A4.1.10 - A4.1.14

A4.1.10 Possibly Frans Hals, or his workshop, Portrait of Pieter Christiaansz. Bor, 1634

Oil on panel, 24 x 20.5 cm, monogrammed upper right: FH; dated upper right: An⁰ 1634; inscribed upper left: AEta 75

Formerly Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen

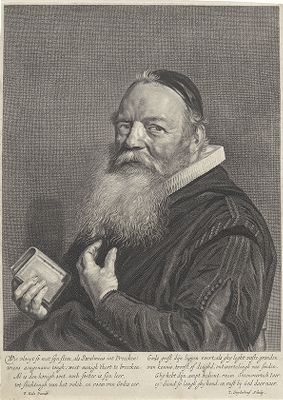

This portrait of Pieter Christiaansz. Bor (1559-1635) was lost in the fire at the Boijmans Museum in 1864. Adriaen Matham's (c. 1599-1660) engraving of 1634 [1] gives a precise and convincing rendering of the sitter's facial features and is stylistically plausible to have been based on a modello by Hals. Whether the former model was identical with the painting from Boijmans, or whether it was delivered to the engraver in a different form – on paper perhaps – cannot be determined without any illustration of the Rotterdam panel.

Several old copies of Bor's portrait are known, which are listed by Slive and in the documentation files of the RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History in The Hague.1 The coloring and style of these copies are mostly consistent, and the present painting’s size and inscription seem to fit into this group as well. Based on an assessment of the quality of the surviving copies, the authorship of the lost picture remains unclear. Had it been largely of the same quality as the others, I would not consider it an autograph work by Frans Hals himself.

1

Adriaen Matham

Portrait of Pieter Christiaansz. Bor (1559-1635), after 1637

The Hague, RKD – Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis (Collectie Iconografisch Bureau)

cat.no. C26

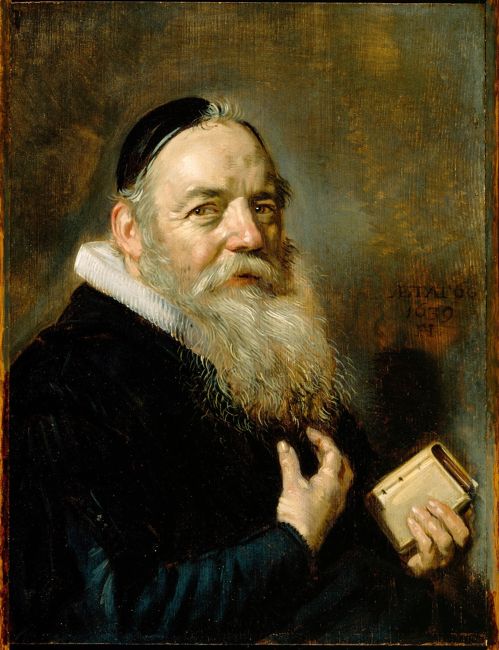

A4.1.10a After Frans Hals, Portrait of Pieter Christiaansz. Bor

Oil on copper, 29 x 24 cm, monogrammed lower right: FH; dated upper right: An° 1633; inscribed upper left: ÆTA 75

Aachen, Suermondt-Ludwig-Museum, inv. no. GK 181

The sitter in this portrait is the Haarlem notary Pieter Christiaansz. Bor (1559-1635), who was held in high regard in the 17th century.2 Later, he became councilor and rentmeester-generaal for the province of North Holland, and subsequently was active as a poet and historian. His extensive publication on the Netherlandish wars guaranteed him sustained fame.3 This also explains the posthumous demand for portrait-paintings and -engravings of the author.

