A4.1.6 - A4.1.9

A4.1.6 Workshop of Frans Hals, Portrait of a man, 1627

Oil on copper, 20 x 14.2 cm, remains of date upper right: ..62..

Berlin, Gemäldegalerie der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, inv.no. 766

Today, the first and fourth digit of the date are no longer discernible, yet in 1883 Wilhelm von Bode read it as 1627.1 On the basis of the hand movement reaching out of the picture, the sitter was identified as Nicolaes le Febure (1589-1641), whose hand makes an identical movement in the lower right-hand corner of the Banquet of the Officers of the St George civic guard of 1626-1627 (A1.30).2 However, there is no resemblance between the faces of the men.

All the details appear to have been modelled in an insecure style that differs from that of Hals. Especially weak areas are the clumsily drawn ear, the left side of the collar with its incoherent stripes, and the dashes in the hand. This hand was probably copied after Le Febure’s hand in the above-mentioned civic guard portrait [1], and was unfortunately overpainted, respectively strengthened in a simplifying manner [2]. Today, the palm of the hand appears too long in relation to the foreshortened finger joints. The original design of the fingers, which was anatomically correct, is nevertheless still faintly visible underneath the upper paint layer. The present small-scale portrait may have been intended as part of a series of portraits. Probably Hals made a rough compositional sketch, as well as a design for the face.

A4.1.6

Photo: Christoph Schmidt; Public Domain Mark 1.0

1

Detail of cat.no. A1.30

Frans Hals (I)

Banquet of the Officers of the St George civic guard

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum

2

Detail of cat.no. A4.1.6

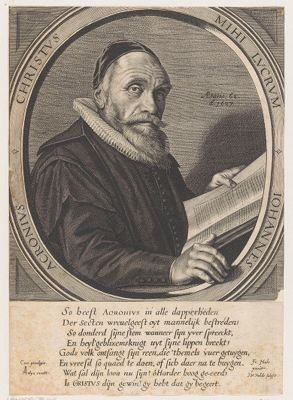

A4.1.7 Workshop of Frans Hals, Portrait of Johannes Acronius, 1627

Oil on panel, 19.3 x 17.1 cm, inscribed and dated upper right: AETAT SVAE 62 / A° 1627

Berlin, Gemäldegalerie der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, inv.no. 767

Johannes Acronius (1565-1627) was a priest who was first active in Eilsum, then in Groningen, in Wesel and in Deventer. In 1617 he became professor in Franeker, until 1619, when he was called to Haarlem to become pastor of the reformed parish of the principal church of St Bavo.3 Acronius was an influential preacher and became famous as a fighter against the Haarlem Mennonites.

The present portrait can be identified on the basis of the copper engraving by Jan van de Velde (1593-1641) [3]. A portrait was often created whenever an important personage left a specific place – for example René Descartes, who departed from Holland in 1649 – or when sickness or frailty gave rise to the apprehension of impending death; the same motivation can be assumed in this instance. The small-scale portraits of scholars and priests were then created in parallel to their engravings which were to be distributed to commemorate the deceased. Slive mentioned an extensive Dutch inscription on the back of the present picture, which lists the sitter’s achievements.4 Even though it was probably only added in the 18th century, it supports the interpretation of this portrait’s commemorative purpose.

The lively turn of the sitter’s gaze, with a slightly turned head, is an expressive movement that is in line with Hals’s manner of observation, which he may well have established in a preparatory portrait study. It is impossible to create such a characteristic and defined impression entirely from memory when the audience already has expectations of an individual likeness. For this reason, I would exclude a posthumous production of the present portrait, as was considered by Slive and Biesboer.5 Furthermore, the painterly execution of this Berlin picture with thin, short, lines drawn by the brush in the facial creases, the hair of the beard and on the ears, is certainly the work of an assistant; there is nothing that would indicate the master’s own brushwork. This also applies to the areas not necessarily based on immediate observation, such as the clothing and the hands. Therefore, the present portrait cannot be the modello, nor the main preparatory sketch for the much clearer representation in the engraving. With its size of 19.3 x 17.1 cm, the picture is of the exact same size as the engraving plus the text block. It follows that the painting was created on the basis of either the engraving, or on its lost original modello.

