A1.45 - A1.58

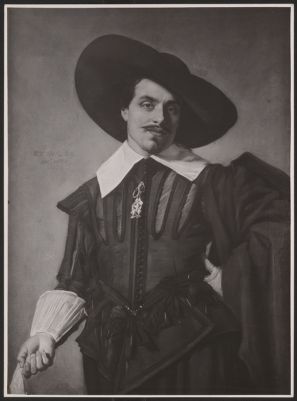

A1.45 Frans Hals, Portrait of a man, c. 1629-1630

Oil on panel, 68 x 58 cm

Mexico City, Museo Nacional de San Carlos, inv.no. 10425

On the basis of the style of the collar and doublet, as well as the smooth modelling and emphasis on three-dimensional volume, this portrait is typical for the period around 1630. The sitter is placed rather tightly within the composition and it remains to be examined whether the panel was cut down in size. A faithful copy – probably from the 19th century – in the Alte Pinakothek shows an identically narrow composition.1

A1.45

© Museo Nacional de San Carlos-INBAL-Secretaría de Cultura

Photo: Eduardo Galindo Vargas

A1.46 see: A3.15

A1.47 see: A3.16

A1.48 Frans Hals, Portrait of a man with a black hat and gloves in hand, 1630

Oil on canvas, 115 x 89.5 cm, inscribed and dated upper right: AETAT SVAE 52 / AN° 1630

New York, art dealer Otto Naumann, by 2011

Together with the Laughing cavalier (A1.16), this painting was described in The Times of 7 January 1888 as follows: ‘the solemn gentleman in black [...] of the dignified type which Hals painted with so much mastery and style (which) many will prefer [...] to the more showy effect presented by the Cavalier’.2

After the cleaning that took place after the 1988 auction, the date could be identified as 1630, instead of 1639, thus placing the portrait close to Portrait of a man from the same year [1], in terms of composition and tonality.3 If we look at the detailed execution of the three portraits of standing gentlemen from 1630 – the present painting, the just mentioned Portrait of a man and the Portrait of Cornelis Coning [2] – different perceptions of light effects and surface qualities become apparent. These can be understood as separate styles of execution. In this comparison, the stupendous quality of the facial section of the present painting becomes particularly clear, serving as a point of reference for the style that is entirely the master’s own. Also the merely fluidly sketched hand corresponds to this assessment.4

Valentiner's suggestion of a possible pendant in the Portrait of Cunera van Baersdorp (A1.23) cannot be upheld.5 Body posture and proportions do not match, and the female portrait is definitely earlier in style. The matching canvas sizes can often be attributed rather to a similarity in loom width and the utilization of available materials rather than to a matching of pendants. The high loss ratio of surviving pictures makes a discovery of a matching pendant a rare occasion

A1.48

1

Frans Hals (I) and workshop, possibly Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck

