indication of the sitter's age on the present portrait would correspond. However, comparing new, high-quality photographs of both paintings, has revealed clear differences [8][9]. In contrast to the brown eye-color of the man in the present painting, Adriaen Matham in the group portrait has blue-grey eyes. Additionally, the distance between the nostril and the eyelid is larger there, and the shape of the ear lobe differs. Following this observation, I agree with Neumeister, who in her catalog of the Dutch paintings of the Städel Museum, speaks of an unidentified sitter.14

A4.1.2

8

Detail of cat.no. A4.1.2

9

Detail of cat.no. A2.8A

Frans Hals (I)

Banquet of the officers of the Calivermen civic guard

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

A4.1.3 Workshop of Frans Hals, Portrait of a man, c. 1625

Oil on copper, 12.4 x 9.7 cm

The Kremer Collection

The soft modelling of the face, with only a few accents, does not conform to Hals’s autograph style, and neither do the small dashes that are used for rendering the collar and sleeve . However, it is conceivable that there was a lost original or a preparatory study by Hals that served as the example for this characteristic, somewhat puffy face, with its humorous twinkle.

A4.1.3

A4.1.4 Workshop of Frans Hals, Portrait of Petrus Scriverius, 1626

Oil on panel, 22.2 x 16.5 cm, monogrammed lower left FHF; dated lower right 1626

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv. no. 29.100.8

Pendant to A4.1.5

A4.1.4

A4.1.5

The sitter was born in Haarlem as Pieter Schrijver (1576-1660), and later Latinized his name to Petrus Scriverius. He studied in Leiden, where he later worked as a poet and historian. He was well-acquainted to Theodorus Schrevelius (1572-1649), for whose portrait engraving of 1618 (C3) he created the accompanying poem of praise.15 He is also mentioned in the diary of the Utrecht lawyer Aernout van Buchel (1565-1641), whom Schrevelius had gifted a portrait engraving of Scriverius. This engraving by Jan van de Velde (1593-1641) is dated 1626 and measures 26.8 x 15.6 cm [10]. The oval in which the sitter is positioned in the print, is exactly the same size as that in the present painting.

In the art historical literature – most recently Walter Liedtke’s publications – the painting is energetically defended as being an autograph work by Hals, in opposition to my recent assessment that it is a workshop copy.16 My judgement is not based on vague differences in taste, but on undeniable visual evidence. Firstly, when comparing the two artworks, the engraving cannot possibly have been based on the painting. Secondly, Hals’s style is palpable still in the engraving, within the limits of the different medium, while the two painted portraits of Scriverius and his wife Anna van der Aar (1576/1577-1656) (A4.1.5) differ in style.17

On closer examination, there are several elements in the engraving that cannot have been copied from the present painting. The hand and cuff are more consistently modelled in the engraving and are closer to Hals’s style of painting than the flat hand in the painting, which is executed in hesitant short dashes [11][12]. To the left of the hand, the engraving shows a section of white cuff, which is covered in turn by a piece of black cloth, suggesting shimmering silk. The latter corresponds to the dark cloth below the ruff, which equally stands out against the matte black-grey fabric of the cloak. In the painting, these fabrics are not differentiated at all. Instead, the copyist simply depicted the two grey folds as belonging to the cloak.[13][14] There are several such misunderstandings in the details. Any practician of the graphic arts and connoisseur of textile representation will confirm that it is practically impossible to develop a comprehensible structure of soft collar folds as in Jan van de Velde’s engraving while working from such a misinterpreted modello as the flat area around the collar in the painting. Note, for instance, the naive outer contour of the collar with its white dashes! Additionally, the ear in the engraving is three-dimensional and plausibly depicted and cannot be based on the poorly done equivalent in the painting. The facial features in the engraving are clearly modelled, whereas the painting has timid dashes in the hair, beard and creases of the face, and repetitive lines around the area of the eye [15][16]. Hals’s painterly approach of sculpturally modelling a likeness is plainly absent. Neither the present painting, nor its pendant displays the calligraphic brushstrokes and rhythmically angular colored edges that are, from the outset, a central element of the richness of Hals’s painting.