A4.1.7

Photo: Christoph Schmidt; Public Domain Mark 1.0

3

Jan van de Velde (II)

Portrait of Johannes Acronius (1565-1627), after 1627

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-76.146

cat.no. C11

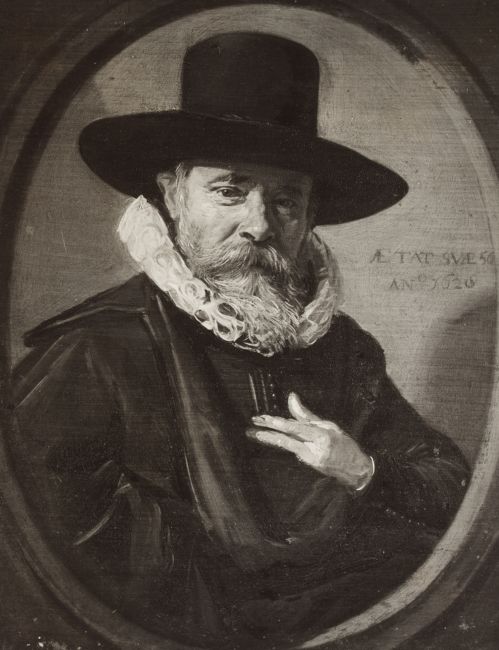

A4.1.8 Workshop of Frans Hals, Portrait of a man, 1628

Oil on panel, 22 x 17.5 cm, inscribed and dated center right: AETAT SVAE 56/ AN° 1628

Whereabouts unknown

This small picture is a variant of a portrait presenting the same features, namely the roundel in an English private collection, but reduced in size and showing slightly harder modelling [4]. In the present painting, the sitter’s upper body is turned more towards the viewer, which seems likely to have been based on direct observation of the sitter. Accordingly, the collar is turned differently, and the areas of the beard and ear diverge. These entirely plausible changes in the posture seem related to the nature of the commission and are an example for the multiple uses of model-studies in the Hals workshop. The hard reflections on the coat, and the equally rigid addition of the hand, suggest an execution by an assistant, who may not have been the same as the one who depicted the hands and clothing the above-mentioned variant (A3.11) and its companion piece (A3.12). The present painting’s inscription, declaring the sitter’s age to be 56, must be erroneous, especially as it is executed with an uneven distance between the letters and in two unparallel lines.

A4.1.8

4

Frans Hals (I) and workshop

Portrait of a man, 1628

panel, oil paint, 22.8 x 22.8 cm

England, private collection

cat.no. A3.11

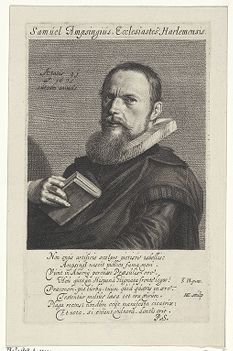

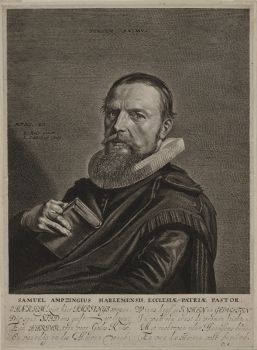

A4.1.9 Workshop of Frans Hals, Portrait of Samuel Ampzing, 1630-1631

Oil on copper, 16.4 x 12.4 cm, inscribed and dated center right: AETAT 40 / AV° 163...

New York, The Leiden Collection, inv.no. FH-100

The high-resolution images on the website of the Leiden Collection permit a much better assessment than all previously available illustrations.6 It becomes possible to compare all details precisely, setting new standards. Consequently, the relationship between the present painting and the two reversed engravings by Jan van de Velde (1593-1641) and Jonas Suyderhoef (1614-1686) becomes much clearer [5][6].7 At first glance, their representation is consistent with the painting. Both identify the sitter as ‘Samuel Ampzingius’, a man of the church from Haarlem. Both refer to their makers, the painter, as well as the engraver. The undated, large-scale engraving by Suyderhoef is more precisely detailed and executed in soft transitions. The smaller print by Van de Velde is inscribed AETATIS 41/ ao 1632. The additional text below the portrait indicates that it was probably created after Ampzing's death, that is, in the second half of 1632, whereas Suyderhoef’s engraving was most likely created around 1640.