Portrait of a man, possibly Godfried van den Heuvel, 1630

canvas, oil paint, 116.7 x 90.2 cm

upper right: AETAT SVAE 36/AN. 1630

Great Britain, The Royal Collection, inv.no. RCIN 405349

© His Majesty King Charles III 2023

cat.no. A3.16

2

Frans Hals (I) and workshop

Portrait of Cornelis Hendricksz. Coning, 1630

canvas, oil paint, 108 x 81.3 cm

left: AET SVAE 29/AN⁰ 1630

Allentown Art Museum, inv.no. 1981.030.000

© Foto A. Frequin

cat.no. A3.15

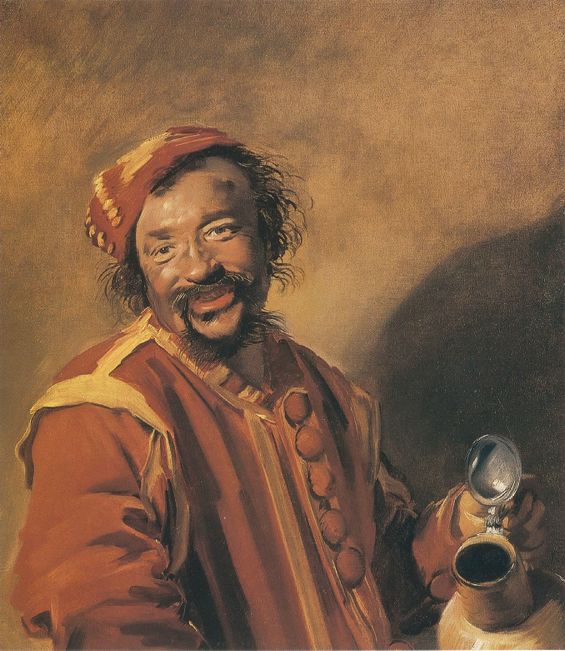

A1.49 Frans Hals, The merry drinker, c. 1630

Oil on canvas, 81 x 66.5 cm, monogrammed lower right: FH

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.no. SK-A 135

The sitter is presented as emerging frontally towards the viewer, with a demonstrative gesture of his proper right hand with the fingers spread and holding a goblet filled with white wine in the other. His mouth is open as if speaking, the eyebrows raised as if he were about to make a spirited pronouncement. The light reflections in the glass appeal to the sense of Sight and offer something for Taste as well, as both these senses constituted the sensual and transient nature of man in contemporary understanding.6 These connotations were an indispensable complement to a particular type of person or a conspicuous form of action; they added deeper meaning to the vibrancy of a captured moment in life and turned the painting into an object of learning and knowledge. Nature's elements could be experienced in the distinctive liquid of wine as well as in the blaze of light that temporarily illuminates the vital impulses on the sitter's facial features for the viewer. With this picture, Hals ultimately transformed the subject matter of the Utrecht Caravaggists into an original, innovative approach. Snapshots of body movements now became moments of facial expression that set the tone for everything else.

Slive raised the question of whether the present sitter could be the innkeeper Hendrick den Abt, who wanted to consign the painting Peeckelhaering (possibly A1.50 or A1.51) and three other works by Hals to an auction in 1631.7 This is conceivable, while the picture is a depiction of action or in fact a genre painting that instrumentalizes the sitter to illustrate a universal meaning. With his didactic gesture and tousled hair and beard, the present sitter is close to the two Peeckelhaering paintings. The medal on the man's chest shows a portrait which was identified as that of Prince Maurice of Orange (1567-1625) by Hofstede de Groot.8 The meaning of this, however, remains to be interpreted. Even though Hals's genre scenes were clearly based on the appearance of their sitters, they are above all a mirror of human emotions and conditions. Therefore, The merry drinker is not a portrait commemorating a civic guard member for posterity, as suggested by the title of the picture in the most recent catalogue of the Rijksmuseum.9

The painting had been bought for the newly founded Rijksmuseum as early as 1816 and was thus one of the earliest acquisitions of a work by Hals for a Netherlandish museum. Its comparatively high price at the time was 325 guilders, yet a painting by Jan Both (c.1615/1622-1652) achieved 5.610 guilders at the same auction in Warmond, near Leiden.10

A1.49

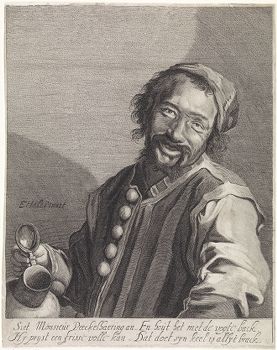

A1.50 Frans Hals, Peeckelhaering, c. 1630-1631

Oil on canvas, 75 x 61.5 cm, signed lower right: f.hals.f.

Kassel, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, inv.no. GK 216

The depicted person in this painting is identifiable through an engraving by Jonas Suyderhoef (1614-1686), which is inscribed ‘Look at Monsieur Peeckelhaering / he praises a cooling, brimful mug / And is constantly occupied with the wet vessel / For his throat is always dry.’[3].11 Peeckelhaering was a standard figure in the popular stage plays of the time. The colorful clothing with the large buttons was the signature outfit for a fool. The name Peeckelhaering refers to a greedy gobbling up of pickled herring, followed by a commensurate thirst.

Hals's invention of depicting a man's drunken laughter with shaggy hair must have soon become popular, since it was one of the few genre paintings by him to be published as an engraving during his lifetime. In a reduced size and entitled Nugae venales (jokes for sale), the motif was also used as the title page of an anthology of jokes printed in 1648 (C19), but without crediting Hals. Furthermore, the picture appears in the background of two paintings by Jan Steen (1626-1679), one of them being So de Oude songen, so pypen de Jongen in Berlin (B7), where it is shown as a pendant to a lost version of Malle Babbe (A1.103, A4.2.32, A4.2.34).12