This present copy conveys an impression of the original painting’s coloring. It takes precedence among the present list of copies of the portrait of Bor, because until quite recently, the museum considered it to be a work by Frans Hals himself.4 Nevertheless, there is no reason to consider it a work by the Hals workshop, as suggested by Atkins.5 The fact that the coloring adheres to Hals's original painting is self-explanatory and is no more an adequate basis for an attribution, than the presence of the FH monogram. These capital letters are the most easily imitated element in the picture and can equally be found in the other copies of the Bor portrait, as well as in many other paintings. It would be impossible to distinguish a ‘seemingly genuine signature’ in a copy, when even the original works do not give a clear indication which of the signatures may be autograph. A longer hand-written signature on a document would offer more clues. In the present case, the copy is further discredited by its date of 1633. By comparison to the engraving [1], this copy diverges from the original composition in depicting a book on the edge of the feigned oval, which constitutes a reference to the learned historian and author's occupation.

A4.1.10a

A4.1.10b After Frans Hals, Portrait of Pieter Christiaansz. Bor

Oil on panel, 24.9 x 21.5 cm, monogrammed lower right: FH; inscribed upper left: Aeta 75; dated upper right: An° 1634

Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, inv.no. 1277 (OK)

A4.1.10b

A4.1.10c After Frans Hals, Portrait of Pieter Christiaansz. Bor

Oil on canvas, 22.5 x 19.8 cm, monogrammed lower right: FH; inscribed upper left: Aeta 75; dated upper right: An° 1634

Sale Vienna (Dorotheum), 15 December 2023, lot 165

A4.1.10c

© Dorotheum, Vienna

A4.1.10d After Frans Hals, Portrait of Pieter Christiaansz. Bor

Oil on copper, 26 x 23.5 cm, monogrammed lower right: FH

Private collection Rosenthal

A4.1.10d

A4.1.10e After Frans Hals, Portrait of Pieter Christiaansz. Bor

Oil on copper, 17.9 x 14.5 cm, monogrammed lower right: FHF

Sale Amsterdam (Fr.Muller), 25 November 1924, lot 146

A4.1.10e

A4.1.10f After Frans Hals, Portrait of Pieter Christiaansz. Bor

Oil on copper, 25.5 x 24 cm, monogrammed lower right: FH; inscribed upper left: Aeta 75; dated upper right: An° 1634

Paris/New York, art dealer Franz Kleinberger

A4.1.10f

A4.1.10g After Frans Hals, Portrait of Pieter Christiaansz. Bor

Oil on canvas, 22 x 18.5 cm

Sale Nürnberg (Kunsthaus Klinger Auction), 13 November 1993, lot 59

The book does not appear in this version.

A4.1.11 Workshop of Frans Hals, Portrait of Isaac Abrahamsz. Massa, c. 1635

Oil on panel, 21.3 x 19.7 cm, monogrammed center right: FH

San Diego, San Diego Museum of Art, inv. no. 1946.74

The present painting is an especially instructive document on the production of modelli for engravings in Hals's workshop. Its special position is first marked by the sitter’s personal motto In Coelis Massa on the engraving by Adriaen Matham (c. 1599-1660) that features the same portrait [2]. The engraved representation, with verses below praising Massa and hinting at his expectation of eternal happiness, could possibly be understood as a premature means of commemoration. The author of these lines, whose initials C.M. may belong to Massa's brother Christiaan, may have also been the person who commissioned this portrait, prompted by the severe illness and the expected death of the sitter. Nevertheless, Massa did not die in 1635, but lived on until 1643.

While the present painting’s paint layers are much abraded, two distinct levels of quality are still recognizable. The modelling of the chest and arms, particularly in the sleeve on the left, must have been spatially clearer in the original execution. The clumsy foreshortening of the arms and the weak execution of hands and cuffs, as well as the uniform design of the collar, are carried out by a less practiced hand overall – as opposed to the finer details in the face. With its sensitively graduated lighting and coloring, this is the best part of the portrait. However, the slightly rubbed paint layers reveal that this area was traced, as it shows a recognizable line of dots on the edge of the lips, on the left side of the moustache, and on the eyelids and eyebrows. This suggests that there was a single design for the face, including all the details, which only appear to have been partly copied in this case. This design was probably painted by Hals on cheap material such as paper or parchment, which would have easily permitted tracing, be it onto a copper plate or on a panel of the same size. The confidently depicted foreshortened hand in the engraving would certainly have required a similarly exact modello as would the head area, which the somewhat weakly rendered hand in the painting could not provide. The representation of the slightly compressed upper body and the hesitant handling, especially in the arm akimbo in the engraving, can only be explained by the probability that the artist was working from a rough preparatory sketch, on the basis of which they worked out the further details themselves. Most likely, Hals had designed the entire composition for this portrait, or, minimally a sketch for the face that could be used as a traceable model. If the tracing dots that are visible here, consist of a carbonic pigment, further traces could be explored in this and other pictures by means of infrared-reflectography.