As a priest, historian and poet, the sitter Samuel Ampzing (1590-1632) was an important personage in Haarlem, as well as in Dutch literature of the time. He was the first author to mention the brothers Frans and Dirck Hals (1591-1656), in his 1621 and 1628 verses praising the town of Haarlem.8 In 1621, their names are listed in a matter-of-fact overview of the more than fifteen artists working in Haarlem at the time. As Slive notes, Ampzing's praise in the 1628 version was slightly more emphatic:

‘Forth Halses, come forth,

Take here a seat, yours it is by right.

How dashingly Frans paints people from life!

How neat the little figures Dirck gives us!

Brothers in art, brothers in blood.

Nurtured by the same love of art, by the same mother’.9

However, these much-quoted words of praise pale in comparison with the similar, and sometimes more explicit words Ampzing used to refer to Hals’s colleagues. For instance, he wrote about the comparatively humble achievements of Hendrick Pot (1580-1657):

‘And Hendrick Pot must also justly bear his crown.

It is a miracle, what he achieves in these times

With his fine hand’.10

Above all, Ampzing was an active Calvinist preacher who wrote polemic pamphlets against the Catholic church in 1630 and 1632. He died on 29 July 1632. It is not known who commissioned the engravings with Ampzing’s portrait. The close connection between the date of the present picture and that of the 1632 engraving (C22) suggests public interest in an Ampzing-portrait, as does the fact that there was a subsequent engraving made depicting the same sitter. The eulogies that accompany the engravings, provided contemporaries with an interpretation of the portraits. According to the monogram P.S. below them, the author was Petrus Scriverius (1591-1660), who had worked with Ampzing on his book about Haarlem. It is worth noting that the first, smaller engraving was accompanied by a text in Latin. It contains the passage:

‘Ampzing’s fame, known to all, cannot die.

It lives on in the stricken face of the Ausonian bishop.

Ah! How many scars will you read on the Spaniard’s brow!

Why, devoted congregation, do you seek to have your Herald pictured on copper?

The wounded faces of so many men will bear witness to him’.11

The text refers to the theological polemics of the pugnacious Calvinist Ampzing, as expressed in his final pamphlets. At the same time, Ampzing’s version of the history of the siege and Spanish occupation of the valiant town of Haarlem is suggested as a heroic feat, as the sitter holds the book conspicuously in his hand – instead of a contemporary edition of the Bible, as Liedtke noted.12 Actually, Ampzing’s historical work in verse remained valid until the 18th century. The question directed at the ‘devoted congregation’, why it desires ‘to have its herald pictured on copper’ also answers the question as to whom commissioned the engraving. Ampzing was a preacher at the town’s principal church of St Bavo, whose parish councilors were responsible for the commission of the print, and probably also for that of the painted portrait.

Hals’s modello was used once more, almost a decade later, for the engraving created by Suyderhoef (C23). This time, the inscription is in Dutch and reads:

‘O Haerlem, look upon Ampzing’s appearance,

Which his city gives us that we may know him:

A shepherd true to the church of God,

And proficient in the Lord’s work,

Whose edifying verses and poetry uplift the pious with their deep gravity;

Rightly is he beloved of all Haarlem’s children and of the Lord’s people’.13

Van Thiel’s translation presented here, differs from Slive’s earlier version, which had said that Ampzing ‘gives us his city to read’, and instead says that the city has provided us with his likeness.14 This points to the source of Suyderhoef’s commission for another copper engraving: the town council of Haarlem, for which Liedtke presumes a date of c. 1640.15 Suyderhoef’s engraving matches the subject and composition of the present painting, but it is almost double the size, and displays a wider angle. Suyderhoef must have used a detailed modello with a similar expression, as also goes for the earlier engraving by Van de Velde.

Based on a detailed consideration of both prints, it must be concluded that this modello has not been preserved. The shape of the ear, the creases around the eyes and the design of the hand, as well as the folds of the coat seen in the engravings cannot be derived from their respective counterparts in the painting. While the painting shows a lively gaze with a neutral, even serene facial expression [7], Suyderhoef’s engraved portrait has a decidedly questioning gaze with two matching vertical creases in the forehead [8][9]. The painted version does not have the same psychological consistency. It would be impossible to create such a coherently expressive representation from the present, small-scale painting, and neither could it be derived from the enlargement of Van de Velde’s engraving. In addition, Suyderhoef could not have extracted the very ‘Halsian’ modelling of the fingers from Van de Velde or from the present painting, nor from a fictitious blending of both. Van de Velde and Suyderhoef were excellent engravers, but hardly the virtuoso masters of expression who might have single-handedly lifted the present painting into something more spiritual and coherent. Such a role reversal should be excluded.

