A4.3.51 - A4.3.55

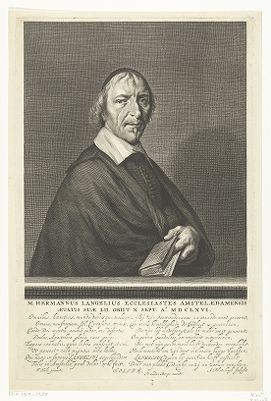

A4.3.51 Workshop of Frans Hals, possibly Frans Hals (II), Portrait of Herman Langelius, c. 1658-1660

Oil on canvas, 76.6 x 63.8 cm, monogrammed center right: FH

Amiens, Musée de Picardie, inv. no. M. P. Lav. 1894-95

In 1909, this portrait’s sitter was identified as Herman Langelius (1614-1666), on the basis of the engraving by Abraham Bloteling (1640-1690) [1].1 This devoted Amsterdam preacher had received particular attention through his condemnation of Joost van den Vondel’s (1587-1679) play Lucifer in 1654. As a result, the texts were confiscated, and the play was dropped after only two performances in the municipal theatre of Amsterdam. Vondel was the most important Dutch poet of the 17th century and an advocate of confessional tolerance. He was also critical towards the Calvinists, who dominated Holland at the time. Langelius was one of their most vociferous proponents. After his death in 1666, his portrait engraving was published bearing a text surpassing any other praise of the dead:

‘To all heretics, the world, waverers and sinners

He was everything, shipwreck or sea, guiding star or earthquake

In his heart, a devotee of God; in his soul, a ray of light; in his voice

A Paul in his eloquence, a rare glory to the apostolic flock.

A bachelor, he was married to his books, and a man to whom

His life was a labour devoted to propagating children for Heaven

Such – O, how sad to say! – was his likeness here on earth in Amsterdam’.2

What caused this person of authority, or the patrons commissioning his portrait, to turn to Haarlem instead of selecting one of the many excellent Amsterdam painters? The key might be in the engravings of preachers that were executed after Hals’s design, such as the Portrait of Johannes Bogaert (C2), the Portrait of Caspar Sibelius (C29), or the Portrait of Hendrick Swalmius (C34). The composition of the present portrait, with the sitter's turn towards the viewer, the lighting emphasizing only the head and the hand with the book, is typical for Hals. The structure of diagonals is strictly organized. Nevertheless, the painted surface that is visible today, displays no trace of Hals’s typical brushwork. Rather, short, and choppy brushstrokes dominate the highlighted edges as well as the shadowed areas. This restless appearance can only be explained by Hals designing the portrait’s basic outlines, while delegating the detailed completion to an assistant.

The finished picture seems to have been on display many years before Langelius’s death in 1666, and the engraving by Bloteling could have been created prior to his decease, since some prints have been preserved that do not feature the posthumous eulogy. In any case, the commission to Hals was the subject of a critical discussion, as documented in a poem published in 1660 by Herman Frederik Waterloos (1625-1664):

‘Why, old Hals, do you try and paint Langelius?

Your eyes are too dim for his learned lustre,

And your stiffened hand too crude and artless

To express the superhuman, peerless

mind of this man and teacher.

Haarlem may boast of your art and early masterpieces,

Our Amsterdam will now bear witness with me that you

Have perceived not half the essence of his light’.3

Indeed, the execution of the portrait is picture was hard; perhaps an execution by Hals’s own hand would have met with a more favorable judgment.

A4.3.51

© Collection du Musée de Picardie, Amiens; photographies Michel Bourguet/Musée de Picardie

1

Abraham Bloteling

Portrait of Herman Langelius (1614-1666), after c. 1658

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1907-2987

cat.no. C55

A4.3.52 Workshop of Frans Hals, possibly Frans Hals (II), Portrait of a seated man, c. 1660

Oil on canvas, 69.0 x 60.5 cm

Paris, Musée Jacquemart-André, inv.no. 427

This composition repeats the relaxed portrait pose with the arm over the back of the chair, which Hals used several times. However, in comparison to earlier examples, the present picture is characterized by a clumsy harshness. There is no detachment from the visually perceived subject, which would allow for a representation in loosely flowing brushstrokes, as part of a fleeting overall impression. The portrait is not built up out of a framework of diagonals, but expands into the foreground in an ungainly and heavy manner. There is no experience of any structure, which is so characteristic for the pictures of other sitters in this pose as can be observed, for example, in the area of the hands in the two male portraits in Washington (A1.114, A1.118). This approach is developed even further in the Portrait of a man with a slouch hat (A1.130), which was painted shortly after the present picture.4