I already demonstrated the differences in execution in two illustrations in my monograph of 1989.18 Today’s easily accessible high-resolution digital images allow an even more accurate comparison of individual areas, as does the fact that the engraving is not reversed vis-a-vis the painting. Based on a high-resolution image and a very good impression of the engraving, the fine nuances and differences in modelling can be assessed, which would be lacking in impressions from a worn plate. An internet search may not immediately produce the desired result, as was the case for the present case, but the Royal Collection Trust provided a marvelous impression in suitable resolution. Today, the superior craftsmanship of the Haarlem engravings and their documentary value can only be grasped by looking at the various versions and their technical processing. In this case, the engraver appears to be a more reliable observer and imitator than the painter of the New York painting. The generally very well-preserved paint layer excludes an interpretation of the shortcomings as a result of retouching and flattening of the impasto. It follows that the painted likenesses of the Scriverius couple were created in the workshop after Hals’s lost modelli, which were most likely done on paper.

It seems plausible that the portraits were commissioned for both the sitters’ 50th birthdays. It is worth mentioning that the prosperous man of letters, Scriverius, had already had himself painted in 1609/1610, probably by Willem van Swanenburg (1580-1612).19 He would have himself painted again in 1649 by Pieter Soutman (c. 1593/1601-1657), a copy of which is in the Frans Hals Museum.20 For his 75th birthday he would commission another portrait, in a large format, from the then much more famous painter Bartholomeus van der Helst (c. 1613-1670), who had become successful in Amsterdam.21 Engravings were made after the first three portraits, with an especially extensive panegyric by Hugo de Groot (1583-1645) under the engraving by Cornelis Visscher (c. 1628/1629-1658) after Soutman’s painting.22 Scriverius’s personal motto ‘LEGENDO ET SCRIBENDO’ – ‘reading and writing’ – appears on all prints. It aptly resonates with the sitter’s last name and with his profession. Within the context of this concern with self-representation through paintings and prints, the instructional intention of Scriverius’s portrait commissions should be considered. For the purpose of self-representation, the work of the engraver is at least as important as that of the painter. Thus, the latter’s work is measured against its skill of representation, and not its virtuoso brushwork.23

10

Jan van de Velde (II)

Portrait of Petrus Scriverius (1576-1660), after 1626

Great Britain, private collection The Royal Collection, inv./cat.nr. 670167

© His Majesty King Charles III 2023

cat.no. C9

11

Detail of cat.no. C9

Jan van de Velde (II)

Portrait of Petrus Scriverius

Great Britain, The Royal Collection Trust

© His Majesty King Charles III 2023

12

Detail of cat.no. A4.1.4

13

Detail of cat.no. C9

Jan van de Velde (II)

Portrait of Petrus Scriverius

Great Britain, The Royal Collection Trust

© His Majesty King Charles III 2023

14

Detail of cat.no. A4.1.4

15

Detail of cat.no. C9

Jan van de Velde (II)

Portrait of Petrus Scriverius

Great Britain, The Royal Collection Trust

© His Majesty King Charles III 2023

16

Detail of cat.no. A4.1.4

A4.1.5 Workshop of Frans Hals, Portrait of Anna van der Aar, 1626

Oil on panel, 22.2 x 16.5 cm, monogrammed and dated lower center: FHF 1626

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv.no. 29.100.9

Pendant to A4.1.4

This painting was created as a pendant to the portrait of Petrus Scriverius (1576-1660) (A4.1.4). Both works display the same technique, using small, thin dashes of paint. This diverges from Hals’s supple, soft brushwork and his sparse, yet precise characterization of facial features and hands, which can even be found in small formats. Nevertheless, there is an echo of Hals’s observation of moving facial features in the present portrait. The design and detailed modelling of the features suggest a drawn or painted preparatory study that was created by Hals. This could have been made as a first stage in the artistic process, directly onto the support of the present painting. However, the un-painterly, stripy modelling of the edges, as can be found in the lips and around the eyes, nose, and forehead of the woman [17], differ from Hals’s other achievements and exclude his involvement in the execution.