A4.1.11

© The San Diego Museum of Art: gift of Anne R. and Amy Putnam. www.SDMART.org

2

Adriaen Matham

Portrait of Isaac Abrahamsz. Massa (1586-1643), between 1635 and 1643

Haarlem, Noord-Hollands Archief, inv./cat.nr. NL-HlmNHA_53009764_M

cat.no. C27

A4.1.12 Workshop of Frans Hals, Portrait of Caspar Sibelius, 1637

Oil on panel, 26.5 x 22.5 cm, inscribed, dated, and monogrammed center right: ÆTAT SVÆ 47 / AN° 1637 / FH

Formerly USA, private collection Billy Rose; destroyed by fire in 1956

Caspar Sibelius (1590-1658) was a priest from Deventer, who worked there as a preacher for three decades. His own description of his life is preserved as a manuscript in the local library of the town. Hals probably painted his portrait in January 1637 during the time Sibelius came to Bloemendaal, near Haarlem, to attend his daughter’s wedding. On the basis of this portrait, two engravings were created by Jonas Suyderhoef (1614-1686), the first as early as 1637 [3] in composition and dimensions identical with the present picture, yet reversed. The second engraving (C30), dated 1642, renders the painted modello on a smaller scale and not reversed. As far as we can see from the photographs, the painting’s execution was hesitant and different from Frans Hals’s own brushwork. To quote Slive, the painting 'was either badly restored or was a copy by another hand after one of Suyderhoef’s prints’.6 In any case, the engravings show a confidently modelled body and facial features that are conveyed to the smallest detail of expression. Such characterics seem to not have an equally clear equivalent in the painting. Considering the findings in other combinations of engravings and paintings, it seems probable that this portrait was also painted after a lost model. However, had it actually been the damaged and disfigured original Slive spoke about, the subtle expression in the prints would be a singular achievement by the engraver. Furthermore, it is questionable to what extent Hals involved his assistants in the production of modelli for engravings, and from what time onwards. In my view, this seems only to become apparent in the portrait of Theodore Bleuet of 1640 (C36) and then in works from the 1650s onwards (A4.1.16, A4.1.17, A4.1.18).

A4.1.12

3

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of Caspar Sibelius (1590-1658), after 1637

The Hague, RKD – Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis (Collectie Iconografisch Bureau)

cat.no. C29

A4.1.13 Workshop of Frans Hals, Portrait of Hendrick Swalmius, 1639

Oil on panel, 27 x 20 cm, inscribed, dated, and monogrammed center right: AETAT 60/1639/FH

Detroit, Detroit Institute of Arts, inv.no. 49.347

Pendant to A4.1.14

A4.1.13

A4.1.14

This painting was rediscovered in 1934, having been known only through the engraving by Jonas Suyderhoef (1614-1686) [4]. The text on the print identifies the sitter as the reformed priest Hendrick Swalmius (1577-1649), who had been ordained in Haarlem in 1600, where he worked for over 46 years. The comparison with the engraving demonstrates that the painting was cut at the top and on both outer sides. This circumstance is additionally confirmed by the comparison with the pendant, a portrait of Swalmius’s wife Judith van Breda (A4.1.14), which corresponds in the sitter’s age and the picture’s proportions and which has retained its original size.7