Where the comparative examples demonstrate a dissolution of the visual impression in diagonally structured brushstrokes, at the same time maintaining a high degree of adherence to the three-dimensional shape of the face and to the anatomy of the hands, the present picture shows little of this delicate abstraction. Angular contours and hard light accents cut into the visual impression, without any connection to the facial features and their expression. This crude manner of painting is the work of a follower of Hals. In some respects, it shows a connection to other, late ‘Halsian’ works. For example: the folds of the sleeve bring to mind the Portrait of an unknown man in the Fitzwilliam Museum (A4.3.55), and the modelling of the face in Portrait of Herman Langelius (A4.3.51).

A4.3.52

Paris, Musée Jacquemart-André - Institut de France © Studio Sébert Photographes

A4.3.53 Workshop of Frans Hals, possibly Frans Hals (II), Portrait of a preacher, c. 1660-1662

Oil on panel, 35.5 x 29.5 cm, monogrammed lower right: FH

Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, inv.no. 2023.962 (on loan from The Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo Collection)

In this portrait, the face has been rendered with dots and dashes of the brush, rather than with swift, rhythmic brushstrokes. It lacks the characteristic accuracy which is so typical for late, autograph works by Hals, such as the small Portrait of a man in the Mauritshuis in The Hague (A1.131) and the heads of the Regents of the Old Men’s Almshouse (A3.62).5 In comparison, the direction of the gaze in the present painting is unclear, and the facial expression remains vague. Nevertheless, the compositional arrangement and the coloring are typical for Frans Hals. Accordingly, the initial composition and modelling were most likely done by the master. Subsequently, the portrait would have been fully finished by an assistant. The manner of this latter hand resembles sections in the Portrait of a man, possibly a clergyman (A3.60) and the Portrait of Cornelis Guldewagen (A4.3.54). Consequently, the painter can be assumed to be the same person, possibly Frans Hals (II) (1618-1669).

A4.3.53

A4.3.54 Workshop of Frans Hals, possibly Frans Hals (II), Portrait of Cornelis Guldewagen, c. 1660-1663

Oil on panel, 41.6 x 31.4 cm, inscribed lower left: AETAT SVAE / 60

Champaign, Krannert Art Museum, inv. no. 1953-1-1

Cornelis Guldewagen (1600/1602-1663) was the owner of the brewery ‘Vergulde Hart’ in Haarlem. He is known to have been a member of the town government for a number of years and served as mayor several times from 1642 onwards. He was also known as a gifted musician. Together with Johan de Wael (1594-1663) he had organized the replanting of 1300 expensive tulip bulbs from Wassenaer to Haarlem in early February 1637. It seems that they only flowered partially and lost their value in the sudden fall in tulip prices.6 His brother-in-law Andries van der Horn (1600-1677) and his wife Maria Pietersdr. Olycan (1607-1655) had been painted by Hals in 1638 (A1.93, A1.94).

Guldewagen’s painted portrait was only rediscovered in the 20th century, after a watercolor copy by Cornelis van Noorde (1731-95) had already been known in the earlier Hals literature [2]. The historical inscriptions on the copy and its pendant (D88), permitted the identification of the portrait of Guldewagen’s wife, Agatha van der Horn (1603-1680), by Jan de Braij (c. 1626/1627-1697) and dated 1663.7 The commission of the woman’s portrait to the smoother and more fashionable painter De Braij is a noticeable indication for a possible resistance in accepting late works by Hals. Nevertheless, the same-size panels were probably obtained at the same time. The compositions were most likely also determined for both portraits from the outset. In the final result, the man sits a little closer to the viewer edge, but his upper body is turned towards the companion piece.

The painterly style in the present portrait differs from that in the few late works which were executed by Hals himself. The composition and the first sketch may have been created by the master himself. However, the broad brushstrokes, with their hard edges, are certainly not by him. These were probably painted by the assistant who was also involved in the execution of the Portrait of Herman Langelius (A4.3.51) and the Portrait of a preacher (A4.3.53). The accuracy of the portrait can be assessed in comparison with Guldewagen’s portrait in the group portrait Officers and sub-alterns of the St. George civic guard of c. 1642, by Pieter Soutman (c. 1593/1601-1657) [3][4].