Another comparison is even more striking here. Suyderhoef’s first engraving was made after the 1638 Portrait of Jean de la Chambre (A1.87). It is another small-scale print, which is identical in format to the painting. Both the print of De la Chambre and that of Ampzing date from the same period and depict a brightly-lit face and a bust and arm clothed in a black-grey doublet. When placed in direct juxtaposition the stylistic differences between the two pictures become clear. Ampzing’s portrait has no trace of the transformation of the clothing into an abstract pattern of diagonal stripe in shades of grey [10][11], and none of the verve in the brushstroke of the face and hair[12][13]. Anatomic details like the ear and hand are rendered awkwardly. Accordingly, the present picture should be considered to be the work of an assistant of Hals, based on a lost original.

A4.1.9

5

Jan van de Velde (II)

Portrait of Samuel Ampzing, dated 1632

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1898-A-20197

cat.no. C22

6

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of Samuel Ampzing (1590-1632)

The Hague, RKD – Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis (Collectie Iconografisch Bureau)

cat.no. C23

7

Detail of cat.no. A4.1.9

8

Detail of cat.no. C22, reversed

Jan van de Velde (II)

Portrait of Samuel Ampzing, 1632

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

9

Detail of cat.no. C23, reversed

Jonas Suyderhoef

Portrait of Samuel Ampzing

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History

10

Detail of cat.no. A4.1.9

11

Detail of cat.no. A1.87

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Jean de la Chambre, 1638

London, National Gallery

12

Detail of cat.no. A4.1.9

13

Detail of cat.no. A1.87

Frans Hals (I)

Portrait of Jean de la Chambre, 1638

London, National Gallery

Notes

1 Bode 1883, p. 86, no. 86.

2 Trivas 1941, no. 24.

3 See Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 31; Van der Aa 1852-1878, vol. 1, p. 43.

4 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 31.

5 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 31; Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 30.

6 https://www.theleidencollection.com/artwork/portrait-of-samuel-ampzing/

8 Ampzing 1621; Ampzing 1628.

9 ‘Komt Halsen, komt dan voord,/ Beslaet hier mee een plaetz, die u met recht behoord./ Hoe wacker schilderd Franz de luyden naer het leven!/ Wat suy’vre beeldekens weet Dirk ons niet te geven!/ Gebroeders in de konst, gebroeders in het bloed,/ Van eener konsten-min en moeder opgevoed’. Ampzing 1628, p. 371. See also: Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, doc. 41.

10 ‘En dan moet Heyndrick Pot sijn kroon ook billijk dragen./ ‘Tis wonder wat hy doet in dese onse dagen/ Met sijn suy’vre hand’. Ampzing 1628, p. 371.

11 ‘Non opus artificis scalpro pictisve tabellis;/ AmpsingI nescit publica fama mori./ Vivit in Ausonij percusso Praesulis oro./ Ho’u quot in Hispana stigmata fronte leges!/ Draconem. pia turba. tuum quid quaeris in aere.-/ Testentur melius laesa tot ora virum./ Plaga recons: non dum coijt manifesta cicatrix:/ Et nota, si coëant vulnera. dentis erit’. Translation from Van Thiel 1996, p. 200, note 67.

12 Liedtke 2017.

13 ‘O Haerlem! Ziet hier AMPSINGS wezen,/ Die syne STAD ons geeft to lezen;/ Een HARDER, trou voor Godes Kerk,/ En vaerdig in des Heeren werk;/ Wiens heyl’ge RYMEN en GEDICHTEN/ In wak’ren ernst de vromen frichten:/ Met recht van yder Haarlems kind,/ En van des Heeren volk bemind’. See also Van Thiel 1996, p. 199.

14 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 246, note 2: ‘O Haarlem, look upon Ampzing’s likeness / He who give us his city to read./ A shepherd, true to the church of God,/ And zealous in the work of the Lord./ Whose sacred verses and poetry / Uplift the pious with inspiring gravity./ Rightly is he beloved of all Haarlem’s children / and the Lord’s people’.

15 Liedtke 2017.