A reference for dating the present painting may be a list of paintings owned by Haarlem inn-keeper Henrick Willemsz. den Abt, which he intended to put up for auction, dated 17 November 1631. The list includes a ‘peekelharing van Frans Hals’.13 Based on this documentary evidence, Jasper Hillegers developed an inspiring hypothesis. He pointed to the tavern-like background of So de Oude songen, so pypen de Jongen that Steen probably painted during his time in Haarlem between 1660 and 1670. We can imagine a similar room as the setting for a meeting between the painters Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641) and Frans Hals, probably in 1631 or 1632 when Van Dyck visited The Hague. According to Houbraken's report of 1718, Hals was in a tavern when the other painter arrived.14 There, Van Dyck could have seen the Peeckelhaering painting, which inspired him to create his portrait of the art dealer François Langlois (1588-1647), painted during the same period [4].15 Karolien de Clippel was the first to notice the fascinating dependence of Van Dyck's unusual portrait on Hals's Peeckelhaering.16 Even the unusual spelled-out signature on Hals’ painting could find an explanation in the public exhibition: ‘then every literate person who came into the inn would know who had painted the picture’.17 Whether Peeckelhaering actually hung in the tavern and remained there for thirty years and more, cannot be verified. It reappeared first as no. 363 in the 1749 inventory of the Kurhessische Gemäldegalerie in Kassel.18

A1.50

© Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister

3

Jonas Suyderhoef

Peeckelhaering, after 1630-1631

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-60.667

cat.no. C18

4

Anthony van Dyck

Portrait of François Langlois dit Chartres (1589-1647) as 'savoyard'

Birmingham (Great Britain), The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, inv./cat.nr. 97.4/6567

A1.50a Anonymous, Peeckelhaering

Oil on canvas, 78 x 68 cm, monogrammed lower right: FH

Sale New York (Sotheby’s), 21 May 1998, lot 197

Copy after the Kassel Peeckhelhaering, probably 17th-century.

A1.50a

A1.51 Frans Hals, Peeckelhaering, c. 1630-1631

Oil on canvas, 72 x 57.5 cm, monogrammed lower right: FH

Leipzig, Museum der Bildenden Künste, inv.no. G 1017

The traditional title of this painting, Mulatto, is misleading and offensive. Heiland explored the history of its reception with changing titles since 1887, and according to her research, the portrait-like title Joyeux Mulâtre was first used in 1889 at an auction in Paris.19 Slive therefore emphasized the sole historically correct title as Peeckelhaering, as the theatrical character in the painting is based on the same sitter, wearing the same outfit as in the painting in Kassel (A1.50).20

The paint layers of the present picture have suffered from cleaning and an earlier relining. Unfortunately the edges were trimmed, especially along the lower edge, but also on the left, where the fingertip and hand contour are now cut off by the frame. It is not clear how the painting looked originally along the lower edge and in the head and hair. Based on the engraving of c. 1670, the hair was wider and wilder, and a tuft of hair or feathers was lifted by the breeze on the right shoulder [5].

While older Leipzig museum catalogues refer to traces of a date next to the monogram, these are sadly no longer visible today. There are no other documents that provide indications for dating the painting. Especially the loose brushwork, with opaque shades of grey and black in the depiction of the dark-skinned figure, exceeds anything painted by Hals in the 1620s. A date can only be based on the general approach to shape and tonality, which is certainly further developed in this case than in Verdonck of 1627 (A1.34) or in the two roundels in Schwerin (A1.35, A1.36). In comparison, the disintegration of facial modelling into fluid transitions between light and shadows in the Leipzig picture by far surpasses that in The Merry Drinker (A1.49) and the Kassel Peeckelhaering (A1.50). Nevertheless, the approach to the costume is almost identical in both depictions of Peeckelhaering. Even though the sitter's beard is slightly different, not much time appears to have passed between the two variants.

The use of the present motif, together with the Portrait of a man (A3.34) in the engraving The Mountebanck Doctor and his Merry Andrew by Edward Davis (c. 1640-c. 1684) is of particular interest [5]. It confirms the early presence of paintings by Frans Hals in England. While the artist's name was spelled in various ways, from ‘Franc Hault’ to ‘Haultz’ or even ‘France Hals’, his works as such were appreciated, as several copies demonstrate. Slive mentions a Merry Andrew, possibly the present picture, in a London sale in 1765. The price of 10 shillings, 10 pence would present a negative record.21

The composition of the present painting is related to that of a workshop painting, where the figure in the foreground appears to be a reversed variant of Peeckelhaering’s posture [6]. This painting depicts two laughing boys, the one in front holding a coin. In my monograph of 1972 I had therefore assumed that the indistinct hand of Peeckelhaering was caused by overpainting a corresponding representation.22 In the meantime, restoration has revealed the original finger movement: the hand gesture is disparaging, with an outstretched finger – ‘not worth sticking your finger out’. Blankert pointed to the adoption of this gesture in representations of the laughing philosopher Democritus.23 The stylistic features of the workshop painting also match the supposed date of the Leipzig painting date of c. 1630-1631. The former is reproduced in reverse in a mezzotint by Wallerant Vaillant (1623-1677) (C21).