A4.3.54

2

Cornelis van Noorde

Portrait of Cornelis Guldewagen

Haarlem, Noord-Hollands Archief, inv./cat.nr. NL-HlmNHA_1100_33427

cat.no. D87

3

Detail of cat.no. A4.3.54

4

Detail of Pieter Soutman

Officers and sub-alterns of the St. George civic guard

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv.no. OS I-314

A4.3.54a Anonymous, Portrait of Cornelis Guldewagen

Oil on panel, 22.9 x 17.8 cm

Sale London (Christie’s), 23 November 1962, lot 83

Copy after the abovementioned Portrait of Cornelis Guldewagen. The entry in the sale catalogue notes that the panel has been cut on all sides and cradled, probably due to its bad condition.8

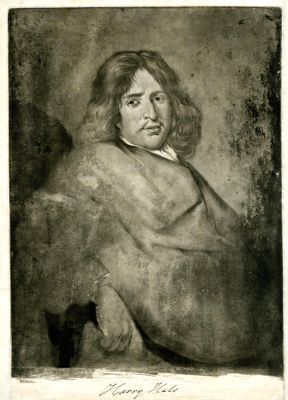

A4.3.55 Workshop of Frans Hals, possibly Frans Hals (II), Portrait of an unknown man, c. 1664-1666

Oil on canvas, 80 x 67 cm, monogrammed lower right: FH

Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, inv. no. 150

The wide-brimmed hat was revealed again during a restoration in 1949. As in a number of other Hals portraits, it had been overpainted at a later stage. The bare-headed sitter is visible still in a mezzotint by an anonymous engraver, created in England between 1770 and 1790 and inscribed Harry Hals, which shows a smoothed version of the boldly executed painting [5]. Groen and Hendriks found that the present portrait features the same groundlayer as the Portrait of a man with a slouch hat (A1.130).9

A4.3.55

5

Anonymous c. 1770-1790

Portrait of a man, c. 1770-1790

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1902,1011.7484

cat.no. C54

© The Trustees of the British Museum

A4.3.55a Anonymous, Portrait of an unknown man, c. 1750-1850

Oil on canvas, 33.5 x 26 cm

Stockholm, Hallwylska Museet, inv. no. XXXII:B.146.HWY

The collection catalogue characterizes this painting 'as a relatively weak copy of the signed portrait [in the Fitzwilliam Museum]'.10 In fact, the copy is a simplified version of the original portrait, omitting the right wrist and the hat – the latter was probably still overpainted at the time the copy was made.11

A4.3.55a

Motzkau, Holger, Hallwylska museet/SHM

Notes

1 Moes 1909, p. 68, 102, no. 51.

2 ‘Omnibus, haereticis, mundo dubusque, malisque,/ Omnia, naufragium, sal, Cynosura, tremor,/ Corde Dei mystes, anima jubar, ore disertus/ Paulus, Apostolico gloria rara gregi./ Expers connubii, quia libris nupserat, et cui,/ Ut pareret caelo pignora vita labos./ Qui nunc in superis LANGELIUS angelicus, idem/ Talis in Amstelio, proh dolor! Orbe fuit’. See also Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 352.

3 ‘Wat pooght ghy ouden Hals, Langhelius te maalen? / Uw ooghen zyn te zwak voor zyn gheleerde straale; / En uwe stramme handt te ruuw, en kunsteloos, / Om ’t bovenmenschelyk, en onweêrgaadeloos / Verstant van deeze man, en Leraar, uit te drukken. / Stoft Haarlem op uw kunst, en jonghe meesterstukken, / Ons Amsterdam zal nu met my ghetuighen, dat / Ghy ’t weezen van dit licht, niet hallef hebt ghevat’. H.W. Waterloos in Van Domselaar 1660, p. 408. See also: Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 352.

6 Goldgar 2007, p. 193.

7 Jan de Braij, Portrait of Agatha van der Horn, 1663, oil on panel, 41.5 x 32.5 cm, Luxembourg, Musée d’Art de la Ville de Luxembourg, inv.no. 51. See also chapter 3.5.

8 Slive 1970-1974, vol. 3, p. 108.

9 Washington/London/Haarlem 1989-1990, p. 127, plate VIII h and i.

10 Cassel-Phil/Engellau-Gullander 1997, no. 84.

11 Goodison 1949, p. 197-198.