Swalmius’s painted portrait and the engraving can be dated differently. The text under the engraving is a retrospective eulogy. It refers to Swalmius's 46 years of service and can therefore not have been published before 1646. The painting is dated 1639 and corresponds stylistically to the 1630s. Based on the assumption that portraits and engravings depicting priests were typically commissioned by their parishes, or by charitable foundations for whom they worked, the present portrait commission would have by far anticipated the commemorative purpose of the engraving. Was the portrait commission a preparatory measure, perhaps caused by an illness or should it be seen in view of Swalmius’s 40th work anniversary in 1640? Only a comparison between the painting and the engraving can answer this question. Was it possible for Suyderhoef to create his engraving on the basis of the 1639 painting – or would he have needed another modello that Hals would have created already in 1639? A comparison of enlarged reproductions of the engraving and the painting reveals a differentiated execution of both the facial features and the hands in the engraving, which is not based on the present painting. The innocently amiable face in the present picture, which is too large in proportion to the hands, falls far short of the kind gravity of the much more subtly modelled engraving [5][6].

With respect to the verses under the engraving, they state that Swalmius’s sermon in God’s honor was ‘sweet as honey’, that ‘the spirit of God’ moves his lips. Such expressions only match the serious demeanor in the engraving, which is at a similar level of expressiveness as Rembrandt’s (1606-1669) Portrait of a clergyman.8 In other words: Suyderhoef was a much more reliable copyist than Hals’s assistant who painted the portrait of Swalmius and his wife. Accordingly, Hals must have already created a modello for an engraving in 1639 for the devout commemoration by the parish, which had been copied for the purposes of the sitter and his family on a more durable panel support, complemented by a pendant featuring the sitter’s wife.

4

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of Hendrick Swalmius, after 1639

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-60.768

cat.no. C34

5

Detail of cat.no. A4.1.13

6

Detail of cat.no. C34, in reverse

A4.1.14 Workshop of Frans Hals, Portrait of a woman, possibly Judith van Breda, 1639

Oil on panel, 29.5 x 21 cm, inscribed and dated center left: ÆTAT 57 / 1639

Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, inv.no. 2498

Pendant to A4.1.13

As early as 1921, Valentiner identified this picture as the pendant to the Portrait of Hendrick Swalmius (A4.1.13), which was believed lost at the time.9 This identification was based on the female portrait’s composition and size, which correspond to the engraving of the Swalmius portrait.

The portrait renders a credible composition by Hals, in well-preserved colors. Nevertheless, the execution of the face is smooth and mechanical – see, for example, the repetitive parallel brushstrokes that render the hairline under the bonnet [7]. The handling of the collar and the clothing is also too even for Hals; this was carried out by another hand in fine dashes that differ from the master's brushwork. The modelling of the face and hands must be based on Hals's design, executed either in a separate preparatory sketch or as a first outline in the final panel. Hals clearly appears to have delegated the finishing of each individual button and collar fold to one of his assistants.

Valentiner presumed that the long inaccessible fragmentary Portrait of a woman from the Quincy Shaw collection in Boston (B15) was a copy after the present painting, or at least depicted the same sitter.10 Comparison with the more recent reproduction in the auction catalogue of Sotheby’s, where it was sold in 2008, has pointed out that the faces differ, especially in the area around the eyes.

7

Detail of cat.no. A4.1.14

A4.1.14a Anonymous, Portrait of a woman, possibly Judith van Breda

Oil on panel, 29 x 24.5 cm

Formerly Paris, private collection Adolphe Schloss

Copy after the abovementioned Portrait of a woman, possibly Judith van Breda (A4.1.14a).

A4.1.14a

Notes

1 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, no. L 11.

2 Not ‘Paulus’ Bor, as stated in Atkins 2012, p. 187.

3 First edition: P.C. Bor, Oorsprongh, begin en vervolgh der Nederlandsche oorlogen, 1621.

4 Fusenig/Vogt 2006, p. 136.

5 Atkins 2012, p. 187-188.

6 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 121.

8 Rembrandt or circle of Rembrandt, Portrait of a clergyman, 1637, oil on canvas, 132 x 109 cm, Antwerp, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, inv. no. 705.

9 Valentiner 1921, p. 218.

10 Valentiner 1921, p. 218.