A1.51

Photo: Museum der bildenden Künste Leipzig | Punctum B. Kober

5

Edward Davis

Portrait of Two Men, c. 1670

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1850,1109.18

© The Trustees of the British Museum

cat.no. C20

6

Workshop of Frans Hals (I)

Two laughing boys, one holding a coin, c. 1630-1632

oil paint, panel, 62 x 51 cm

formerly Washington, private collection

cat.no. A4.2.14

A1.52 see: A3.18

A1.53 see: A3.19

A1.54 see: A3.20

A1.55 Frans Hals, Portrait of an old woman, c. 1633

Oil on canvas, 40 x 37.5 cm

Sale New York (Christie’s), 30 January 2013, lot 29

The portrait, which sadly survives only as a fragment, demonstrates the same angular modelling of the central facial features as the 1633 Portrait of a woman in Washington (A1.57). A wan smile and a mischievous expression in the tired eyes indicate a friendly but acerbic character. The clarity of the accents of expression around the eyes, nose and mouth are typical for this phase in the development of Hals's style and are drawn with very few brushstrokes. In parts, the paint layers are thin, probably due to rubbing, leaving the hairline and the transition between the forehead and the white cap indistinct. In the same way, the pattern of the dark dress has become faint. The surface structure of the millstone collar has also become flattened through abrasion. Yet, all areas that are visible today can be attributed to Hals's confident capture of nuances.

A1.55

© 2013 Christie's Images Limited

A1.56 Frans Hals, Portrait of a man, 1633

Oil on canvas, 64.8 x 50.2 cm, monogrammed, inscribed and dated center right: FH / AETAT SVAE 3… / AN° 1633

London, National Gallery, inv.no. NG1251

The canvas was slightly trimmed picture along the right hand edge, cutting off the last digit of the sitter's age. The paint layers in the shaded areas on the right of the face have become transparent. Overall, this loosely painted portrait demonstrates a significant new manner of accentuating in Hals's faces, which specifically creates more angular shadows, especially around the nose and mouth. The master’s brushwork has thus reached another level of independence, even in commissioned portraits.

A1.56

A1.57 Frans Hals, Portrait of a woman, 1633

Oil on canvas, 102.5 x 86.9 cm., inscribed and dated upper left: AETAT SVAE/ AN° 1633

Washington, National Gallery of Art, inv.no. 1937.1.67

After the museum's examination in 1985, it was revealed that the paint layer of this painting reaches as far as the edges of the folded canvas today, measuring 105.6 x 89.4 cm overall. Since the folded edges also lack the marks of the original stretcher, the original size must have been even bigger. And indeed, in the 1817 sale catalogue it is listed as measuring approximately 125 x 92 cm.24 In this context, Wheelock again brought up Valentiner's and Trivas's suggestion of a pendant relationship with the Frick Collection’s Portrait of a man (A1.41).25 This is conceivable, when considering the reconstructed size of both pictures and the posture and turn of the two sitters. Yet, Wheelock’s comparison with the Van der Meer portrait pendants (A3.19, A3.20) demonstrates that the woman in the present portrait would be too large and heavy in relation to her supposed counterpart in New York. Also, she would be placed a little too high, and not at the same eye level. Additionally, based on today's opportunities for comparison and the present stylistic criteria, the picture in the Frick Collection can be dated to around 1627-1628 and would thus not be eligible as a candidate for the companion piece. One exception from the usual simultaneous creation of pendants would only be the De Clercq and Van Steenkiste pair (A1.42, A1.72A). Only the examination of the canvases in Washington and New York, and analysis of the pigments used in the backgrounds – which should be similar in both instance – can confirm or reject the hypothesis more definitely.

The Portrait of a woman, whose posture is similar to that of Cornelia Claesdr. Vooght of 1631 (A3.20), does suggest a matching male counterpart was created as a companion piece. However, is is highly unlikely that the missing pendant can be found among the surviving works known today, which only represent a small part of Hals’s original production.