The type of stripy detailing visible in the New York painting can also be observed in several other works in this section, such as the portraits of Johannes Acronius (1565-1627) (A4.1.7), Samuel Ampzing (1590-1632) (A4.1.9), Caspar Sibelius (1590-1658) (A4.1.12), Hendrik Swalmius (1577-1649) (A4.1.13), Adrianus Tegularius (c. 1605-1654) (A4.1.16) and Judith van Breda (1582-1640) (A4.1.14) [18]. In comparison with the equally small-sized Portrait of Jean de la Chambre (A1.87), the difference in brushwork becomes apparent. The monogram FHF, placed on the feigned oval frame, must not be understood as authorship initials of Hals himself. Instead, it should be seen as a sort of ‘brand’, applied in the context of a master responsible for his workshop production.

17

Detail of cat.no. A4.1.5

18

Detail of cat.no. A4.1.14

Workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Judith van Breda, 1639

Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen

Notes

1 Van Hall 1936, no. 680-1.

3 ‘Rector Screvelius monstrabat et suam effigiem ab Halsio, pictore Harlemensi, in tabella pictam admodum vivide […]’. Aantekeningen betreffende meest Nederlandse schilders en kunstwerken, Utrecht University Library, Hs. 1781 (Hs 5 J 21), fol.17v.

4 Bijl 2005, p. 54.

5 Valentiner 1923, p. 306.

6 Pieter de Grebber, Portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius and his family, 1625, oil on canvas, 130 x 171.6 cm, Amsterdam, Amsterdam Museum, inv.no. 131 (on loan from Stedelijk Museum Alkmaar).

8 Bijl 2005, p. 47-58.

9 ‘[…] deur een onghemeyne manier van schilderen/ die hem eyghen is/ by nae alle over-treft/ want daer is in sijn schildery sulcke forse ende leven/ dat hy te met de natuyr selfs schijn te braveren met sijn Penceel/ dat spreecken alle sijne Conterfeytsels/ die hy gemaeckt heeft/ onghelooflijcke veel/ die soo ghecolereert zijn/ dat se schijnen asem van haer te gheven.’ Schrevelius 1648, p. 383. See also Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 142.

10 ‘Cum tot dura vagae fernaverit ora iuventae,/ Viribus eloquy, Palladijsque minis;/ Dignus erat Mathame tuo Schrevelius aere, […]’. See also Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 141.

11 Today, only a copy after the original companion piece survives (B1). It depicts Maria van Teylingen, her features identical to those in the 1625 family portrait by Pieter de Grebber. Having a portrait painted of one’s wife was usually a private concern, contrary to commissioning an engraved portrait that would circulate widely.

12 Grimm 1989, no. K6.

13 Grimm 1989, p. 55, fig. 48.

14 Neumeister 2005, p. 166.

15 See Langereis 2001, p. 110,128.

16 Liedtke 2007, vol. 1, p. 274-283; New York 2011, p. 37-39.

18 Grimm 1989, p. 248-249.

19 See the print featuring this early likeness: Willem van Swanenburg, Portrait of Petrus Scriverius, 161 x 105 mm, The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History.

20 After Pieter Soutman, Portrait of Petrus Scriverius, oil on canvas, 82.8 x 69 cm, Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. OS I-666.

21 Bartholomeus van der Helst, Portrait of Petrus Scriverius, 1651, oil on canvas, 114.5 x 98.5 cm, Leiden, Museum de Lakenhal, inv.no. 1445.

22 Cornelis Visscher II after Pieter Soutman, Portrait of Petrus Scriverius (1576-1660), 1649, 405 x 293 mm, The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History.

23 See also A4.1.1A for a similar case.