A1.57

Photo courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

A1.58 Frans Hals, Portrait of Pieter van den Broecke, 1633

Oil on canvas, 71.2 x 61 cm

Hampstead (London), Kenwood House (The Iveagh Bequest), inv.no. 51

The Haarlem engraver Adriaen Matham (1599-1660) copied the present portrait, not reversed, and included an inscription that mentions the sitter being 48 years old in 1633 – providing a probable date for the painting [7] (C24). A smaller version of this engraving was used in Pieter van den Broecke's (1585-1640) publication about his adventures as a traveler to East India and West Africa.26 Van den Broecke was a successful merchant and commercial fleet commander, who was highly honored for his 17 years of service at the East India company in Persia, Arabia, India and Batavia (today's Jakarta). As a gift of appreciation, he had received a gold chain worth 1200 guilders, equivalent to the value of a house at the time. In the portrait, he is depicted wearing the chain over his shoulder, positioned as an officer at sea with his right arm resting on a commanding staff. His hair is somewhat untidy, making him appear weather-beaten. It is interesting that this man upheld a personal connection with Hals: together with the engraver Matham, he became the godfather of Hals's daughter Susanna in 1634.27

Sadly, the painting’s paint layer is abraded and flattened throughout by lining of the canvas. Hals’s free brushstrokes are unfortunately only partly preserved in the sitter’s facial features, which are characterized by a lifetime of adventure. The comparison between Matham’s engraving and the painting in its present condition clearly demonstrates the loss in clear modelling along the folds of the dark clothing, in particular in the sleeves. The small amounts of lead white added to the different shades of grey have lost most of their opacity.

A1.58

© Historic England Archive. Reuse not permitted

7

Adriaen Matham

Portrait of Pieter van den Broecke (1585-1640), dated 1633

Philadelphia (Pennsylvania), Philadelphia Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 1985-52-34432

cat.no. C24

Notes

1 Oil on panel, 69 x 57.8 cm, Munich, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen - Alte Pinakothek München, inv.no. 14127. Interestingly, the copy was donated by artdealership Julius Böhler to the collection of forgeries at the Doerner Institut, in 1970. With thanks to Bernd Ebert for his assistance in locating the copy.

2 See Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 80, note 42.

3 Sale London (Sotheby’s), 7 December 1988, lot 96.

5 Valentiner 1921, p. 168.

6 See: Kauffmann 1943, p. 141 for a connection of this painting to the tradition of depicting the Five Senses.

7 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 1 (1970), p. 111.

8 Hofstede de Groot 1970-1928, vol. 3 (1910), p. 17.

9 Bikker et al. 2007, vol. p. 171: A civic guardsman holding a berkemeijer.

10 Sale Warmond, 31 July 1816, lot 5 – Both, and lot 13 – Hals (Lugt 8948).

11 ‘Siet Monsieur Peeckelhaering an ../ Hy pryst een frisse volle kan ../ En hout het met de vogte back./ Dat doet syn keel is altyt brack’.

12 The other painting by Steen featuring Peeckelhaering as a painting on the wall, is The doctor’s visit, oil on panel, 49 x 42 cm, London, Wellington Museum (Apsley House).

13 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 385-386, doc. 58, with reference to previous literature.

14 Houbraken 1718-1721, vol. 1, p. 90-91.

15 J. Hillegers in Haarlem 2013, p. 115.

16 K. de Clippel in Haarlem 2013, p. 50.

17 A. Tummers in Haarlem 2013, p. 88.

18 Haupt-Catalogus von Sr Hochfürstl. Durchlt Herren Land Grafens Wilhelm zu Heβen, sämtlichen Schilderyen und Portraits. Mit ihren besonderen Registern. Verfertiget in Anno 1749, no. 363. Manuscript kept at the Staatliche Museen Kassel.

19 Heiland 1985, p. 6.

20 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 220. In September 2021, the Museum der Bildenden Künste Leipzig finally officially changed the painting’s title to Peeckelhaering.

21 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 1 (1970), p. 97.

22 Grimm 1972, p. 75-76.

23 Blankert 1967, p. 57, note 57.

24 Sale Amsterdam (Schley), 28 August 1817, lot 20 (Lugt 9211): ‘hoog 48, breed 36 duimen’.

25 Wheelock 1995, p. 69-72; Valentiner 1923, p. 109; Trivas 1941, p. 39, no. 41.

26 P. van den Broecke, Korte historiael ende journaelsche aenteyckeninghe (…), Haarlem 1634.

27 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, doc. 62.